Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

May 18, 2022

Regime shift: Is higher inflation here to stay?

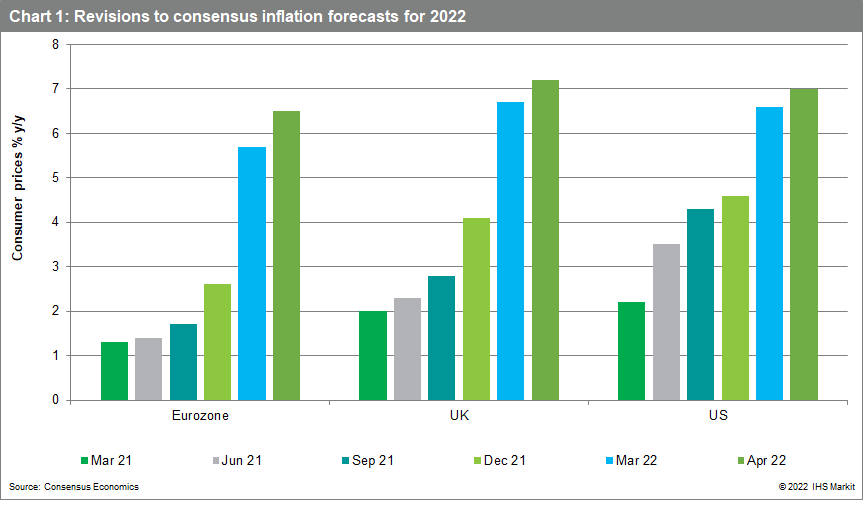

What was initially expected to be a transitory period of moderately higher consumer price inflation across the globe has morphed into a phase of persistent, exceptionally high inflation rates, captured in the evolution of annual forecasts for 2022. Upward pressures stemming initially from a range of primarily coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related effects are now being aggravated by various spillover effects following Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Focusing on Europe, we assess various arguments for and against such a shift.

- What was viewed initially by central banks as a transitory pick-up in inflation has turned into something much more worrisome.

- Eurozone inflation is likely to be persistently higher in future than during the pre-pandemic years.

- This reflects a range of influences, some global and some local.

- A scenario of unmoored inflation expectations and wage-price spirals is less probable, though the risks need close monitoring, particularly in other parts of Europe.

The case for

Various factors suggest that inflation rates will be higher in future than those we became used to in the decades prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. These include:

- Waning effects of global disinflationary forces.

- Over-stimulative policy and constraints on tightening.

- Rising inflation expectations.

- Climate change and energy transition.

Waning global forces

A confluence of factors contributed to sustained disinflationary forces across the global economy from the late 1980s and early 1990s. These included the decline of communism in eastern Europe, the EU's expansion and abolition of trade barriers, and China's accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO). Accompanied by exceptional increases in global investment and trade, facilitated in part by major advances in supply chain management and shipping, the result was a huge increase in the pool of global labour and sustained low costs of production.

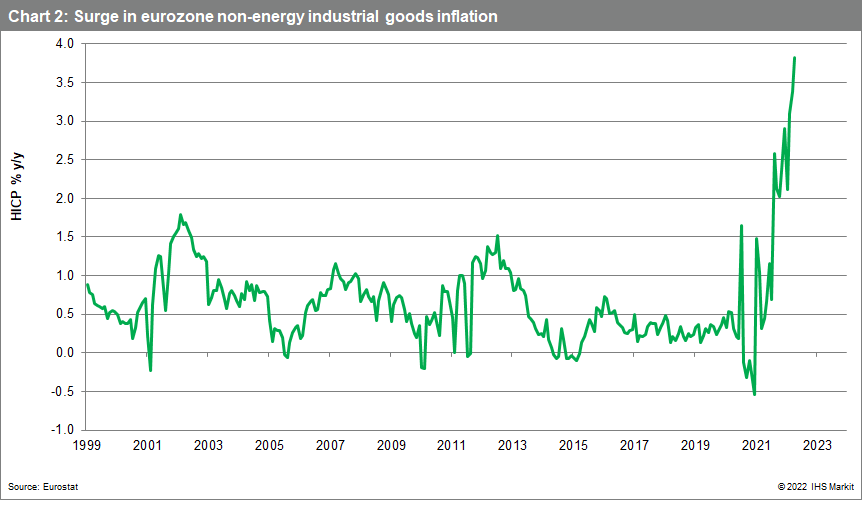

While extreme events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia's invasion of Ukraine have been fundamental to the short-term surge in goods inflation rates, they are also likely to reinforce the longer-term trend away from many of the disinflationary forces which held it down in the past. Global trade as a share of GDP peaked back in 2008 and more recently, the "trade wars" from 2018 and the subsequent extreme disruptions caused by the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict suggest security of supply chains is likely to take priority over competitive pricing for key products. The attraction of outsourcing is also diminishing for various reasons.

