Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Mar 25, 2021

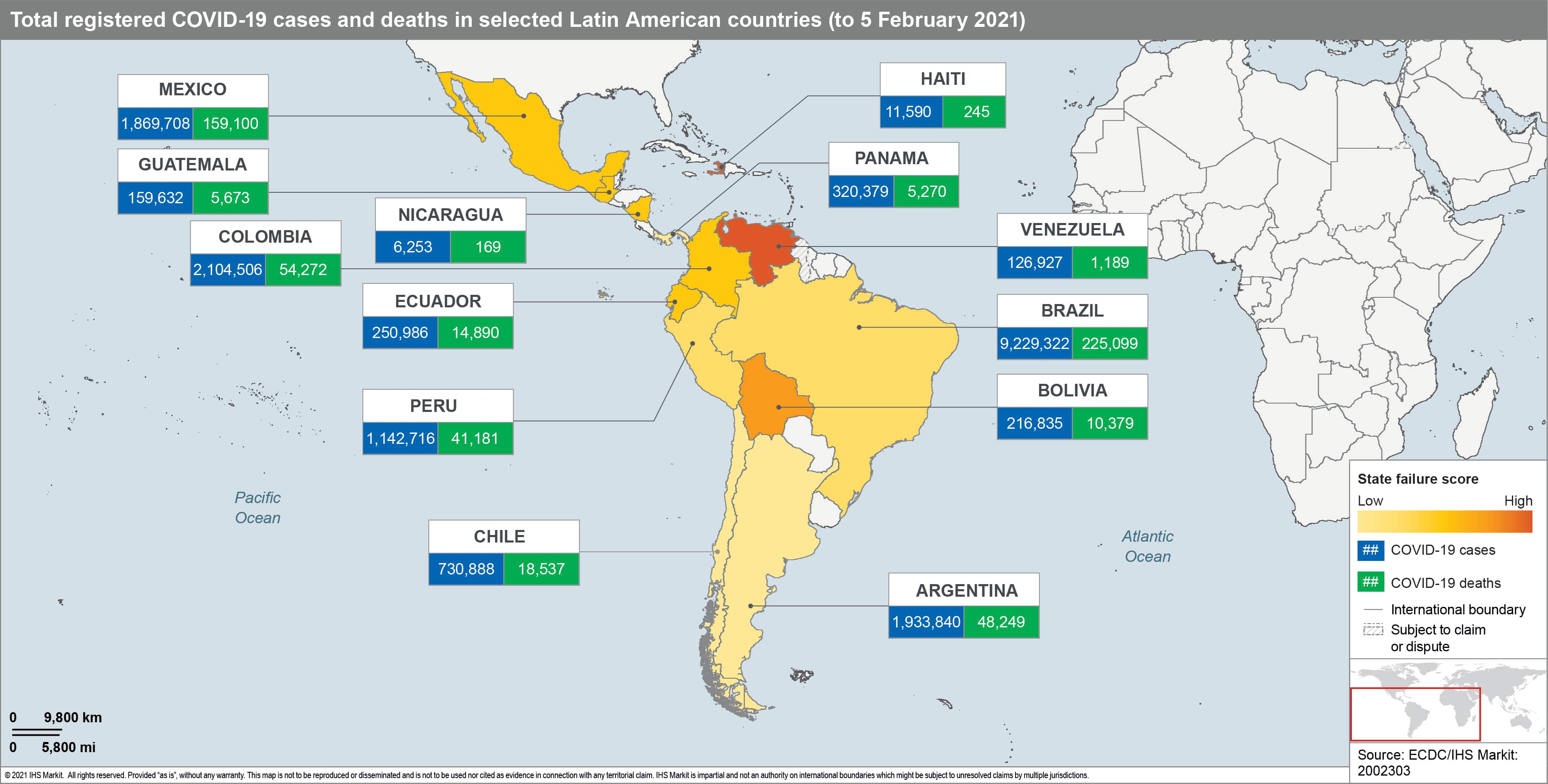

The geopolitical implications of vaccine rollout programs across Latin America

Vaccine access will be limited in the region by reliance on

external sources

Cuba is currently preparing to test the region's most advanced

locally developed vaccine, Soberana 2; however, this is likely to

take several more months to become available for use and even then

production capacity on the island is likely to be very limited.

