Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Sep 01, 2022

Managing Dangerous Cargo Risk in the Era of Digitalisation

The safety of ships carrying dangerous goods has always been a concern for the shipping community. To improve the security and safety of such carriage, international conventions and individual countries/territories have constructed a series of laws and regulations in terms of ship structure, personnel requirements, mechanism establishment, emergency disposal, DG warehouse and port facilities, etc. The ISPS code (International Ship and Port Facility Security) by International Maritime Organisation (IMO) entered into force in 2004, as the basis for a comprehensive mandatory security regime for international shipping. The purpose of the security measures is to prevent and obstruct security-related incidents that may damage the ports, the port facilities or the ships that call in to such ports.

Such industry regulation highlights the importance of identifying potential risks and where possible, mitigating mishandling risk proactively. One possible way is by harnessing the value of big data with relevant data sets. For example, maritime and international trade datasets allow analysts to identify patterns of dangerous cargo and typical related commodities, the trade routes and locations involved, and the vessels and facility compliance status. In addition, logistics visibility may help track real-time shipment statuses to prepare in advance and prompt on-time data filing, while also aiding risk alerts and better operational efficiency.

In this article, we explore characteristics relevant to dangerous cargo and how maritime and trade data can help industry stakeholders assess and mitigate risks inherent to dangerous goods shipping.

Identify Typical Dangerous Goods

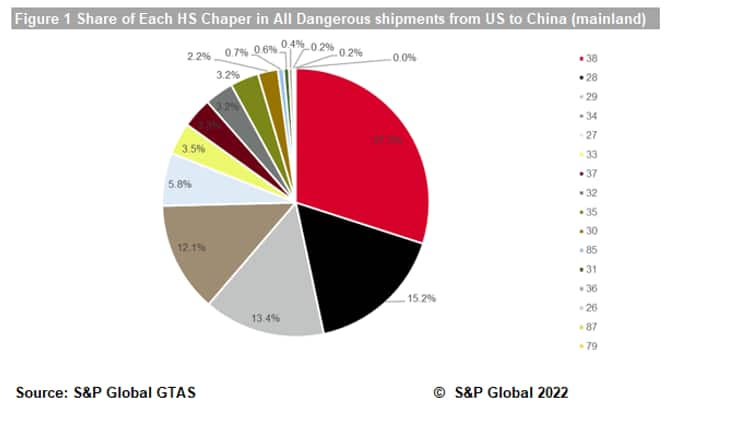

Referencing international trade data by Global Trade Analytics Suite (GTAS), U.S. waterborne export shipments to mainland China YTD through August 2022 flagged as hazardous 'dangerous goods' (DG) are relatively concentrated at certain HS2 chapters. Chemical products (including organic, inorganic and miscellaneous) is the largest broad category across three HS chapters (HS 38, 28 and 29), accounting for 27%,15%, and 13.4% respectively, of all DG-marked shipments, followed by petrochemical-related or derivatives such as soaps and essential oils.

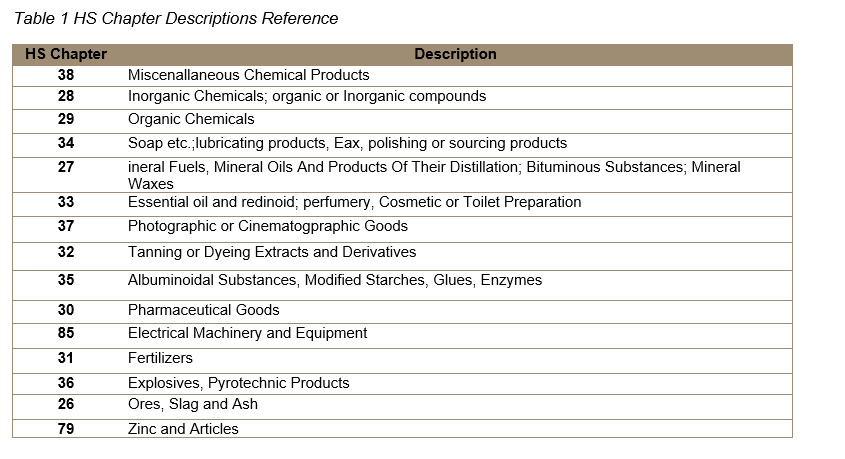

(HS Chapter Descriptions see Table 1)

