Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Mar 30, 2021

US Treasury’s proposed SDR allocation

At a meeting of the G20 finance ministers on 26-27 February, US Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen said that the US supported a proposed USD500-billion allocation of the International Monetary Fund (IMF)'s reserve assets, known as Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), to all IMF members. If the US uses its veto power at the IMF to approve the allocation at the proposed level, then low-income countries' SDR holdings would increase threefold, providing sizeable balance of payments support during and in the wake of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. We consider the policy options available to implement a general allocation and examine the key implications for frontier and emerging markets.

US position is decisive

General SDR increases must be authorized by IMF members holding 85% of the total votes. Given that the US holds 16.5% of the total votes, the country's support is decisive as it alone has the capacity to veto the effort. Although the US Treasury has signaled support for a USD500-billion allocation, several House Democrats on 12 February tabled a new bill in the House of Representatives - alongside companion legislation reintroduced to the Senate two weeks previously - that supports a general allocation of 2 trillion in SDRs (equivalent to USD2.874 trillion) by the IMF. The bill is likely to be met with strong Republican opposition as they will argue that the allocation will benefit US adversaries such as Iran and Venezuela.

Who stands to benefit?

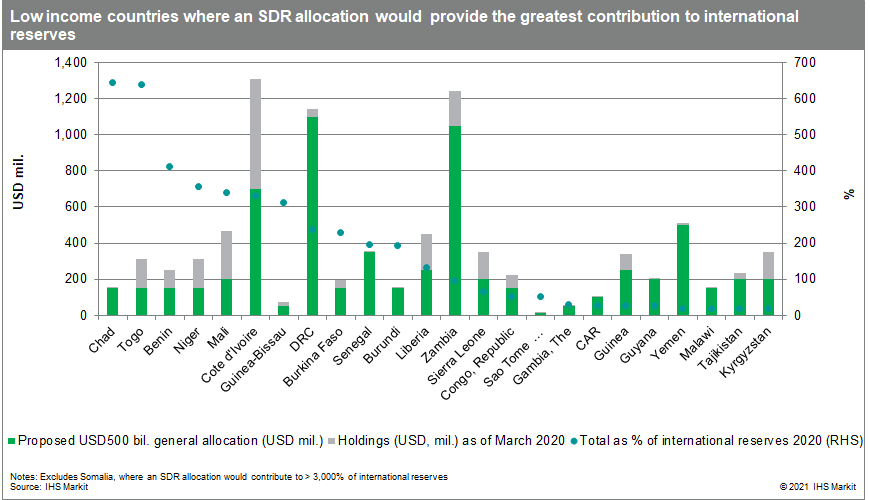

Unlike under traditional IMF programs, any new SDR allocation would be unconditional and need not be repaid by the beneficiary. However, SDRs must be redistributed according to the IMF's existing quotas, which are heavily skewed towards the wealthiest economies. As it stands, the largest beneficiaries of a general SDR allocation would be the United States, Canada, European countries, and the larger economies within Asia Pacific, notably mainland China. However, when quotas are adjusted for GDP, a general allocation would still make a sizeable contribution to lower-income countries, amounting to about 3.1% of GDP on average. As a freely exchangeable reserve asset, a general SDR allocation would significantly benefit countries with scarce international reserves or where additional buffers might be needed, such as in resource-dependent economies. This especially applies to sub-Saharan Africa, where new SDRs would amount to 201.3% of existing reserves on average. By contrast, already sizeable reserve buffers in the Middle East and North Africa, concentrated largely in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, suggest an SDR allocation would have a more limited effect.

Options for reallocating SDRs

Given the potentially inefficient distribution of SDRs under a general allocation, the US and other leading economies have proposed reallocating all or part of their additional SDRs to lower-income countries. If, for instance, the G20 agreed to reallocate 5% of its combined additional SDR holdings (at the USD500-billion level) according to existing country quotas, then the 60 low-income countries (in addition to non-low-income country Angola) included in our data set would obtain the equivalent of USD50.32 billion in additional SDRs for a total of USD69.43 billion including existing SDR holdings, or a little under USD1.14 billion on average in total for each low-income country. Any reallocation would almost certainly require the signing of multilateral agreements before a general SDR allocation is authorized, probably through a majority decision by the G20 nations, to ensure fair and equitable treatment and that there are no delays in the disbursement of funds.

Unintended consequences

The implementation of a general SDR allocation appears to be very likely and would provide sizeable benefits to low-income countries, despite the IMF already being well-capitalized. In any case, a general SDR allocation entails three notable drawbacks:

- A large SDR allocation may well undermine ongoing debt relief efforts that are also being coordinated through the G20. As SDR allocations are unconditional and need not be paid back, they could be exchanged for hard currency used to repay debts owed to private creditors that are currently not participating in either the G20's DSSI or the Common Framework for Debt Treatments.

- Unlike existing IMF programs, SDR allocations currently entail no monitoring or accountability on the use of proceeds, posing major bribery and corruption risks.

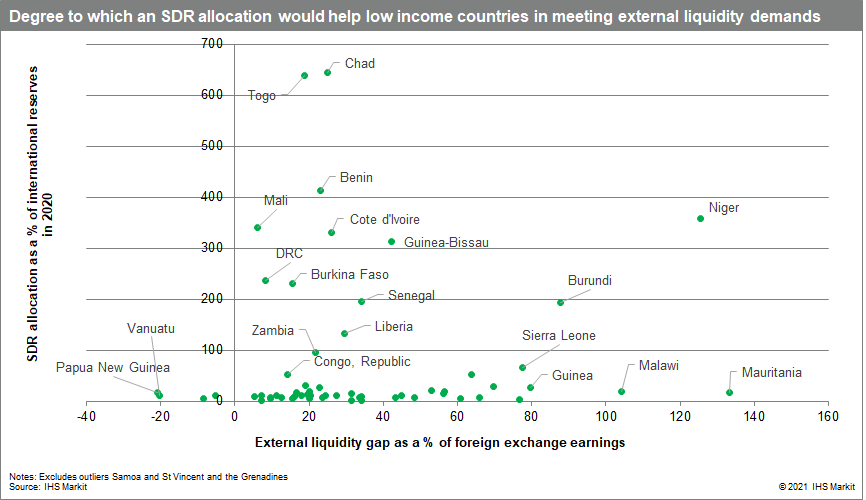

- The IMF's fixed system is based primarily on economic size and contributions to the Fund. Consequently, the distribution of SDRs, even within the group of low-income countries, does not correlate with those countries experiencing the greatest external liquidity pressures.

This blog post was written with contributions from Anton Casteleijn, Senior Economist; Archbold Macheka, Economist; John Raines, Associate Director; Petya Barzilska, Senior Research Analyst; and Brian Lawson, Economic and Financial Consultant

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-treasurys-proposed-sdr-allocation.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-treasurys-proposed-sdr-allocation.html&text=US+Treasury%e2%80%99s+proposed+SDR+allocation+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-treasurys-proposed-sdr-allocation.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=US Treasury’s proposed SDR allocation | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-treasurys-proposed-sdr-allocation.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=US+Treasury%e2%80%99s+proposed+SDR+allocation+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fus-treasurys-proposed-sdr-allocation.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}