Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Mar 16, 2021

The geopolitical implications of vaccine rollout programs across MENA

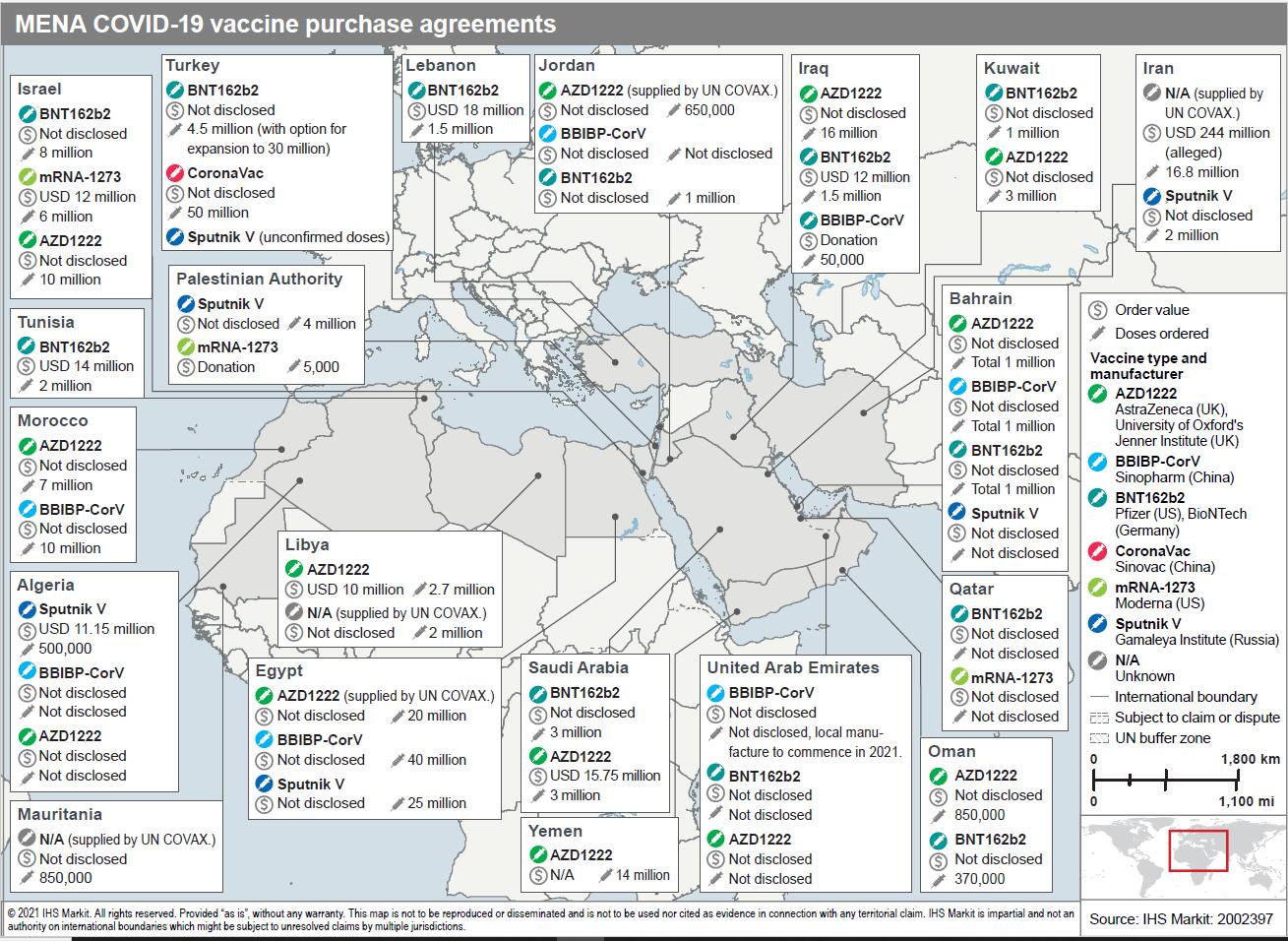

IHS Markit assesses that total real GDP in the MENA region contracted by 6.6% in 2020, and although we expect overall GDP growth to return in 2021, the growth is likely to be highly uneven across the region. Only smaller, wealthier MENA states have secured sufficient quantities of COVID-19 vaccine through advance purchase agreements (APAs) to provide total coverage of their populations in their vaccination programs (Israel, Qatar, and Kuwait have announced APAs to cover 130%, 100%, and 67% of their respective populations). Larger states such as Egypt and Turkey will also most likely eventually rely on local manufacturing, either of a domestic vaccine or via licensing arrangements, to build on their APAs.