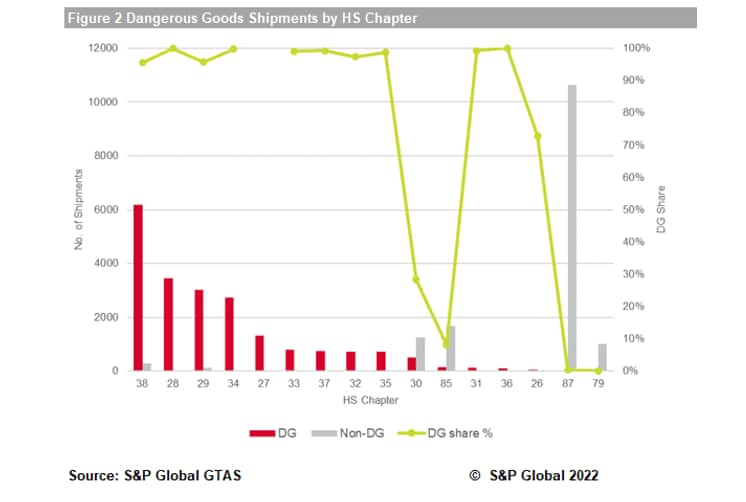

To validate another way that these commodities do feature 'dangerous goods', a reverse analysis on DG percentage in individual commodities' total shipments shows that nearly all of the chemical-related commodities are marked with a Dangerous Goods flag (95% - 99%), indicating strong consistency in HS mapping to DG.

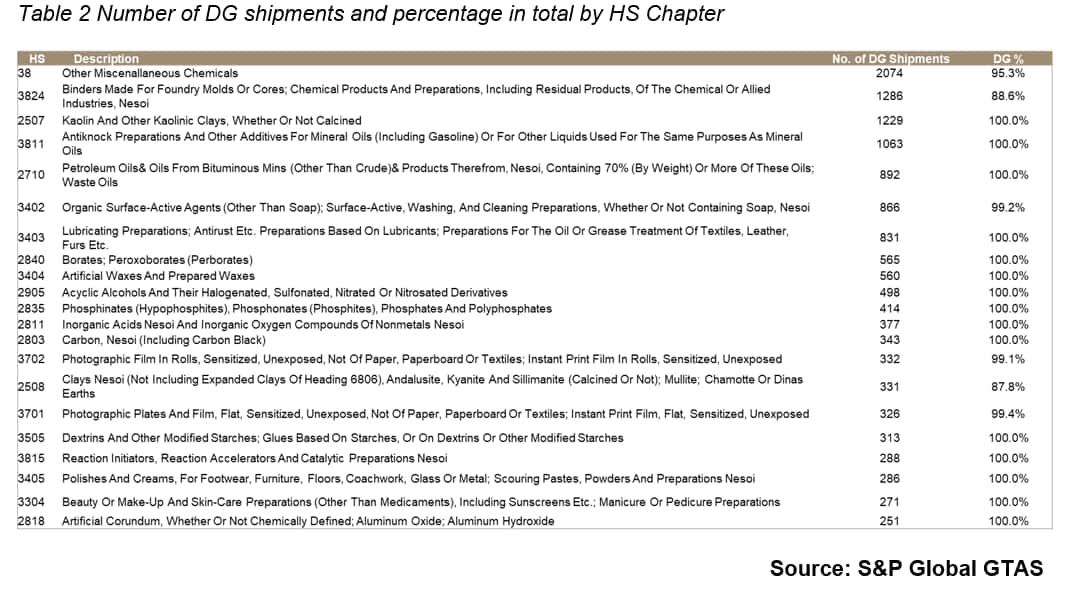

While spotting these HS Codes at 2-digit Chapter level is relatively straightforward and it might be obvious in the general view, when comes to practical risk identification method, the 2-digit HS code level could be too broad and may result in false positives. Therefore, for operational risk management, breaking further down into 4-digit HS code level or even lower could more accurate. In doing so, we found a list of items, mostly commodities related to chemicals, clays, petroleum and cosmetics, among those with most DG shipments. As the below table shows, almost all of these top 20 commodities should be shipped with the DG flag.

Locations of Export and Import

Another possible strategy is to 'advance monitor' by identifying the origination location of such DG shipments.