Expectations and policy

If a central bank is credible in its commitment to maintaining price stability, longer-term inflation expectations should remain well anchored, preventing wage and price-setting behaviour being subject to inflationary fears.

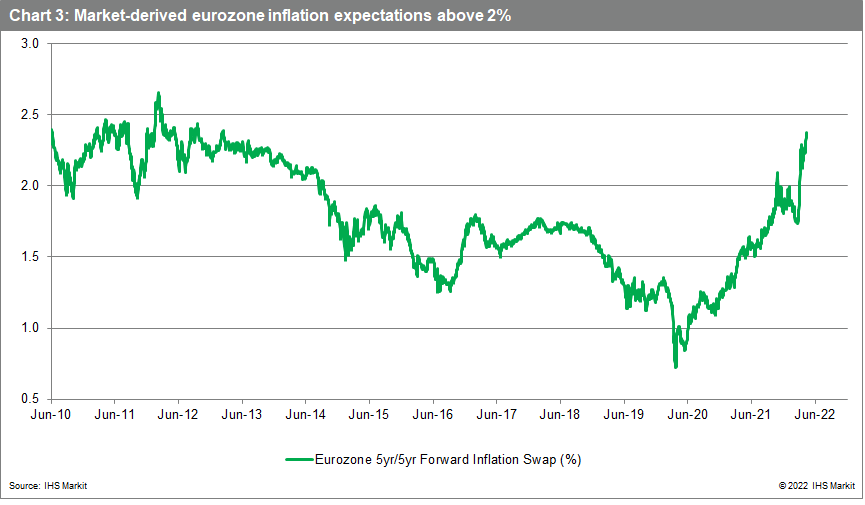

However, there have been signs recently that inflation expectations might be becoming less well anchored and there may be constraints (e.g., political pressures, recession risks, declining asset prices) on how far central banks are willing to go to keep them in check.

While the recent pick-up has been most apparent in shorter-term, consumer-based measures of inflation expectations, this is still relevant as they can influence wage bargaining. While the signals from longer-term inflation expectations have been more comforting, there too some warning signs are flashing. Although surveys of forecasters' expectations appear well anchored still, they typically do not deviate far from central bank inflation targets. In contrast, market-derived measures have picked up markedly since 2020 in some cases, though the trends are not uniform.

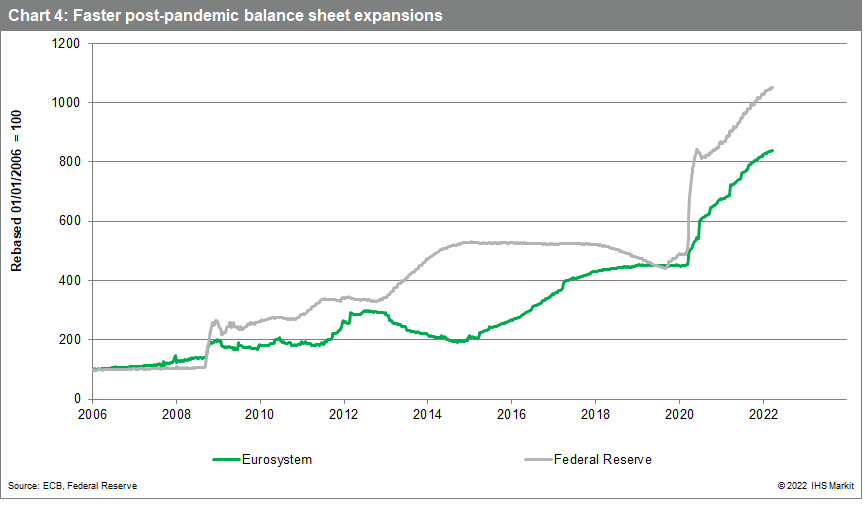

The differences in policy responses and economic recoveries following the GFC and COVID-19 pandemic are striking. The unprecedented magnitude of the contractions in activity during the initial phase of the latter in spring 2020, and the fiscal space provided by the exceptionally rapid and substantial QE by major central banks - including the ECB - led to very different fiscal responses and economic outcomes. Initial fears of another Great Depression, leaving permanent scars, proved to be way too pessimistic.

