Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Mar 24, 2021

Central Europe's consumer recovery from COVID-19 pandemic

- As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) virus restrictions are phased out, pent-up demand and a surge in household savings will support the post-pandemic consumer revival.

- The sectors with the biggest scope for a rebound after the pandemic are not necessarily those with the steepest declines in 2020. Some of the lost consumption will not be regained, especially as a share of consumers lose their jobs and businesses face bankruptcy.

- IHS Markit research indicates that the pandemic triggered a marked increase in inequality, with implications for consumption at both ends of the income spectrum.

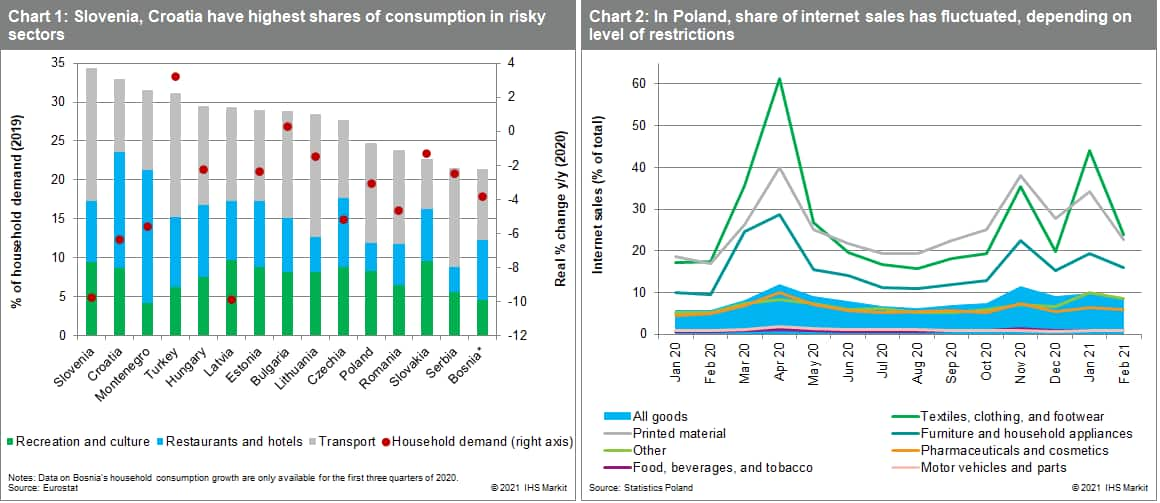

Although many CEE consumers have struggled amid COVID-19, 2020 demand growth varied dramatically by country and sector. Consumption of food, housing and utilities, and healthcare generally increased, while purchases of many other product categories declined, particularly those that were hit hardest by social distancing measures, such as tourism, entertainment, and transport. Across countries, the differences in household demand growth were influenced by the structure of consumption (reliance on sectors affected by COVID-19 restrictions), change in unemployment rates, and wage growth. Household credit growth was also important, playing an especially significant role in driving consumption in Turkey. Throughout the region, the rising importance of e-commerce helped prevent a steeper drop in household demand, although data from Poland indicate that consumers are returning to shops whenever restrictions ease, with positive implications for traditional retail.

