Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Feb 09, 2021

COVID-19’s legacy of high public debt in Europe: Prospects and problems

- High public debts in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic will present a vulnerability for European governments with strong incentives to stabilize and lower their debt-to-GDP ratios.

- Changes in public debt as a share of GDP are determined by the primary balance (balance without interest payments), the difference between nominal growth and interest payments (snowball effect), and deficit-debt-adjustment (also called stock-flow adjustment), which consists of financial transactions not included in the general fiscal balance.

- Since the 1990s, European governments have sought to lower debt-to-GDP ratios primarily through improvements in the primary balance (austerity), although this weighs down on growth and has had mixed results across economies over the last decade.

- Given weak potential growth rates across much of Europe, due to adverse demographics and other structural impediments, and the potential political fall-out from renewed austerity, more unconventional measures may be explored to help with the high public debt.

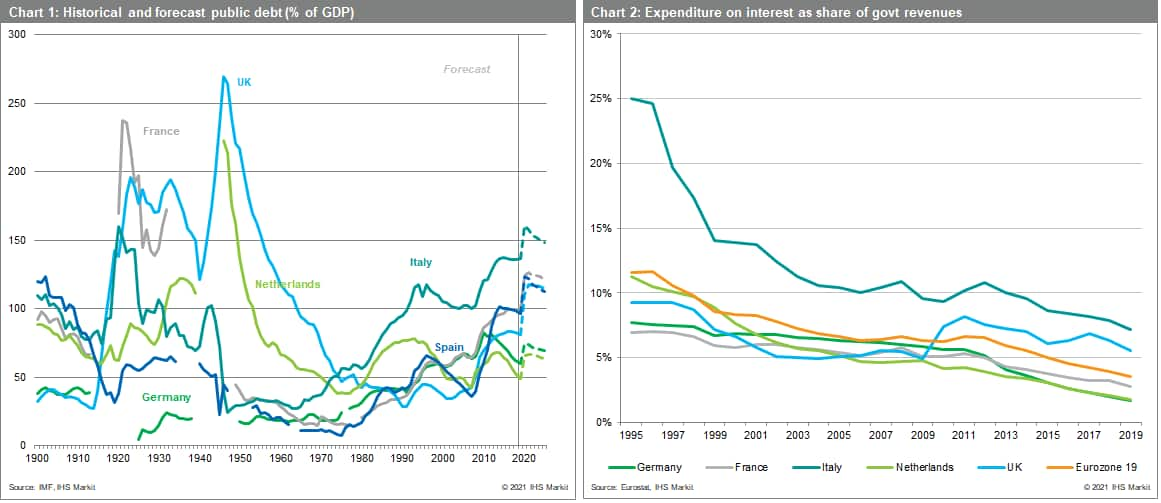

As a result of the fallout from COVID-19 and the extensive fiscal support measures, public debt to GDP in several European countries is set to match or surpass historical highs.

As long as interest expenditure remains sufficiently low, in line with the global trend over the last few decades, governments can live with debt stocks that are elevated by historical standards. However, elevated public debt does present some key risks, including:

- Vulnerability to a sudden tightening of financial conditions and unexpected shocks, which can disrupt market access or exacerbate rollover risks.

- High deficits and debt levels limit a government's ability to pursue counter-cyclical fiscal policy stimulus during economic downturns.

- Private sector under-investment due to uncertainty about future taxes.

Changes in public debt: a framework

Even in a low-interest-rate environment, governments will have incentives to lower their public debt in relation to GDP. The evolution of public debt-to-GDP ratios depends on these underlying drivers:

- Nominal interest rate paid on the existing debt.

- Nominal GDP growth.

- Primary budget balance.

- Deficit-debt-adjustment, which includes financial transactions not captured in the overall budget balance.

This can be expressed using a simple equation:

dt - dt-1 = dt-1((rt - gt)/(1+gt)) - pt + ddat

The key terms in the equation are defined as follows:

- dt is the debt-to-GDP ratio at t

- r is the nominal interest rate on the debt (the average rate of interest on debt outstanding, weighted by maturity)

- g is the growth rate in nominal GDP

- p is the primary budget balance

- dda is the debt-deficit adjustment

Put simply, nominal GDP growth running below the nominal interest rate on the outstanding debt would imply, other things being equal, a "snowball effect", whereby nominal debt increases more quickly than the size of the economy, and vice versa.