Therefore, the rest of the region will remain dependent on

acquiring vaccines from external sources in 2021. Most Latin

American countries have become increasingly open to accessing

COVID-19 vaccines from diverse sources to balance the risk of

supply shortages and delays. Larger countries including Argentina,

Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay,

and Venezuela have vaccine acquisition purchase agreements (APAs)

in place and are also participating in the World Health

Organization's pooled procurement mechanism under the COVID-19

Vaccines Global Access Facility (COVAX) framework. Colombia has so

far signed the most APAs with companies (five), with Mexico, Peru,

and Chile also in stronger positions to cover larger proportions of

their populations with four, three, and two APAs signed,

respectively. Argentina is further behind in terms of number of

doses compared with population needs and will need to secure more

vaccine supply.

Smaller countries such as El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, and Nicaragua will be more heavily dependent on the COVAX facility; however, this mechanism only plans to provide vaccines for up to 20% of each participating country's population. Therefore, to vaccinate more than 20%, these countries will have to seek additional funds from alternative private or multilateral sources, such as the announced funding of USD1 billion from the Inter-American Development Bank in December 2020. Many countries with COVAX facility agreements also have yet to confirm a date for the arrival of the first vaccine doses. Vaccine quantities are highly likely to remain insufficient in poor and middle-income countries during 2021, with the Jamaican health ministry estimating in January that only 16% of its population will have been vaccinated by the end of the year.

Domestic distribution will be delayed by regulatory, logistical, and political constraints

It is already evident that securing vaccine supply agreements is not enough in itself to ensure a successful rollout. For example, Colombia has more APAs in place than other countries, but it has yet to start vaccinating its population, while Argentina has fewer APAs but was among the first in the region to begin vaccinations in December. Moreover, companies including US vaccine manufacturer Pfizer and the Russian developers of the Sputnik V vaccine have already announced expected supply disruptions that will affect Latin America.

Successful vaccine distribution will be likely to depend on additional factors, including individual countries' regulatory approval mechanisms, supply-chain logistics, levels of bureaucracy, and the availability of trained personnel, medical equipment, and cold refrigeration. For Latin America, one of the main logistical challenges associated with vaccinating the majority of individual countries' populations is reaching more rural and remote areas that, in many cases, have a poor existing transport and public health infrastructure.

There is a high risk of political disputes emerging between the central and regional/state governments over distribution plans as rollouts begin. This is highest in larger countries such as Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, where individual states or regions already have greater degrees of autonomy and population diversity. In Mexico, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador contradicted health ministry recommendations to grant state governments the ability to source vaccines independently; Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro publicly opposed São Paulo state government's production and use of the Chinese CoronaVac vaccine; and Colombia's central government halted Cali department's unilateral negotiations with a vaccine supplier in favour of retaining central management of the vaccination plan.

Vaccine security risks are highest in Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico

Criminal activity will also disrupt vaccine rollout through theft attempts of vaccines and associated equipment by highly organized criminal groups in countries such as Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico and from hospitals by corrupt officials or workers. This includes armed theft risks while in transit through areas where organized criminal groups are already active (for example on highways in Brazil's Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo states and Colombia's Caquetá, Putumayo, and Arauca departments), but also from hospitals and storage facilities. Online counterfeit vaccine sales are also highly likely to increase this year, exacerbated by delays and scarcity. Such sales have already been reported in Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Paraguay since December 2020 and could eventually affect vaccine uptake if they become widespread.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitical-implications-vaccine-rollout-LatAm.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitical-implications-vaccine-rollout-LatAm.html&text=The+geopolitical+implications+of+vaccine+rollout+programs+across+Latin+America+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitical-implications-vaccine-rollout-LatAm.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=The geopolitical implications of vaccine rollout programs across Latin America | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitical-implications-vaccine-rollout-LatAm.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=The+geopolitical+implications+of+vaccine+rollout+programs+across+Latin+America+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fgeopolitical-implications-vaccine-rollout-LatAm.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}