Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Jan 27, 2021

Eurozone—From deflation to reflation risk?

- Rising shipping costs and lengthening delivery times have reignited the discussion about a return of reflationary forces.

- Business surveys in the eurozone industrial sector have started to point to some upward pressure on factory gate prices and potentially core goods prices.

- However, it is way too soon to shift the focus from deflation to reflation risk in the eurozone, not least with a double-dip recession in train.

- Disinflationary trends have been entrenched for a decade and, looking beyond some near-term transitory upward pressures on inflation, are likely to persist.

Recent reports of substantial increases in container shipping costs and some supply chain issues, reflected in lengthening delivery times in IHS Markit's PMI data, have reignited the reflation versus deflation debate within the economics community.

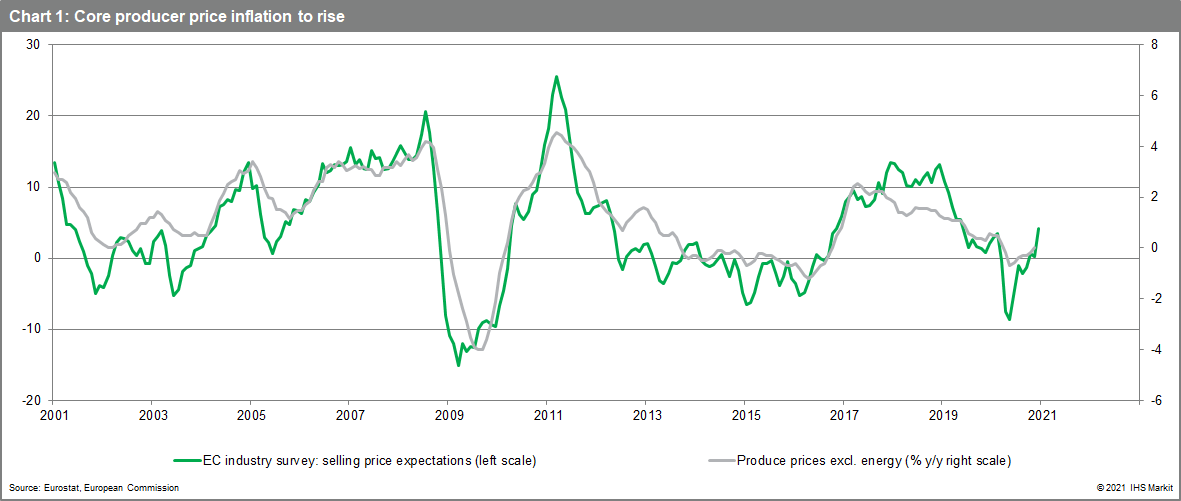

Even in the eurozone, there are signs here and there that pipeline price pressures are picking up. Surveys of selling price expectations among industrial firms started to rise in autumn 2020, in line with the strong rebound in manufacturing activity. The latest European Commission survey for December 2020 showed a marked pick-up, indicative of some upward momentum in core producer price inflation.

Perspective is required, however. The pick-up in PPI inflation is coming from very weak levels. The headline y/y rate of change has been negative since mid-2019, well before the pandemic, while the y/y rate of change excluding energy was zero as of November 2020. Moreover, while both rates will rise, whether higher factory gate inflation will pass through significantly into consumer prices is debatable given the difficult demand backdrop.

As yet, there is little sign of this happening. In fact, eurozone HICP inflation for non-energy industrial goods slipped further into negative territory in December 2020 (to -0.5%). Profit margins may take the strain given the tough economic climate.

