Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Mar 19, 2021

Is the eurozone at risk from another sovereign debt crisis?

- Positive changes since the Global Financial Crisis include fewer excesses and imbalances, the ECB's asset purchase programs, and the creation of the ESM and RRF.

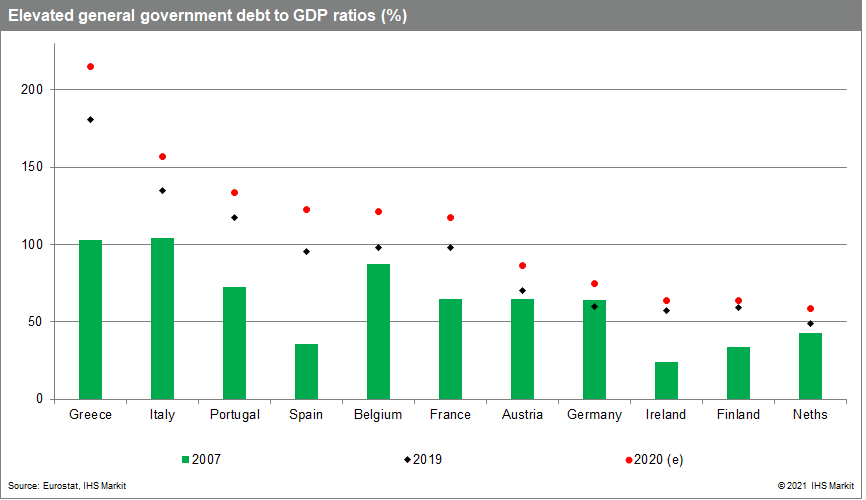

- However, following the COVID-19 shock, six eurozone member states will have public debt to GDP ratios well in excess of 100% and achieving sustained reductions will be difficult.

- Given low nominal GDP growth rates, lasting improvements in primary budget balances will be required even if interest rates remain relatively low.

- This will not be easy, given political constraints. Persistent, elevated debt ratios imply a high risk of more turbulent market conditions once the ECB starts to lessen its support.

Shaky foundations have been reinforced…

Long-standing concerns about the stability of the eurozone and its member states' public finances stem from a combination of structural challenges at national level and an inadequate infrastructure for the currency union. While the former remains a concern (discussed below), some welcome progress has been made on the latter.

Various institutional improvements and support mechanisms have been introduced since the Global Financial Crisis. These include 2012's creation of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), with a total lending capacity of EUR 500bn, plus 2020's agreement on the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), providing financial support to vulnerable member states, including via grants.

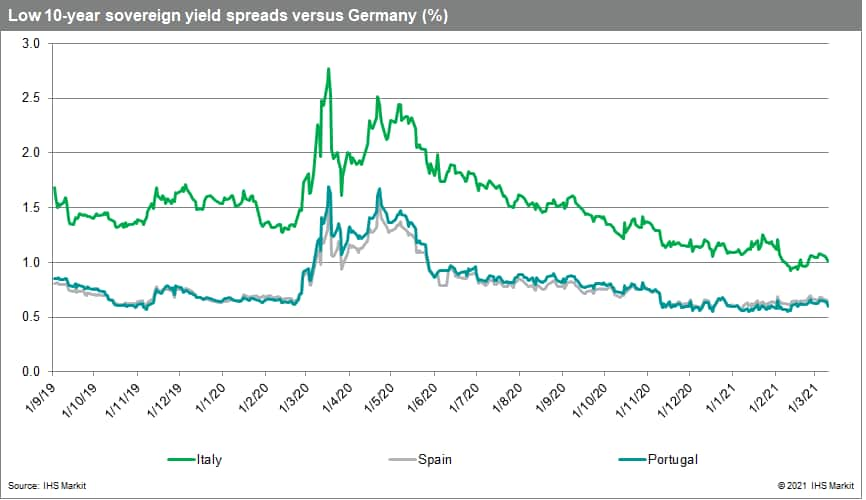

The ECB has also demonstrated its willingness to do whatever it takes to preserve eurozone financial stability via the creation of the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) framework in 2012 and its subsequent large-scale asset purchases under various programs, including the current Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program (PEPP). After a surge in the initial wave of COVID-19 in spring 2020, intra-eurozone yield spreads have remained relatively low and stable since.

