Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jun 03, 2021

Mind the gap: The inflation outlook depends on it.

In many parts of the world, demand is growing faster than supply as vaccination rollouts continue and restrictions on gathering and travel are lifted. This is especially true in North America and some emerging regions such as Central and Eastern Europe. In these economies, the pace of price increases has accelerated, leading to heightened concerns about inflation. Mainland China is the one major exception, where robust growth has been supply-led. Thus, despite a strong post-COVID-19 rebound in the Chinese economy, inflationary pressures are muted.

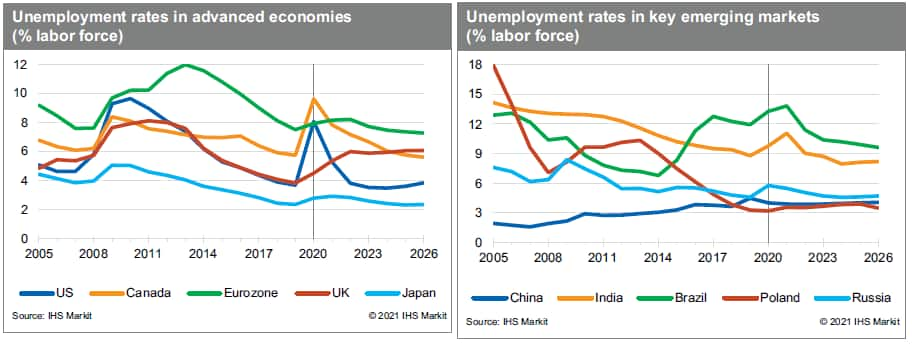

Even in the economies where the output gap is closing rapidly, labor force participation rates remain below pre-pandemic levels, meaning there is scope for more labor supply growth, which could ease the current labor crunch. Moreover, there is the possibility that labor productivity growth will increase during the post-pandemic recovery. Both of these trends could increase growth in potential GDP and slow the narrowing of the output gaps. The larger the output gap and the greater the slack in labor markets, the more room the economy has to expand before it hits capacity constraints, which in turn will crank up the pressure on price and wage inflation.

While inflation is rising and will continue to rise over the coming year, in most parts of the world, this increase will likely be temporary. The post-pandemic spurt in demand growth will slow, even as output gaps are closing. The removal of stimulus is a key factor behind our predictions of slowing GDP growth in 2022 and 2023. Moreover, we anticipate that supply (notably in labor markets) will respond to strong demand, mitigating some of the price (and wage) pressures.

Inflation Outlook: United States

The US economy will be one of a handful to close the output gap rapidly in 2021 and 2022. In 2021, real GDP growth (at 6.7%) will be the most rapid in the developed world. Growth in 2022 (4.7%) will remain well above trend, before returning to trend in 2023 and beyond. All this means that real GDP will surpass its previous peak in the current quarter and that the output gap will be closed by mid-2022. The previous peak in employment is also expected to be regained by mid-2022, with the unemployment rate falling to 3.5% by mid-2023. Not surprisingly, inflationary pressures are picking up and there is a fierce debate going on about how "transitory" this inflation spurt will be.

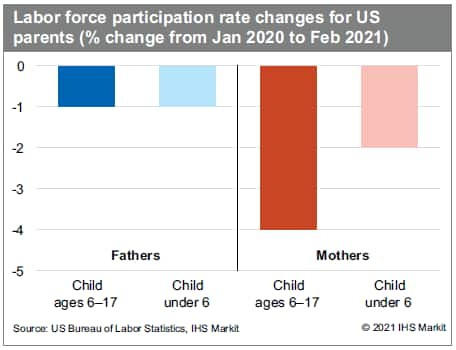

The intensity of the US debate about inflation points to the considerable uncertainty around estimates of potential GDP and its key components: productivity and the labor force. The civilian labor force participation rate has been declining gradually for the past two decades from around 67% in 2001 to a little over 63% right before the pandemic. It then plunged to nearly 60% in the spring of 2020 but has since recovered—it reached 61.7% in April. The plunge in the participation rate was especially pronounced for some demographic groups.

The participation rate for mothers with small children is still around 3.5% lower than in January 2020—a larger gap than men with small kids, and both men and women with no young kids. There has also been a sharp increase in the past year (around 3 million) in the number of people 65 years and older (with no disabilities) who are no longer in the labor force. There is potentially also a mismatch of skills and jobs, which explains (in part) why job openings are at record levels, while employment also remains well below the pre-pandemic peak.

While in April the official unemployment rate was 6.1%, one alternative measure, favored by US Fed Chair Jerome Powell, suggests that the unemployment rate was around 9%. All this implies that the US economy probably has "more room to run" and that the continued recovery in the labor force participation rate will help to keep inflationary pressures in check. IHS Markit analysts expect that temporary pressures will push US core inflation significantly above 2% in 2021, after which inflation will subside to near 2%.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmind-the-gap-the-inflation-outlook-depends-on-it.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmind-the-gap-the-inflation-outlook-depends-on-it.html&text=Mind+the+gap%3a+The+inflation+outlook+depends+on+it.+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmind-the-gap-the-inflation-outlook-depends-on-it.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Mind the gap: The inflation outlook depends on it. | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmind-the-gap-the-inflation-outlook-depends-on-it.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Mind+the+gap%3a+The+inflation+outlook+depends+on+it.+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fmind-the-gap-the-inflation-outlook-depends-on-it.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}