These trends, effectively, will see MENA states divide into three tiers according to the success of their vaccination programs. A first tier of smaller, wealthier countries with centralized governments, such as Israel and states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (except Saudi Arabia), will likely be able to vaccinate most, if not all, of their populations and largely lift restrictions on their economies, particularly on the hospitality and tourism sectors and international travel, by the end of 2021. This is most likely to be a priority for those states where tourism and international travel represent significant proportions of the economy.

Economic reopening will be highly dependent on sufficient access to large enough quantities of vaccines. IHS Markit expects that, in many cases, states in this tier will secure vaccine supplies by both paying high premiums to pharmaceutical companies, as well as governments agreeing to share inoculation data with vaccine manufacturers - aiding global rollout strategies and increasing the efficiency of future research and development.

A second tier of vaccine states - Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Morocco, Tunisia, and Turkey - is likely to be held back in implementing a rapid vaccine rollout and a more rapid subsequent economic recovery because of having much larger populations than first-tier countries and the logistical difficulties of securing sufficient quantities of vaccine, infrastructure weaknesses, and political instability preventing or obstructing distribution. Such second-tier states without highly centralized and efficient healthcare systems are more likely to opt for limited vaccination programs with the intention of inoculating the most-vulnerable, old and sick demographics, avoiding further lockdowns and insisting that the majority of the younger population is able to continue to work, with or without vaccination. This will likely mean that localized containment measures, including curfews and limited opening hours for retail, are likely to be in place until late 2021-22, impeding a return to rapid economic recovery, but avoiding full shutdowns across sectors that are major employers, such as the manufacturing, textile, and agricultural sectors.

A final tier of countries will include those most weakened by the impact of sustained political instability, extremely low governance capacities, civil violence, and international sanctions, comprising Iraq, Lebanon, Libya, Syria, and Yemen. In these states, vaccine rollouts to any significant extent are unlikely to take place until well into 2022-23. It is likely that access to vaccines will be impeded by financing difficulties and the administration of any vaccination programs will be hampered by minimal infrastructure and the threat of ongoing violence, including for any international aid organizations.

All MENA states likely to be highly dependent on securing access to external sources of vaccine until at least second half of 2021, before domestic manufacturing is achievable

Only a few MENA states have been involved in vaccine research and development (R&D) and, although a wider group of states potentially has domestic manufacturing capabilities at the start of 2021, MENA countries remain heavily reliant on external vaccine suppliers. In response, MENA countries have become open to accessing COVID-19 vaccines from diverse sources to balance the risk of supply shortages and delays. For instance, Chinese pharmaceutical companies have established a footprint in the MENA region through offering clinical trials of vaccines in exchange for advance or expedited access to vaccines. Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey are all participating in vaccine trials of products developed by Chinese pharmaceutical companies Sinopharm, Sinovac, and CanSino. This is likely to facilitate the further expansion of Chinese vaccine programs in MENA in the two- to three-year outlook. In addition, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) permitted domestic clinical trials to be conducted of the Russian Sputnik V vaccine.

