Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Mar 16, 2021

The G20’s Common Framework

The G20 launched the 'Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI' in November 2020, with Chad becoming the first country to join on 27 January 2021, followed by Zambia and Ethiopia. The Framework is intended to co-ordinate debt reprofiling and restructuring undertaken by official and private creditors, extending in scope beyond the modest debt deferral available under the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI). A key principle of the Framework is to incorporate non-Paris Club member lenders, such as mainland China, India, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Turkey, in addition to private creditors, to ensure "fair" burden sharing across all creditors.

Market access fears

The key concern for eligible countries is whether the Common Framework will restrict access to borrowing in commercial markets or raise debt servicing costs, given the risk of credit rating downgrades and/or deterioration in market reputation as a result of seeking to reschedule private-sector liabilities. The concerns have been exacerbated by a lack of co-ordination between the Paris Club, private creditors, and ratings agencies during the DSSI's launch, which contributed to a perception that agreement to the deferral of official bilateral credits necessarily implied the subsequent eventual deferral of private credits.

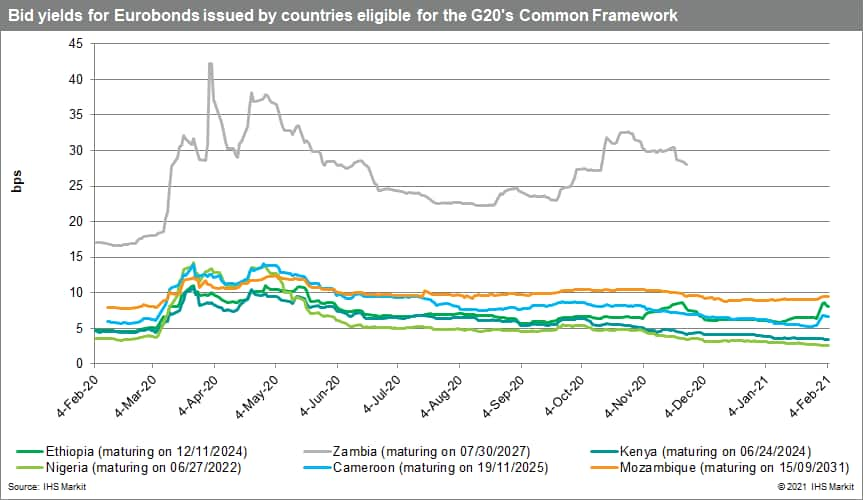

However, there has so far been little evidence of any adverse market reaction towards the wider asset class of Emerging Market borrowers: focus has been primarily limited to the applicant countries of Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia, suggesting that contagion to other borrowers would be limited. There are some isolated exceptions. Cameroon's increased yield is likely to stem from its membership of the Economic and Monetary Community in Central Africa, of which Chad is also a member. The smaller increase for Mozambique reflects the stalling of LNG project developments. In any case, yields across sub-Saharan African issuers had already returned to pre-COVID-19 levels by the end of 2020, with minor upward changes in yield only being recorded in Ethiopia, Cameroon, and Mozambique (increases of 2.04, 1.43, and 0.47 basis points, respectively, from 29 to 30 January) after Ethiopia's Finance Ministry announced its intention to participate in the Framework on 29 January 2021.

From debt restructuring to suspension

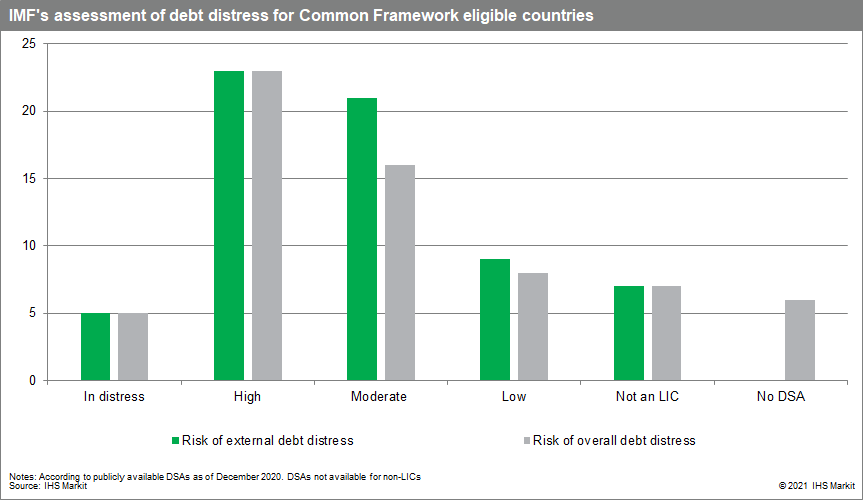

The Common Framework goes beyond the temporary relief provided by the DSSI to consider further debt treatment options that support long-term debt sustainability. At present, the G20 has provided very few details on how the Framework will be operationalized, aside from specifying the IMF's role in assessing debt sustainability and providing program support, with the Fund to retain its preferred creditor status. Participants are expected to undertake the IMF's Debt Sustainability Assessment (DSA) and an IMF program involving policy reforms and provision of additional IMF financing.

The IMF's Executive Board retains discretion over how to judge any breaches of debt distress thresholds and whether there are country-specific factors not covered by the DSA that contribute to such breaches. The resulting parameters of the DSA are then established under a legally non-binding Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), with creditors implementing the MoU through bilateral agreements with the debtor.

Private creditor participation: A major obstacle to debt relief

The DSSI has been unable to secure the participation of any private creditors. The International Institute of Finance - the body representing private creditors - established terms of reference for sovereign borrowers to engage with private creditors (including waivers to prevent the triggering of default and cross-default clauses), but so far this has not been used. One key reason on the creditors' side is that the DSSI implies irretrievable losses, contravening creditors' fiduciary responsibility to protect their clients' investments. The DSSI defers liabilities to spread debt service burdens but does not write them off, with the contractual rate of interest remaining in place for the amounts due once the five-year deferment period has ended.

To achieve wider creditor participation, the Framework would need to address four key shortcomings on the creditor and debtor sides.

- Enforcement: Private creditors' participation is voluntary: there exists no supranational legal mechanism to compel their involvement. Without enforcement, the Framework will suffer from "free rider" issues and disagreements over the seniority of payment obligations.

- Co-ordination: The Framework does not specify a mechanism to organise creditor committees spanning both private and official lenders. Historically the IMF has been reluctant to co-ordinate creditors. Even among private creditors, co-ordination is often difficult given the diverse range of claims against a sovereign via different types of debt instrument, especially the increased use of collateralised debt and contingent liabilities such as guarantees.

- Transparent debt reporting: The Framework would need to ensure that all bilateral creditors (including Chinese state-owned lenders) provide accurate and transparent accounts of their lending to eligible countries.

- Preventing litigation and holdout behaviour by bond holders: Sovereign debt has no automatic bankruptcy mechanism and there is no supranational framework for managing debt workout

This blog post was written with contributions from Anton Casteleijn, Senior Economist; Archbold Macheka, Economist; John Raines, Associate Director; Petya Barzilska, Senior Research Analyst; and Brian Lawson, Economic and Financial Consultant

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fg20s-common-framework.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fg20s-common-framework.html&text=The+G20%e2%80%99s+Common+Framework+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fg20s-common-framework.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=The G20’s Common Framework | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fg20s-common-framework.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=The+G20%e2%80%99s+Common+Framework+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fg20s-common-framework.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}