…but high debt ratios will remain a source of vulnerability

While the chances of another full-blown crisis engulfing the eurozone have reduced given the changes above, there is still cause for concern. In particular, the vulnerabilities associated with persistently high public debt to GDP ratios in the aftermath of the COVID-19 shock. Six eurozone member states have ratios well in excess of 100%.

The debt to GDP ratio is not the sole metric determining sustainability. As long as interest expenditure remains low, elevated debt to GDP ratios can be sustained for some time. However, a sudden loss of investor confidence and a jump in financing costs can quickly destabilize the situation, with far-reaching consequences for economic and financial stability.

While the eurozone now has various support mechanisms in place to try to contain these effects, both the ECB's OMT and assistance from the ESM would require acceptance of formal macroeconomic adjustment programs. Governments will be extremely reluctant to sign up for such programs, absent sustained market pressure.

Uncomfortable fiscal arithmetic…

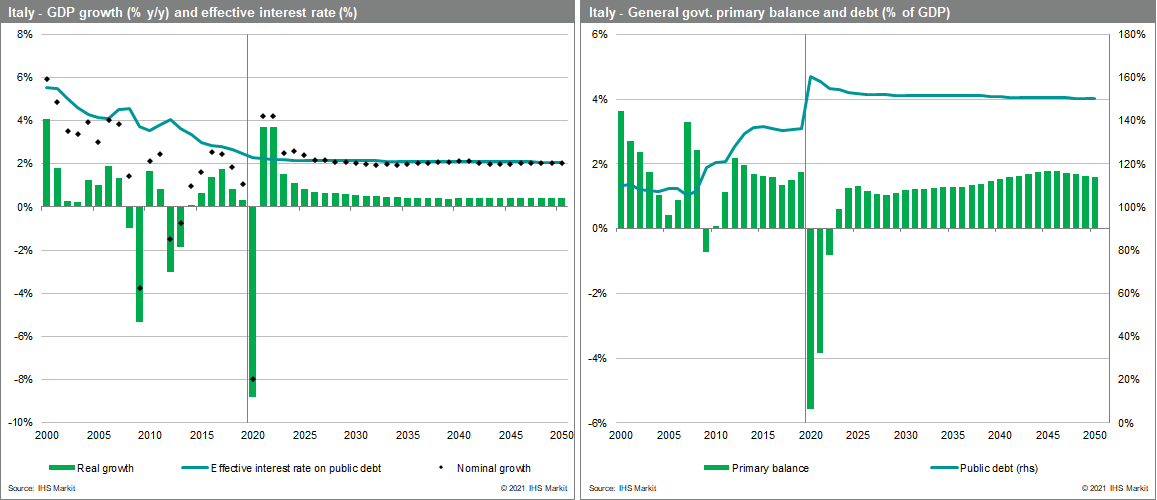

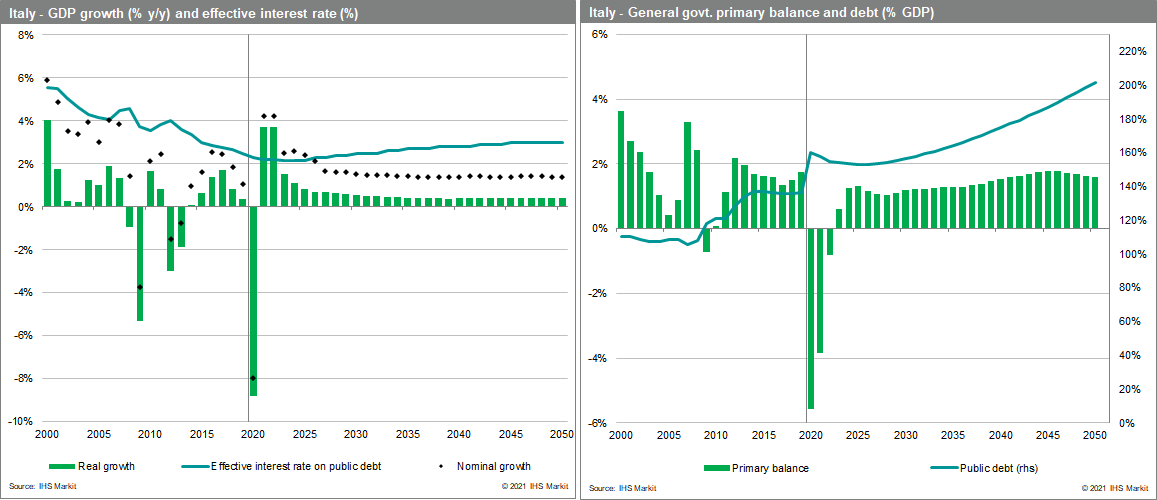

The evolution of public debt to GDP ratios typically depends on the interaction of three key factors: the nominal interest rate paid on the debt, nominal GDP growth and the primary budget balance (excluding debt interest). While debt service costs are exceptionally low at present, the longer-term prospects for nominal growth and primary budget balances in many of the most highly indebted eurozone member states are not favorable.

Debt ratios are unlikely to fall substantially, therefore, in the absence of prolonged fiscal adjustments. But such adjustments will be difficult to achieve and sustain. Forming a stable government is difficult in many member states and austerity is unpopular. Government revenues already account for very high shares of GDP in many member states, while sustained reductions in expenditure will run into strong opposition.

…including in Italy

Italy's situation illustrates the precarious nature of the fiscal metrics in highly indebted, low growth economies. Italy's public debt to GDP ratio is forecast to have peaked at just under 160% in 2020, up from 105% back in 2007. The long-standing upward trend in the debt ratio occurred despite Italy achieving sustained primary budget surpluses from 2008 to 2019 (with the exception of 2009). Having plunged into deficit in 2020, we forecast that the primary balance will return to return to surplus from 2023 onwards, remaining between 1-2% of GDP.

