Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Mar 09, 2022

Financing sub-Saharan Africa’s energy transition

The African Group of Negotiators on Climate Change (AGN), the technical body of Africa's three-tier negotiating structure, is planning to meet from March 14-17 in Livingstone, Zambia to review the outcome of last year's United Nations Climate Change Conference of Parties (COP26). Discussions will focus on the outcomes of COP26 on sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), ahead of COP27 due to be held in Egypt in November 2022.

Key points

- SSA countries achieved substantial pledges of renewed financing at COP26, although these fall short of estimates of the total funding needed for loss and damage from, adaptation to, and mitigation of the effects of climate change.

- Regional development and multilateral financial institutions are stepping in to fill the financing gap, although it is still not enough; the cost of the climate change transition is estimated at USD1.7 trillion in SSA alone by 2030 (100% of SSA's GDP as of 2020).

- Further, lags in regulatory development and aligning of countries' climate change agendas with economic development plans are hurdles to accessing allotted funding.

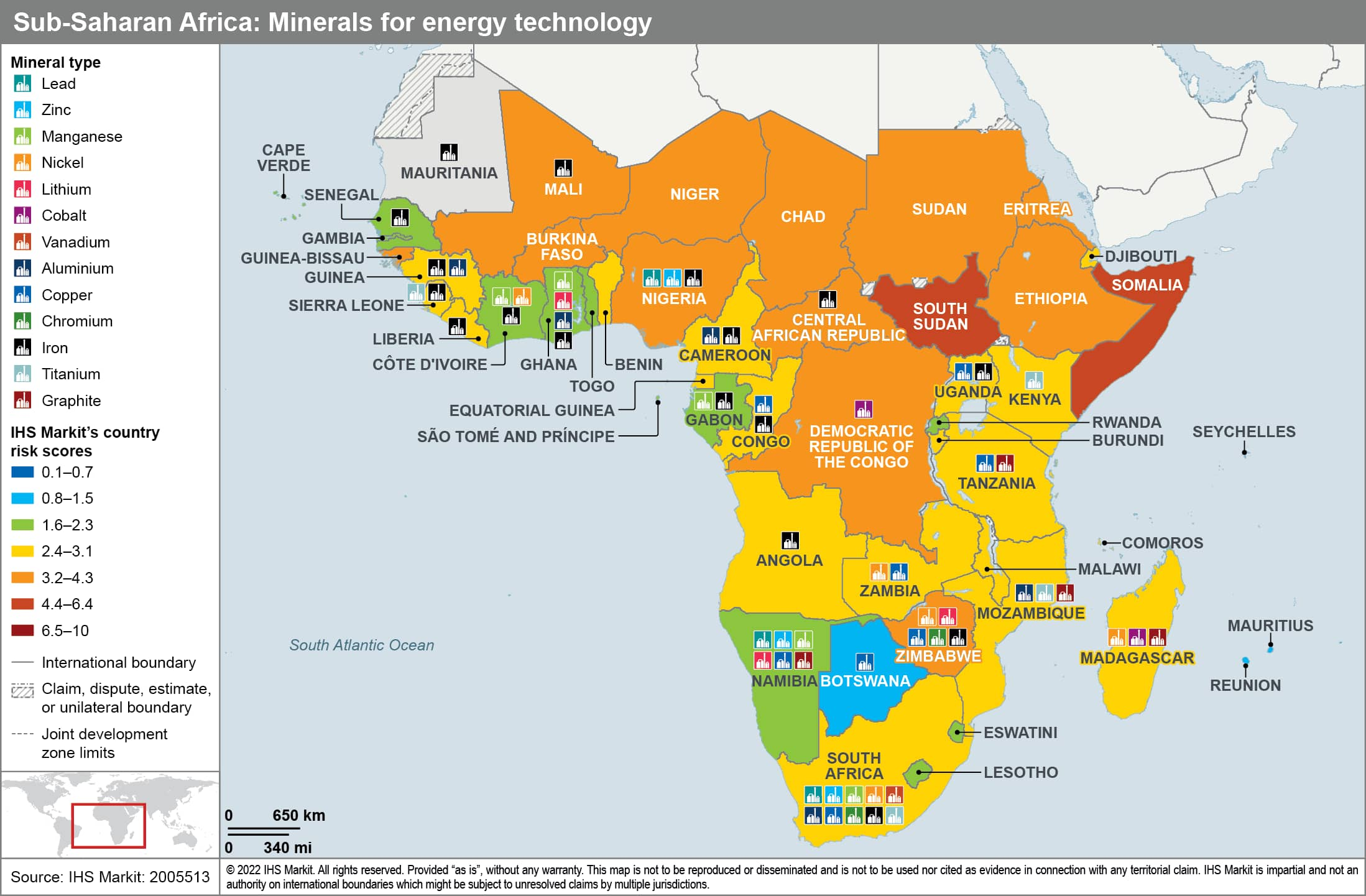

- Some SSA countries, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, South Africa, and Zambia, are likely to benefit from the opportunities derived from climate change mitigation and decarbonization in key sectors such as power, transport, agriculture, construction, mining, and natural gas.