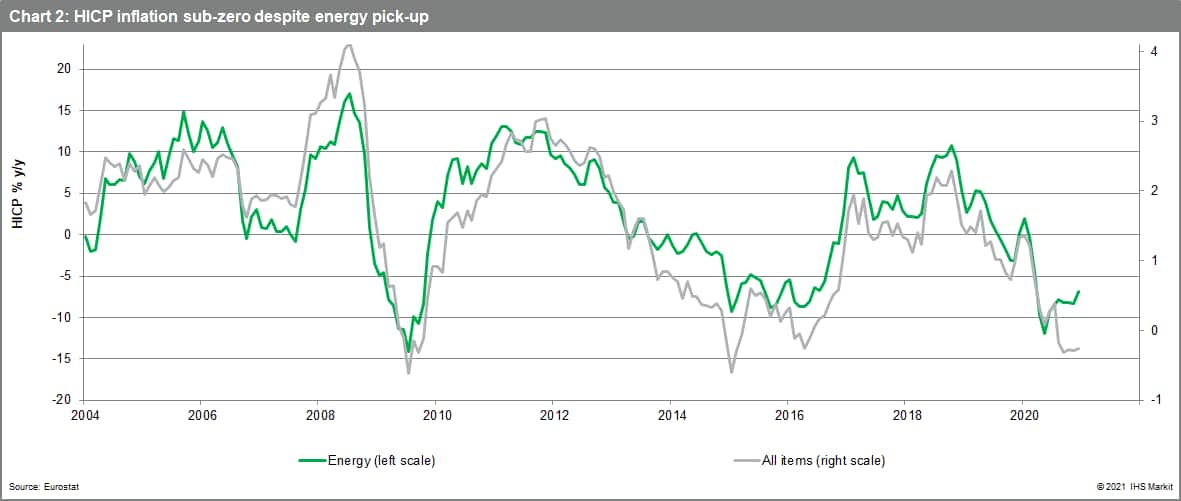

December's HICP data delivered a surprise in a negative direction in fact, with the headline inflation rate unchanged at -0.3% for the fourth month in a row despite upward pressure from energy, as prior oil price gains feed through.

Eurozone HICP inflation is set to rise in early 2021. In January, we expect the end of reduced VAT rates in Germany to push headline inflation up by around a quarter of a percentage point.

From February to May, upward base effects from energy prices are also likely to lean up on the headline inflation rate (subject to crude oil price dynamics in the coming months), given pronounced COVID-19-driven declines in oil prices in the equivalent period of 2020.

Also, some of the HICP items which have been most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic might also rebound as economic conditions improve later in 2021 once the restrictions ease. These include prices of clothing and footwear, package holidays, accommodation services and passenger transport.

However, we need to look beyond short-term transitory influences, to focus on the drivers of underlying inflationary pressures. These include wages and unit labour costs which, in turn, drive services inflation which is the predominant influence on overall HICP inflation.

Combine the eurozone's exceptionally large output gap (which is about to rise substantially further given the recession we forecast in Q4 2020 and Q1 2021), the likelihood of further rises in the unemployment rate and persistent low inflation expectations and the prospect of a sustained, wage-driven pick-up in inflation looks remote.

Add in the lagged effects of exchange rate appreciation, with the euro having risen to a record high in trade-weighted terms late last year, and we doubt that the reflationary arguments will endure for long beyond the expected pick-up in the months ahead.