As GDP growth picks up in the immediate aftermath of COVID-19 but the ECB's asset purchases lean down on yields, the "snowball effect" on Italian public debt is favorable initially. But it soon fades, as real GDP growth returns to its meagre potential rate and inflation remains subdued. Italy's public debt to GDP ratio barely declines over the forecast horizon as a consequence, ending up at around 150% by 2050.

This is despite persistent positive real GDP growth rates, sustained primary budget surpluses and a very limited increase in interest rates throughout the forecast - highlighting Italy's vulnerability to adverse shocks. Alternatively, if we assume somewhat lower nominal GDP growth rates through the forecast period, along with a gradual upward trajectory for interest rates, the path for the debt to GDP ratio in Italy looks very disturbing, exceeding 200% by 2050.

ECB's support critical, but what if it steps back?

The good news is that the ECB is committed to providing extensive policy support for some time to come, prolonging the favorable combination of low interest rates and rebounding growth. Its asset purchases under the PEPP are being stepped up near-term and will continue until at least the end of March 2022 according to ECB forward guidance. Reinvestment of principal payments from maturing assets under the PEPP will continue until at least the end of 2023.

But thereafter, assuming the ECB wants to start scaling back its huge balance sheet, the situation will become much more unstable, necessitating credible fiscal consolidation strategies across the most highly indebted member states. If governments do not seem able or willing to deliver those adjustments, and the ECB will not step back in (absent agreements in favor of formal macroeconomic reform programs), the resulting stand-off would risk another eurozone crisis.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-risk-another-sovereign-debt-crisis.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-risk-another-sovereign-debt-crisis.html&text=Is+the+eurozone+at+risk+from+another+sovereign+debt+crisis%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-risk-another-sovereign-debt-crisis.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Is the eurozone at risk from another sovereign debt crisis? | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-risk-another-sovereign-debt-crisis.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Is+the+eurozone+at+risk+from+another+sovereign+debt+crisis%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-risk-another-sovereign-debt-crisis.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}