Lowering public debt to GDP ratios

The basic formula to lower public debt to GDP ratios is for real growth and inflation to be higher than the combined primary budget balance, interest expenditure, and the deficit-debt adjustment. There are several ways to achieve this, including:

- Grow out of debt with real growth outpacing real interest payments.

- Inflate debt away, historically often accompanied by financial repression.

- Fiscal policy adjustment to significantly improve the primary budget balance (austerity).

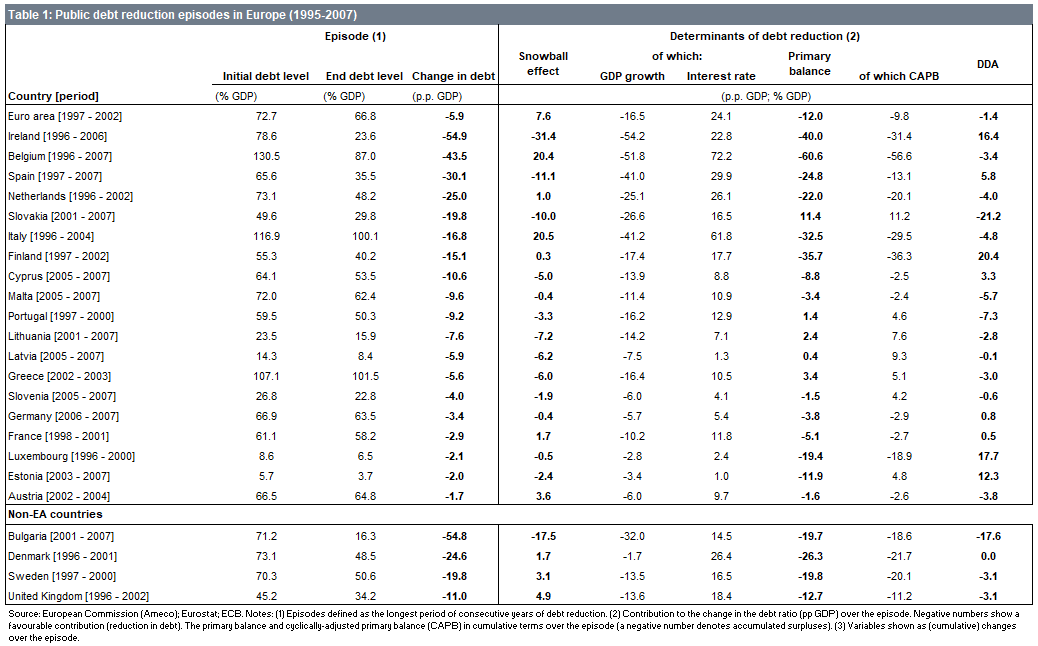

Table 1 shows recent episodes of public debt deleveraging across European economies. These include 10 instances between 1995 and 2007 in which the public debt-to-GDP ratio declined by more than 10 percentage points (pp.) in Western Europe.

On average, across the 10 Western European economies, public debt-to-GDP ratio declined by 25 pp., with the full adjustment coming via the primary balance component. Both the snowball effect (that is, the difference between nominal interest payments and nominal growth) and DDA added to the public debt-to-GDP ratio.

Of the 10 economies, only in Ireland, Spain, and Cyprus the snowball effect contributed to a reduction in their public debt-to-GDP ratios. However, in all three, the pre-global financial crisis period of high growth was accompanied by the build-up of significant macroeconomic imbalances, later resulting in a need for external financial assistance and painful macroeconomic adjustment programmes.

Two lessons can be drawn based on the experience of the public debt reductions in Western Europe in the decade or so prior to the global financial crisis:

- Changes in the primary balance (austerity) proved the only viable way to lower public debt-to-GDP ratios. Despite the secular decline in interest rates, nominal growth was not sufficiently strong to contribute towards debt reduction, without a build-up of significant macroeconomic imbalances in the process.

- The positive impact of substantial, effective austerity programmes can outweigh the adverse effects on debt ratios from the other components.

