Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Sep 01, 2022

Semiconductors and Chips: The 21st Century Arms Race

The United States Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) formally announced the banning of four major semiconductor technologies for export in mid-August. The technologies meet the criteria set out under Section 1758 of the Export Control Reform Act (ECRA) and are essential to the national security of the United States.

The four technologies are, two substrates of ultra-wide band gap semiconductors (Gallium Oxide and Diamond), Electronic Computer-Aided Design (ECAD) software specially designed for the development of integrated circuits with Gate-All Around Field-Effect Transistor (GAAFET) structures, and Pressure Gain Combustion (PGC) technology. All of the newly licensed technologies have a clear dual-use aspect with various commercial and military applications.

The export control of the above-mentioned technologies dovetails with the recent U.S. government CHIPS for America Act. The new act seeks to reassert 'American leadership in semiconductor manufacturing by increasing Federal incentives in order to enable advanced research and development, secure the supply chain, and ensure long-term national security and economic competitiveness.' One aspect of the CHIPS Act is to position American manufacturing into advanced 5 and 3 nanometre (nm) transistor processes, an area in which it currently lags behind major global firms in Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea. In order to retain global leadership via military and defence systems such as satellites, aircraft and missiles, a home-grown semiconductor supply chain is important.

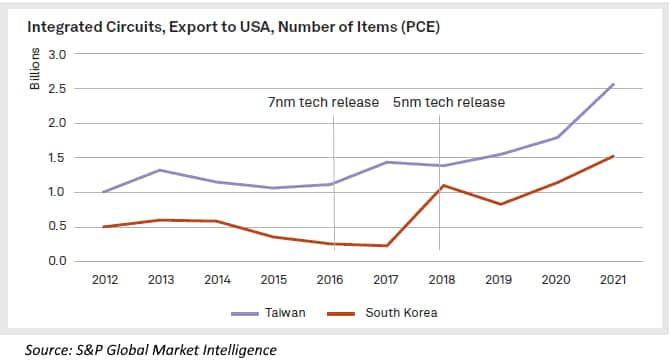

In this context, current American manufacturing is dependent on a number of countries for chips, semiconductors, and integrated circuits. The U.S. does not have the current capability to manufacture existing 7 nanometre and 5 nanometre chips, the trade data below highlights where the shortfall is sourced from. Today, corporations such as Taiwan's TSMC and South Korea's Samsung provide much of the chips for American commercial and military applications.

![]()

For each technological advance from the release of 7nm to 5nm technology, U.S. imports of chips and integrated circuits has grown. The potential for disruption to the delicate and stretched U.S. supply chain for semiconductor chips due to geopolitical issues in the context of Taiwan sovereignty and South China Sea access is high. The U.S. has a heavy reliance on a longstanding ally in Taiwan, a country that also falls under China's 'One Country Principle'. Recent political tensions involving the U.S. and China in relation to Taiwan may have a bearing on semiconductor supply chains in the future.

Equally, China is expanding its own home-grown semiconductor manufacturing but still lags slightly behind the U.S. The acquisition of major semiconductor machines by China with which to create chips and integrated circuits has increased over the last 10 years.

![]()

A majority of semiconductor making machines have been imported from Japan, the Netherlands, U.S, and South Korea to China. ASML, a Dutch company manufacturing lithography machines for the production of chips, is the only global firm that has the technology to produce Extreme Ultraviolet Lithographic (EUL) services which can manufacture chips at the more advanced 5 nanometre level. ASML has been in the spotlight recently as the U.S. has sought Dutch assistance in curbing the sale of semiconductor making machinery from ASML to China.

Analysts have noted though, that while ASML has the production technology for more advanced 5nm and 3nm chip manufacturing, China does not have the foundries or facilities to produce chips greater then 14nm or 7nm[1]. SMIC (Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp), China's biggest chip maker, has only just achieved the production of items at the 7nm level. The majority of Chinese imports of ASML technology has concentrated on Deep Ultraviolet Lithography (DUL) which is not as advanced as the EUL capability.

With the current technology in mind and its pace of change, there is a race to manage the semiconductor manufacturing process as it moves towards 3nm processes in 2023. The U.S. and China are developing internal, on-shoring facilities and investing heavily in the manufacturing of individual chips and foundries. Caught in the middle is the global supply chain, especially those managing export controls through the shipping, financing, or insuring of goods. The need to understand the semiconductor industry and the technological factors driving production and new export licencing requirements is becoming increasingly important.

[1]https://www.caixinglobal.com/2022-08-15/us-restrictions-on-chip-software-exports-could-bite-in-the-long-term-analysts-say-101926579.html

For more information visit Trade Compliance Secure, or subscribe to our complimentary Risk & Compliance quarterly newsletter for more insight.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsemiconductors-and-chips-the-21st-century-arms-race.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsemiconductors-and-chips-the-21st-century-arms-race.html&text=Semiconductors+and+Chips%3a+The+21st+Century+Arms+Race+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsemiconductors-and-chips-the-21st-century-arms-race.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Semiconductors and Chips: The 21st Century Arms Race | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsemiconductors-and-chips-the-21st-century-arms-race.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Semiconductors+and+Chips%3a+The+21st+Century+Arms+Race+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsemiconductors-and-chips-the-21st-century-arms-race.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}