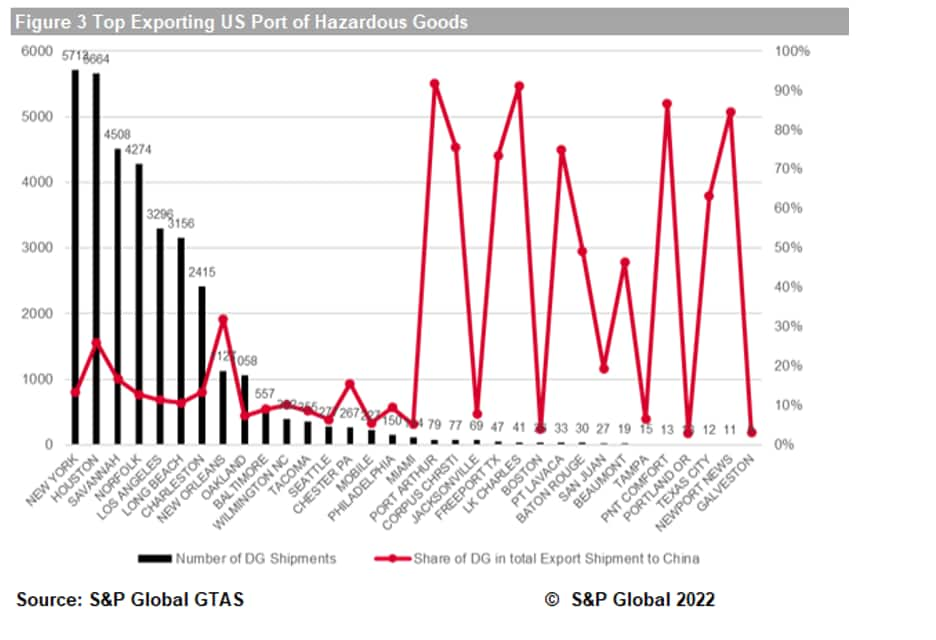

Though the U.S. has over 300 ports, export records destined for mainland China in 2022 shows that only around 30 ports had shipped out DG. When looking closer at those with the most frequent loadings, New York ranked first place in the list with 5,713 DG shipments in 2022 loaded, representing 13.3% of all NY-departed cargo. Although Houston ranked 2nd in shipment counts at 5,664, the percentage of its total loaded cargo is higher at 25.96%.