The recession was exceptionally deep but also unusually short. When the COVID-19-related constraints eased, output rebounded unusually rapidly. Since the rebound, policy has remained exceptionally stimulatory, including fiscally, supporting demand during a period when supply has responded unusually slowly due to various impediments.

Climate change

The various channels through which climate change could generate higher future inflation rates include:

- Global warming is associated with a greater incidence of damaging climatic events which may impact specific prices, notably for food.

- The transition to a net zero carbon emission world implies sharp increases in the price of carbon, in turn affecting consumer prices directly through higher energy prices, and indirectly through increased costs of production.

- Higher prices for the commodities essential to the deployment of "green technologies".

The case against

- The counter arguments against a regime change for inflation include:

- Rebalancing of supply and demand.

- Regime changes require multiple shocks.

- Technological factors, including e-commerce and automation.

- Labour market reforms and competitiveness challenges.

Rebalancing

Unlike in the aftermath of the GFC, supply has been unusually unresponsive to higher demand during the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, aggravated recently by the Russia-Ukraine conflict. This is apparent in various indicators, including extremely long suppliers' delivery times (evident in our PMI data), soaring transport costs, including for shipping, and shortages of key inputs to production.

Over time, some of these supply problems will ease. Either because supply adapts, the constraints due to the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict diminish, or demand weakens. Regarding the latter, household real incomes will be hit exceptionally hard in 2022 by soaring inflation, with the deterioration in household purchasing power potentially leading to lower underlying inflation.

Multiple shocks required

Looking back at historical experiences, once a low-inflation regime has become well established, a switch to a high-inflation regime generally requires a combination of shocks to occur. In the eurozone specifically, it would be difficult to argue against a low-inflation regime having been well established prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The caveat with this argument, however, is that the type of shocks historically required for a shift into a higher-inflation regime are precisely those which we are experiencing now, including excessively expansionary monetary and fiscal policies, as highlighted above.

Technological factors, including e-commerce and automation

The rise in digital technology and e-commerce has not only lowered costs but also kept a lid on inflation by allowing consumers to comparison shop, with the resulting price transparency increasing competition and curtailing businesses' pricing power.

Technological advances which enable machines to perform a wider range of tasks also hold down production costs. The use of artificial intelligence (AI) is still in its relatively early stages and is yet to spread to most of the economy, reflected in the relatively low use of robots compared to the numbers of people employed.

Labor market reforms and internal devaluations

One notable feature of the low-flation environment in the eurozone from the mid-2000s was member states copying many aspects of the labour reforms introduced in Germany. In short, pursuing wage moderation in order to improve competitiveness, preserving employment.

With the option of nominal exchange rate devaluations no longer available to eurozone member states, competitiveness improvements have to be achieved the hard way, via "internal" devaluations: i.e., through adjustments in relative unit labour costs, either via higher productivity or more commonly, though wage moderation.

The picture is not uniform across Europe, however. The UK in particular looks vulnerable to "second round" effects on inflation given persistently higher inflation expectations and reduced labor supply, related to Brexit, along with parts of emerging Europe, though the huge inflows of migrants from Ukraine could help to alleviate the risks from labor shortages in the latter.

Bottom line

There are persuasive arguments for and against a shift to a new regime of persistently higher inflation rates in Europe. We need to distinguish, however, between a new regime where inflation is higher than in the pre-pandemic period but remains around the central bank's target rate and one in which inflation expectations become unmoored and a wage-price spiral could follow.

In the eurozone, we believe the former is the more likely, reflected in our forecasts. The risk of the second outcome looks comparatively low in the eurozone for various reasons, including the long period of persistently low inflation prior to the COVID-19 shock. Still, we need to monitor the risks closely, particularly in countries where the potential for wage-price spirals looks more worrisome.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fregime-shift-is-higher-inflation-here-to-stay.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fregime-shift-is-higher-inflation-here-to-stay.html&text=Regime+shift%3a+Is+higher+inflation+here+to+stay%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fregime-shift-is-higher-inflation-here-to-stay.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Regime shift: Is higher inflation here to stay? | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fregime-shift-is-higher-inflation-here-to-stay.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Regime+shift%3a+Is+higher+inflation+here+to+stay%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fregime-shift-is-higher-inflation-here-to-stay.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}