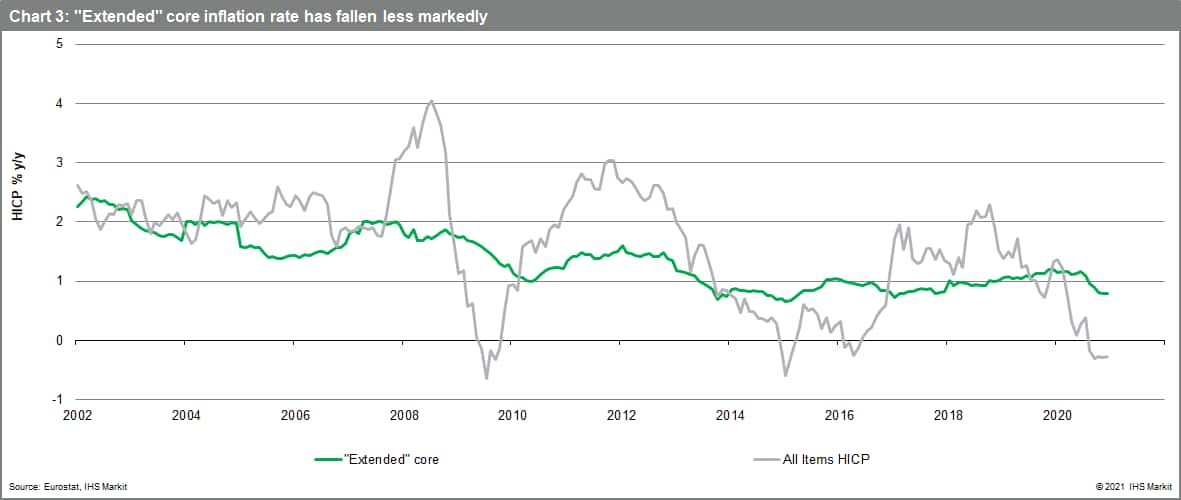

Consider the starting point for HICP inflation rates too. December 2020's final HICP figures confirmed the headline inflation rate below zero for the fifth straight month (-0.3%) and the traditional core rate at record lows, only marginally above zero (0.2%). IHS Markit's "super core" measure of inflation dropped back to its record low also (0.9%). It includes only the HICP items sensitive to the eurozone output gap, so ought to be more reflective of domestic economic trends than global influences.

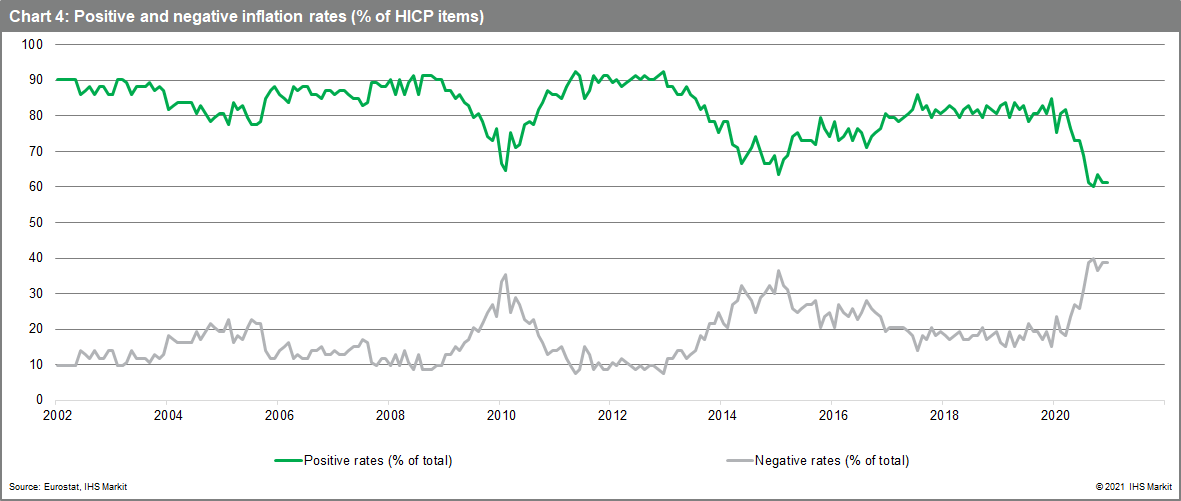

Moreover, in December 2020, the share of eurozone HICP items exhibiting negative y/y rates of change was close to its record high, at just under 40%.

With the exception of a short-lived, energy-propelled spurt in 2018, inflation in the eurozone has been well below 2% for nigh on a decade. Disinflationary forces look well entrenched and forecasters should be wary of getting ahead of themselves. The pick-up in eurozone growth from 2014/15 onwards was widely expected to yield higher inflation and higher ECB policy rates. Neither materialised.

We expect deflationary concerns in the eurozone to persist and we will continue to assess these risks via the broad range of inflation metrics we monitor in our Deflation Risk Dashboard.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-deflation-to-reflation-risk.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-deflation-to-reflation-risk.html&text=Eurozone%e2%80%94From+deflation+to+reflation+risk%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-deflation-to-reflation-risk.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Eurozone—From deflation to reflation risk? | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-deflation-to-reflation-risk.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Eurozone%e2%80%94From+deflation+to+reflation+risk%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-deflation-to-reflation-risk.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}