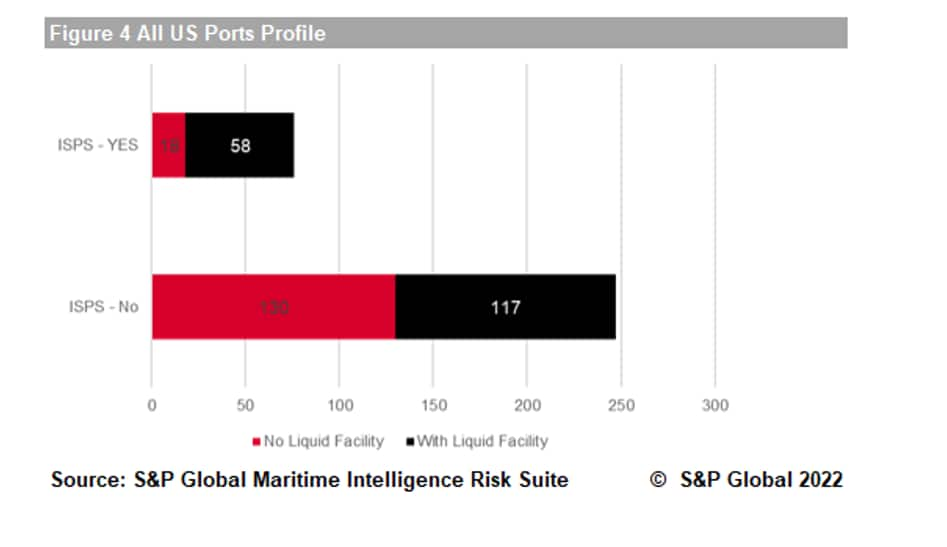

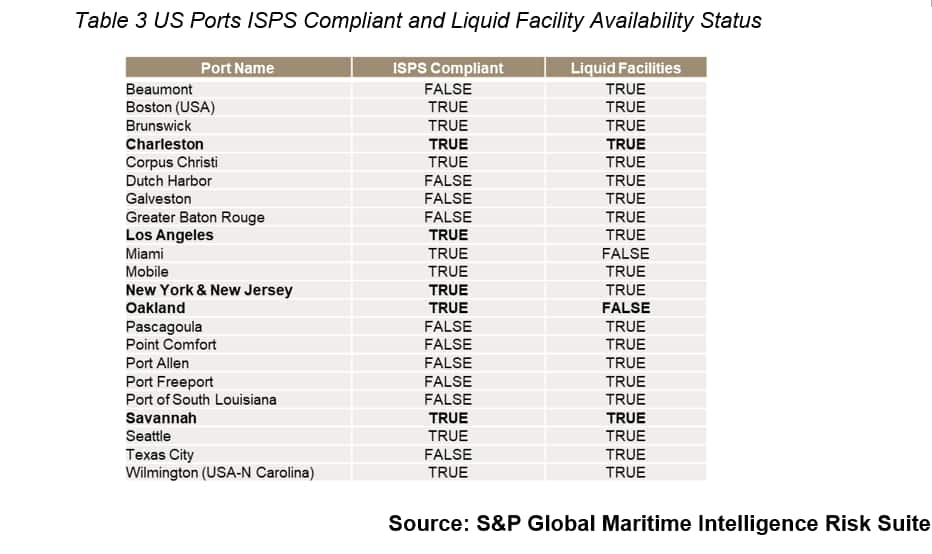

Port profiles also facilitate such understanding. Revealed by analysis of port data within S&P Global's Maritime Intelligence Risk Suite (MIRS), there are around 76 U.S. ports (including sub-ports) that are ISPS compliant; those with frequent DG shipments loaded are among them.

Country-Specific Reporting Requirements

China Customs recently reinstated the requirement of advance filing of electronic manifest data for imported dangerous goods. The requirement covers both the timing and the data elements to be submitted. Specifically for maritime trade, cargo imported on container ships shall be filed 24 hours prior to cargo loaded at the origination port; in the case of transhipment, it should be 24 hours prior to the loading at the last transhipment place. For non-container ships, the timing is 24 hours before arriving at the first domestic port.

Actually, this is not a new requirement. With the introducing of electronic filing system and digitalised data exchange, many other major authorities globally have enforced similar if not same advanced reporting rules for imported cargo and vessels. Various countries require the submission of detailed cargo information prior to vessel sailing (24-hour security initiatives) and/or prior to arrival at destination to local customs and port authorities. For example, EU Regulation 1875/2006 -Advance Manifest requires the lodgement of Entry Summary Declarations (ENS) for inbound cargo effective December 31, 2010. For deep-sea containerized shipments, i.e. from Americas or Asia to the EU, the ENS must be lodged at least 24 hours prior to commencement of loading in each non-EU load port. This is also essential for other advanced manifest systems e.g., AMS (USA), ACI (Canada) or MX-SAT (Mexico).

Types of ships with DG on board

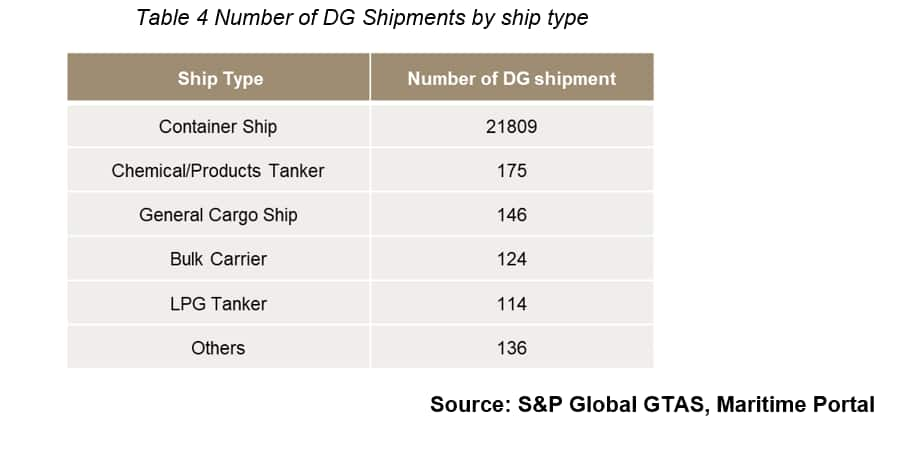

The advance reporting requirements by China Customs have differentiated containership and non-containership in terms of submitting data timing and spec. Yet for the EU, the differentiation is more depending on the cargo rather than ship type as 'No matter whether container, including reefer container, are shipped on container or bulk vessels, the deadline for transmitting ENS for containerized cargo is 24 hours prior to loading. Not the vessel type is important but whether the cargo is containerized or in bulk.' (According to carriers' DG shipping notification.)