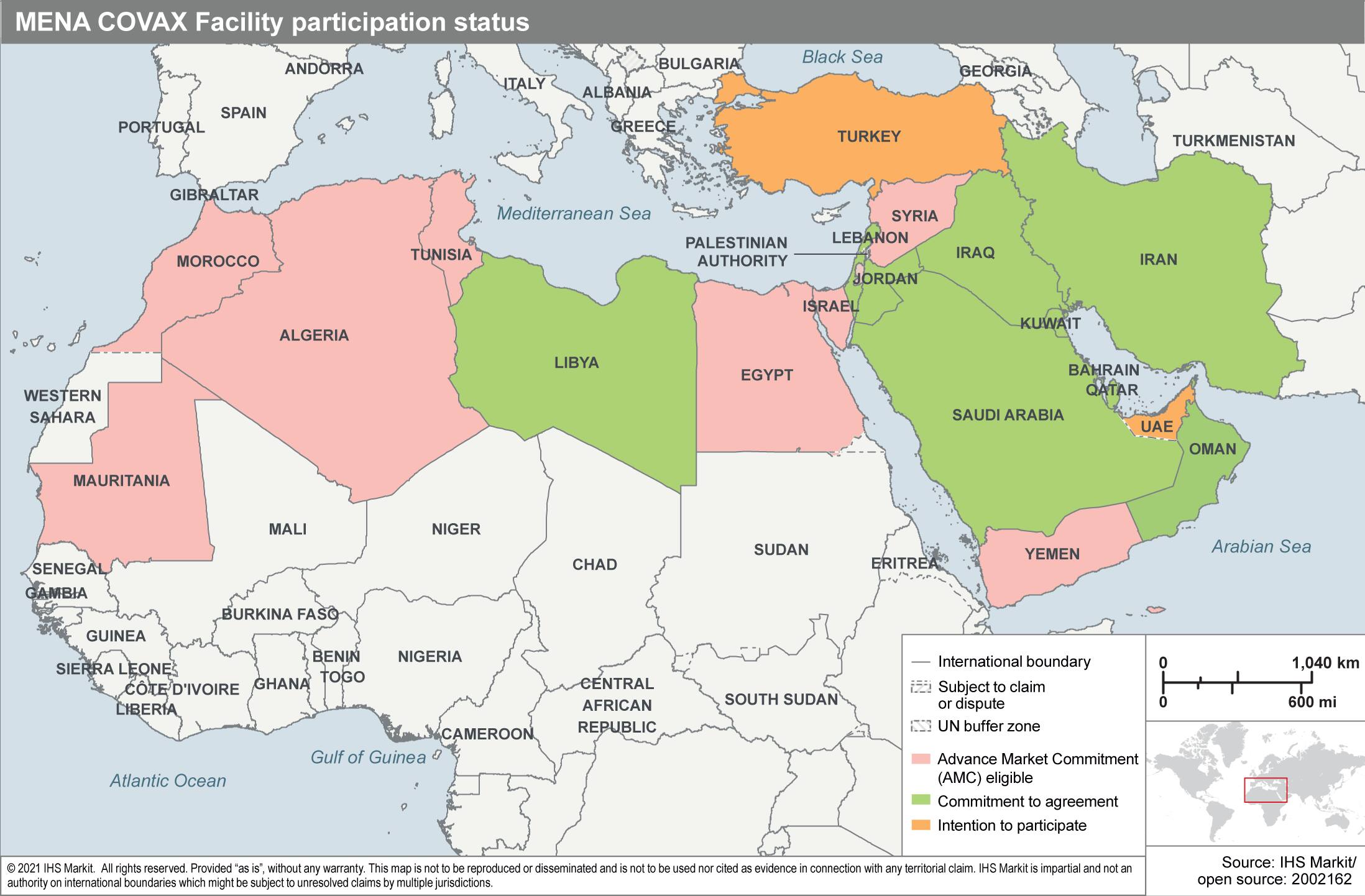

All the MENA states also signed up to participate in the World Health Organization's COVID-19 Vaccine Access (COVAX) Facility, which is intended as a multilateral body to pool resources for vaccine procurement and subsequent distribution, reflecting the acknowledgement among most MENA states that their national domestic efforts are likely to be insufficient for a totally effective vaccination program. Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Oman, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia have all agreed down payments for the COVAX Facility, which would, in theory, guarantee vaccines at discounted prices for up 20% of their populations by the end of 2021. Algeria, Egypt, Mauritania, Morocco, Syria, Tunisia, the Palestinian Authority controlling the West Bank and Gaza, and Yemen all qualify to be in the World Bank's group of lower middle-income countries for Gavi-COVAX Advance Market Commitment, meaning that they would qualify for supplies of donor-funded vaccines for end-2021 - also for 20% of their populations.

The MENA region has manufacturing capacity for vaccine production, either of vaccines licensed from international pharmaceutical companies or of domestically developed vaccines, which will likely increase regional supply options later into 2021. For instance, Turkey's domestic pharmaceutical sector is working on the production of a domestically tested and produced vaccine, which will likely support stock procured internationally, also preparing Turkey to take advantage of future vaccine diplomacy outreach - most likely in sub-Saharan Africa. In December 2020, Iran began the human trial stage of a domestic vaccine, COVIran Barekat, produced by Setad Ejraiye Farmane Hazrate Emam (Setad; Headquarters for Executing the Order of the Imam), a parastatal under the direct control of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. In addition, the Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Institute is starting human trials of another vaccine, Razi COV-Pars. Meanwhile, Egypt has approved the regulatory framework for production of China's Sinovac vaccine, while Algeria, Israel, and Morocco all have extensive domestic pharmaceutical sectors.