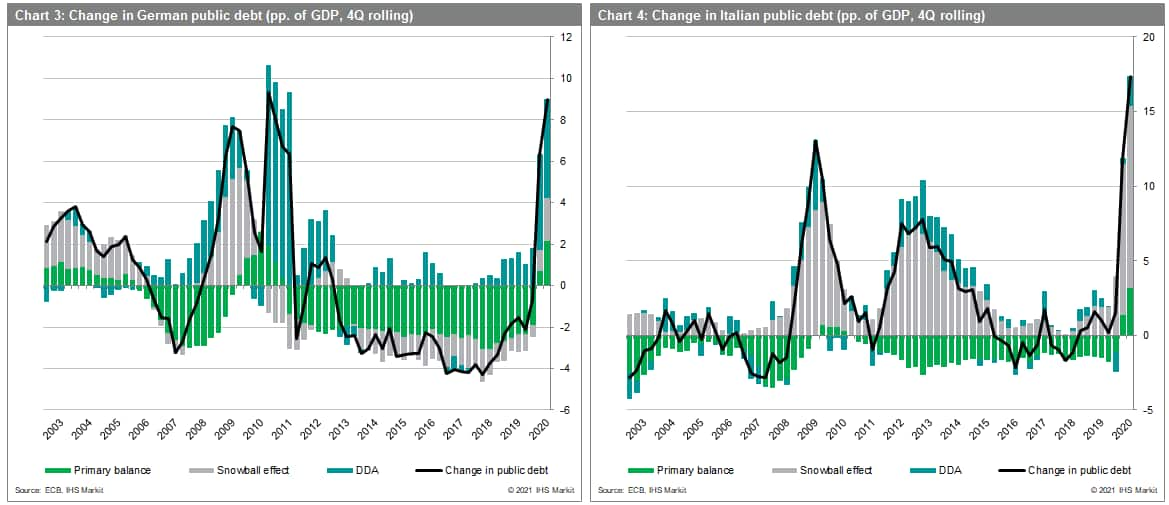

Italy and Germany after 2010

Perhaps driven by this experience, the response to the eurozone's escalating public debt vulnerabilities after the onset of the global financial crisis was centred on fiscal austerity. However, the outcomes were very different across economies.

From 2010 to 2019, both Germany and Italy ran significant primary budget surpluses, but Germany's public-sector debt-to-GDP ratio declined by almost 23pp. (from 82.3% to 59.6%), while Italy's ratio increased by more than 15pp. (from 119.3% to 134.7%).

Whereas in Germany, nominal growth outpaced interest payments over the period in question, with the snowball effect subtracting 8.1pp. from the public debt-to-GDP ratio, in Italy it added 23.2pp., far outweighing the contribution of the primary budget component, which lowered debt by 14.5pp. After 2010, the adverse snowball effect dominated as Italy's economy never recovered its pre-financial-crisis peak with real growth and inflation remaining anaemic.

Outlook

Given the unprecedented adverse shock from the COVID-19 virus pandemic, governments across Europe have rightly responded with large-scale fiscal support to try to mitigate the short- and longer-term negative effects on their economies. Although necessary, ballooning fiscal deficits have led to substantial increases in public-sector debt-to-GDP ratios, in many cases from already high levels.

As long as interest costs remain low, aided by central bank asset purchases, high debt-to-GDP ratios can be sustained for some time. However, they do entail various risks and once the post-COVID-19 recovery is well established, high debt burdens will need to be tackled.

Structural impediments to future economic growth across many European countries will make this very challenging, while prolonged fiscal consolidation risks suffocating growth still further and escalating social tensions. Therefore, alternative solutions including mutualisation and extensive ECB involvement are also likely to come under consideration further down the line, although both will face significant political hurdles.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcovid19-legacy-high-public-debt-europe.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcovid19-legacy-high-public-debt-europe.html&text=COVID-19%e2%80%99s+legacy+of+high+public+debt+in+Europe%3a+Prospects+and+problems+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcovid19-legacy-high-public-debt-europe.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=COVID-19’s legacy of high public debt in Europe: Prospects and problems | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcovid19-legacy-high-public-debt-europe.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=COVID-19%e2%80%99s+legacy+of+high+public+debt+in+Europe%3a+Prospects+and+problems+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcovid19-legacy-high-public-debt-europe.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}