For both authorities, it seems a focus is put on containerised trade. From a fleet analysis practical standpoint, this could be the reason why the requirements have specifically addressed the containerised trade reporting formality by regulations.

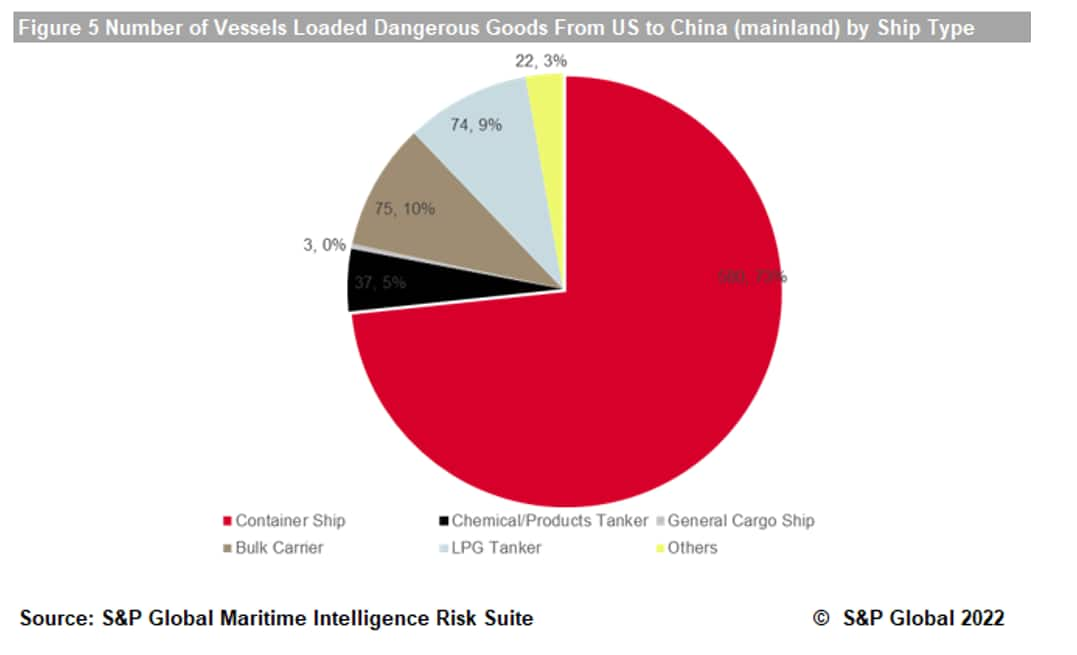

Containerships do carry a dominant share of DG when counted in shipments (~96.9%). Other ship types are unsurprisingly chemical/product tanker, general cargo ships, bulk carrier, LPG, as well as tanker if we consider the DG commodities to include petroleum and chemical products.

Nevertheless, from the marine safety perspective, the number of vessels calling with dangerous goods on board is still of concern. The percentage by vessels, bulkers and tankers exhibit a higher prevalence of DG voyages compared to the percentage of raw shipment counts.

Yet there could be other reasons for the differences. For example, container vessels usually carry shipments from multiple shippers and with numerous consignees, while bulk are more straightforward in terms of shipper-consignee-operator identification. Another reason for such complexity is, unlike bulk shipping, container ships consistently make multiple port calls all along the service string, and in many cases will involve transhipment, resulting in more challenges in identifying chains of custody.

Shipping Route: Direct or Transhipment

Transhipment is a quite normal and frequent practice, referring to vessels loaded with cargo from a particular loading terminal, which may not necessarily be the original country of origin. Therefore, the reporting requirements have highlighted the importance of chain-of-custody tracking for transshipment cargo.