SSA countries received insufficient financial pledges at COP26 to cover their full climate adaptation needs, but they did receive substantial commitments

UNFCCC estimates indicate that about USD125 trillion of direct capital investments are needed to transform the global economy and avoid the worst physical impacts of climate change by 2050. Of this, about USD32 trillion of investments is needed by 2030, out of which USD1.7 trillion (5.3%) of this amount is required in SSA - that is, USD170 billion per year. This equates to 100% of the region's GDP in 2020. Renewed pledges for adaptation made at COP26 equate to USD40 billion in funding by 2025, but this falls short of estimates by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) that annual adaptation costs for developing countries would total USD70 billion. Despite the huge financing challenges ahead, some SSA countries did manage to secure important financing deals at COP26 to support their individual energy transition plans. South Africa - the continent's most industrialized economy and largest carbon-dioxide (CO2) emitter - secured a USD8.5-billion deal under the Just Energy Transition Partnership with the United States, the European Union, and several individual European countries, a climate-finance swap to close several coal-fired power plants and launch renewable projects to replace them. However, to unlock this funding, the South African government is very likely to be required to build a viable pipeline of eligible projects.

SSA governments face growing difficulty in attracting funding for carbon-intensive projects since investors are focusing increasingly on environmental, social and governance (ESG) objectives.

There is a broad consensus among the world's leading donor countries to end international financing of projects producing carbon-intensive fossil-fuel energy sources, namely coal and upstream oil. The pursuit of ESG objectives has already resulted in the withdrawal of financing commitments to projects in the sub-Saharan Africa region. For example, in November 2021, China announced that it would no longer finance a 3-megawatt coal power plant in South Africa's Limpopo province. Narrow support for midstream and downstream natural gas projects remains, but upstream natural gas projects face even greater financing challenges. The European Commission published the Complementary Climate Delegated Act, which deems natural gas a 'transition' energy source, making the investment in natural gas projects compatible with the EU's 2050 net-zero goal. Similarly, the World Bank stated that it would, in "exceptional circumstances", support upstream natural gas projects. Nonetheless, financial disclosure requirements regarding carbon emissions, pressure from shareholders, and concerns of 'green-washing' among potential investors when raising capital appear increasingly likely to reduce the appetite of regional and domestic financial institutions, including sovereign wealth funds, to continue support to hydrocarbon projects. Consequently, fossil fuel projects are likely to face increasing difficulty in finding investment guarantees, political risk insurance, and performance bonds, typically sought to mitigate project risks, perceived to be high in SSA.

Regional multilateral development banks (MDBs) and private capital sources are unlikely to fill the gap left by traditional financing sources.

African governments are likely to turn to regional MDBs, domestic financial institutions such as sovereign wealth funds and pension funds, and aspirational regional middle-class private investors with investment capital to fund strategic fossil-fuel projects. For example, on 27 January 2022, African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank) announced USD5-billion funding for Nigeria's national oil company, Nigerian National Petroleum Company Ltd, under a resource-backed loan arrangement for greenfield and brownfield projects in the country's upstream sector. Private investment from domestic sources is also likely to increase in upstream fossil fuel projects. In Tanzania, local firm Mirambo Mining bought a controlling stake in Tancoal Energy, which, from its Ngaka coalfield, is reportedly East Africa's biggest supplier of the fuel.

SSA countries are likely to benefit from a range of new revenue sources relating to the energy transition

Agreement at COP26 on Article 6 rules under the Paris Agreement has opened up a potential new avenue for SSA countries to tap growing international demand for offset projects in voluntary carbon markets, which in 2021 achieved over USD1 billion a year in nominal trade. The International Emissions Trading Association estimates that Article 6 could lead to a reduction in the total cost of NDC implementation by about USD250 billion per year in 2030. Although Africa currently accounts for less than 3% of global carbon trading, Gabon announced plans to place up to USD5 billion of carbon credits on the market in 2022 after passing its climate law in September 2021. Gabon possesses 13% of the Congo Basin rainforest, absorbing 100 million tons of CO2 (net) per year. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has similar ambitions to secure funding for preservation efforts in its portion of the Congo Basin, signing a USD500-million investment deal with the UK at COP26.