Mass protests increasingly likely for MENA states with incomplete political transitions through 2021, reflecting frustrations with government and slow vaccine rollout discontent

Disruptive protests against failing or transitional political systems took place in Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Tunisia in 2020 and these are likely to continue and grow in frequency in 2021. Most of the civilian populations are likely to be extremely unwilling to comply with any further imposition of restrictions on movement or the economy. If these countries' governments attempt to impose such containment measures while not providing sufficient state financial support or wide-ranging vaccination programs over the first half or 2021, the likelihood of nation-wide protests will increase significantly. For MENA states where the informal economy accounts for a large proportion of the workforce, such as Egypt, Jordan, and Morocco, prolonged economic lockdown measures or curfews are likely to galvanize protesters, particularly as previous state support funds are likely to be depleted.

Likewise, there will be a high risk of social unrest for governments perceived to be mismanaging vaccine rollouts due to already diminished civic infrastructure and weakened state finances; for instance, potentially in Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Tunisia. Failures to ensure appropriate vaccine rollouts will become fodder for further political infighting, contributing to increasing unrest risks and, in some instances, increasing the likelihood of governments being removed or stepping down. Of these, Algeria, Lebanon, and Tunisia, with already existing protest movements, which saw setbacks in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, are likely to be the most vulnerable to a change of government.

MENA states weakened by ongoing civil violence will likely be limited in ability to secure adequate vaccine supply and delivery, driving regional viral spread and potentially mutations

COVID-19 data for conflict zones in the region - Iraq, Lebanon,

Libya, Syria, and Yemen - remain scarce, but years of political

instability, weak governance capacity, and especially economic

sanctions will restrict governments' ability to secure adequate

vaccines for their populations. Although Iraq, Lebanon and Libya

have all made commitments to the COVAX Facility, this would

guarantee coverage for 20% of their populations by end-2021. Syria

and Yemen additionally qualify for donor-funded doses of vaccine

through the Gavi-COVAX Advance Market Commitment, but deliveries of

these are likely to face delay because of vaccine production and

distribution limitations, as well as COVAX's difficulties in

reaching its USD6.8-billion fundraising target.

Even with some vaccine supply secured, administering vaccination

campaigns in conflict zones will face unique logistical challenges.

Without a declaration of widespread ceasefires or amnesties to halt

conflict temporarily and allow for wider vaccine distributions and

testing regimes to be put in place, it is almost certain that the

COVID-19 pandemic will persist. With highly porous borders

facilitating the movement of people, both militants and refugees, a

lack of effective pandemic management, especially as conflicts

likely intensify in spring and summer 2021 (such as in Yemen), will

open the door for any new virus mutations to spread beyond conflict

borders into the wider MENA region.

Non-state regional actors are likely to capitalize on gaps in vaccination campaigns, to escalate violence and consolidate territorial gains

In Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State and other jihadist groups will probably try to exploit the economic damage already caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and government failures intensified by the need to prioritize a mass-vaccination program. Continued government inability to secure vaccines, and the likely inadequacy of cooling and medical infrastructure in the hot summer months, will facilitate an increasing mortality rate and will probably serve to aid recruitment by militant groups. The Islamic State's activity is likely to increase in the lead up to Ramadan, running from 12 April to 12 May in 2021, and continue into summer. The Islamic State will also likely seek to disrupt Iraqi elections scheduled for October 2021.

Governments without full control of territory, such as in Syria and Yemen, are also likely to see non-state actor groups leverage access to populations in exchange for territorial recognition. Ansar Allah (the Houthi movement), for example, has almost full control of northern Yemen and is unlikely to accept any compromise agreement to allow vaccination access that does not include the recognition of its territorial gains. Instead, IHS Markit assesses that it is likely to push to expand further the territory under its control. The movement has exploited previous ceasefire agreements to regroup and is likely to consider the reduced US support for the Saudi-led coalition as a new opportunity to escalate fighting with Yemeni forces and intensify targeting of Saudi territory.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitical-implications-vaccine-rollout-mena.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitical-implications-vaccine-rollout-mena.html&text=The+geopolitical+implications+of+vaccine+rollout+programs+across+MENA+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitical-implications-vaccine-rollout-mena.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=The geopolitical implications of vaccine rollout programs across MENA | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitical-implications-vaccine-rollout-mena.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=The+geopolitical+implications+of+vaccine+rollout+programs+across+MENA+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitical-implications-vaccine-rollout-mena.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}