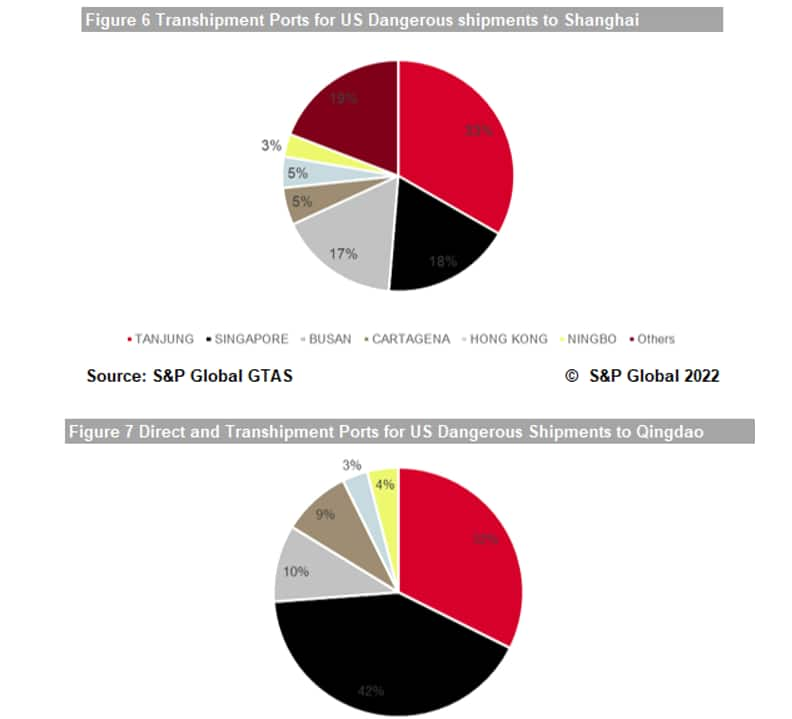

This highlights the importance of transhipment location and time visibility. Yet for different destination ports, the connectivity of transportation network would result in a pattern still depending on the location and transport mode of journey that could vary significantly by individual port pairs. For example, DG cargo shipping from U.S. to Shanghai is predominantly via direct shipping; less than 1% of shipments are conducted via transhipment, which are transhipped via Tanjung, Singapore, Busan etc. Conversely, direct shipping only accounts for 1/3 of total DG shipments from U.S. to Qingdao; Bremerhaven and Antwerp were the most frequent transhipment locations for that route.

Therefore, analysing the complete journey, and verifying with multi-angle data could be useful in comprehensive awareness.

Implication

The business community involved in dangerous goods shipping have reason to be concerned with the risks inherent in the physical movements of dangerous goods: ocean carriers, warehouse services, inland transportation, as well as financial institutions like insurance and trade finance providers facilitating such trades. Even the shippers and consignees who are not themselves involved in DG trade may be impacted by any accidental outbreak on board ships carrying dangerous goods. News reports appear quite frequently regarding goods like lithium batteries combusting during ocean journey (For example, the vessel, Felicity Ace, carrying about 4,000 vehicles including Porsches, Audis and Bentleys, some electric with lithium-ion batteries, caught fire in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean in February 2022). and improper handling of chemicals at port storage areas causing severe accidents and damage (such as incident of a chemical cargo ship near Sri Lanka as reported in https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/disaster-feared-chemical-cargo-ship-sinks-off-sri-lanka-2021-06-02/ ). Even when transportation methods themselves are compliant, operations personnel should remain cautious, enabled in part by a clear and accurate understanding of the cargo characteristics.

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter and stay up-to-date with our latest analytics

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmanaging-dangerous-cargo-risk-in-the-era-of-digitalisation.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmanaging-dangerous-cargo-risk-in-the-era-of-digitalisation.html&text=Managing+Dangerous+Cargo+Risk+in+the+Era+of+Digitalisation+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmanaging-dangerous-cargo-risk-in-the-era-of-digitalisation.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Managing Dangerous Cargo Risk in the Era of Digitalisation | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmanaging-dangerous-cargo-risk-in-the-era-of-digitalisation.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Managing+Dangerous+Cargo+Risk+in+the+Era+of+Digitalisation+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmanaging-dangerous-cargo-risk-in-the-era-of-digitalisation.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}