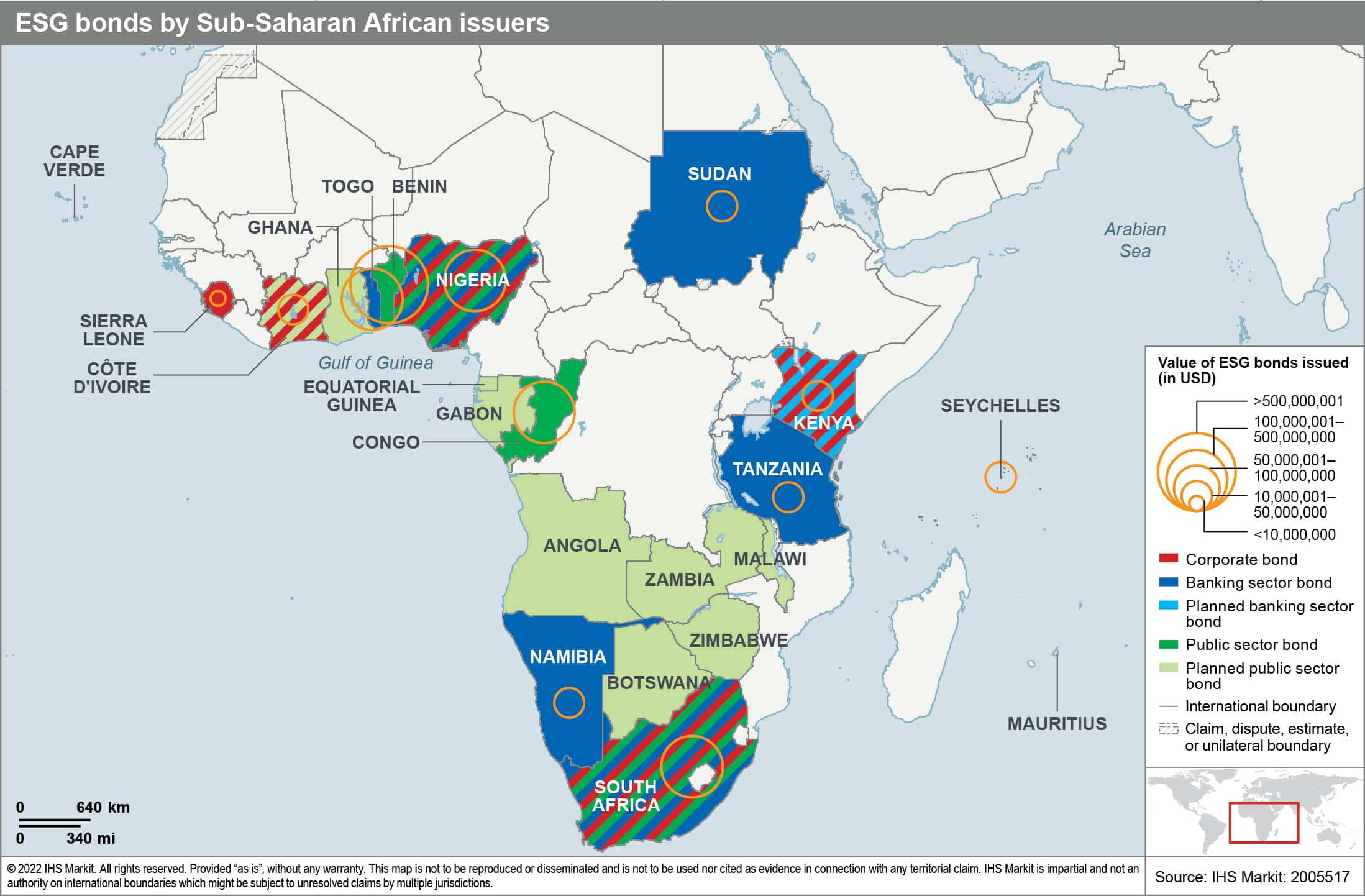

Finally, there has been some skepticism about the upside from Article 6 as it rules out double counting, creating a ceiling on carbon emissions for developing countries - particularly SSA with the lowest emissions globally (less than 4%). SSA countries that have issued green bonds (to support renewable energy projects, clean transportation, and climate adaptation projects) and blue bonds (to support sustainable marine and fisheries projects), at the sovereign and municipal levels, in recent times include South Africa (USD200 million in 2020).

Given that funding is increasingly likely to be prioritized and shifted towards clean energy, innovation, and energy efficiency, some SSA countries should benefit from the opportunities of mitigation and decarbonization in key sectors such as power, transport, agriculture, construction, mining, and natural gas

In this regard, countries such as Gabon, Ghana, and South Africa have commenced developing and implementing policies around a sustainable circular economy, particularly deepening renewable energy penetration in the total energy mix. Further, the EU Green New Deal's circular economy plan presents opportunities to localize parts of the value chain to African producers and strengthen value addition by promoting manufacturing - which will become even more critical as the EU's carbon border adjustment mechanism is introduced. Finally, African governments are seeking increased investments in new forms of resource-based industrialization using critical minerals such as copper and cobalt, which are vital for the energy transition and abundant on the continent.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2ffinancing-subsaharan-africas-energy-transition.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2ffinancing-subsaharan-africas-energy-transition.html&text=Financing+sub-Saharan+Africa%e2%80%99s+energy+transition+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2ffinancing-subsaharan-africas-energy-transition.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Financing sub-Saharan Africa’s energy transition | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2ffinancing-subsaharan-africas-energy-transition.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Financing+sub-Saharan+Africa%e2%80%99s+energy+transition+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2ffinancing-subsaharan-africas-energy-transition.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}