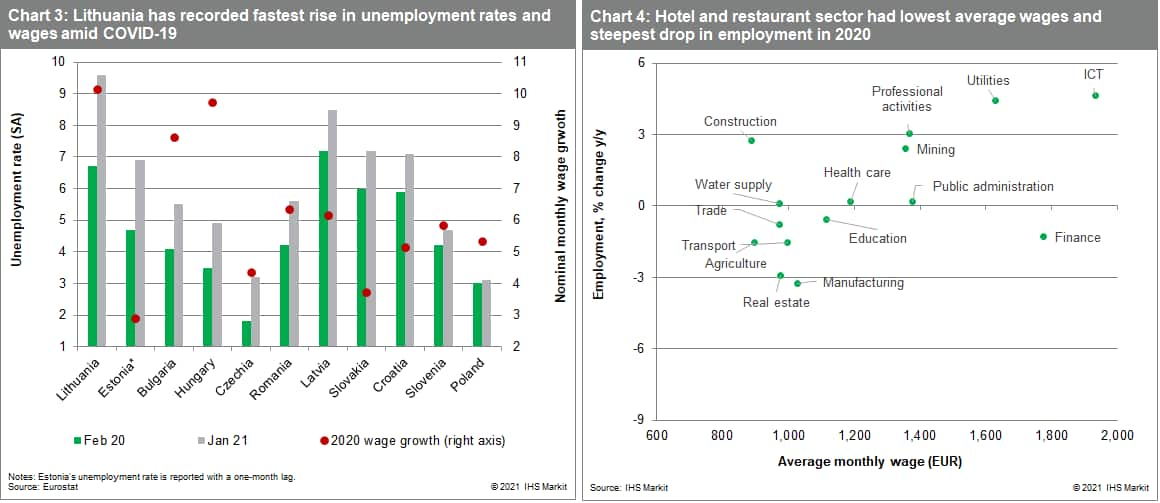

On the labor front, unemployment rates rose far less rapidly than expected last year, thanks to fiscal measures aimed at supporting employment. Lithuania and Estonia have recorded the biggest upswing in unemployment rates since February 2020, while Poland's jobless rate increased only slightly. Despite some volatility, average monthly wages rose across the region in 2020, with especially rapid growth in Lithuania, Hungary, and Bulgaria.

Data by sector across eight CEE countries indicate that healthcare and ICT recorded the fastest wage growth, which is unsurprising given the increased demand for ICT services and bonuses for medical workers. In contrast, hotel and restaurant wages recorded the steepest drop overall. On average, ICT and finance wages are the highest in the CEE region, while hotel and restaurant wages are the lowest. Employment data signal that the number of jobs in the hotel and restaurant sector fell in all eight countries, but other sectors showed divergent patterns.

Which countries and sectors will experience the fastest post-COVID-19 recovery?

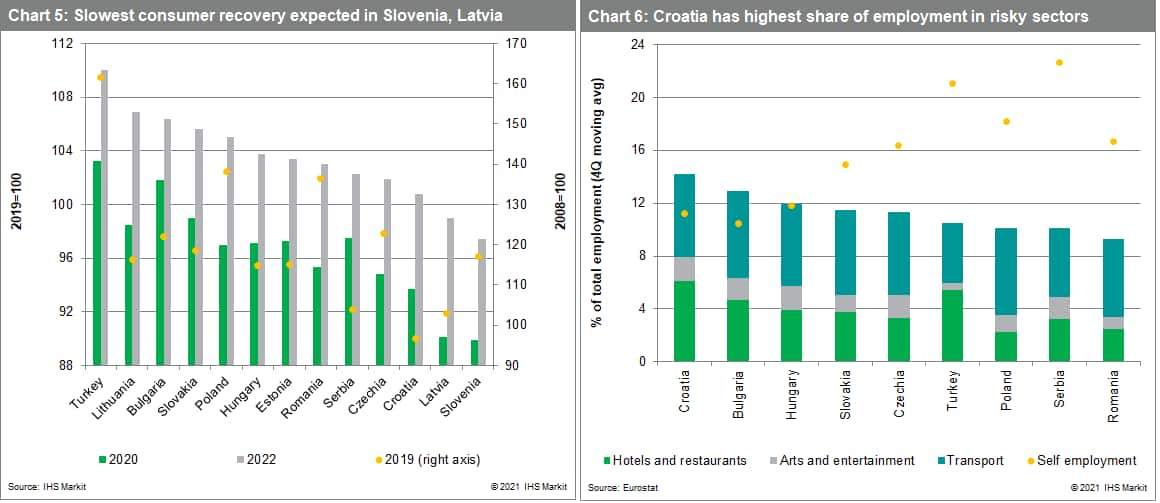

In its March forecast, IHS Markit is projecting that private consumption in most CEE countries will surpass 2019 levels by 2022. As a share of 2019 consumption, Turkey, Bulgaria, and Lithuania are expected to have the highest 2022 levels, partly thanks to a comparatively strong 2020 performance. In contrast, the revival of private consumption will be delayed in Slovenia and Latvia, partly due to the two countries' steep declines during 2020. Latvia (along with Croatia and Serbia) also experienced one of the region's slowest revivals from the 2008-09 global financial crisis (GFC).

As employment support measures are phased out, jobless rates are projected to increase in 2021, with negative implications for household demand. This is particularly true in countries that have experienced a protracted period of restrictions on economic activity owing to continued challenges related to COVID-19. Small businesses and the self-employed could face particularly high risks. Among CEE countries, Croatia has an especially high share of employment in vulnerable sectors, while Serbia and Turkey have large shares of self-employed. Even where jobless rates remain low in 2021, wage growth is likely to decelerate.

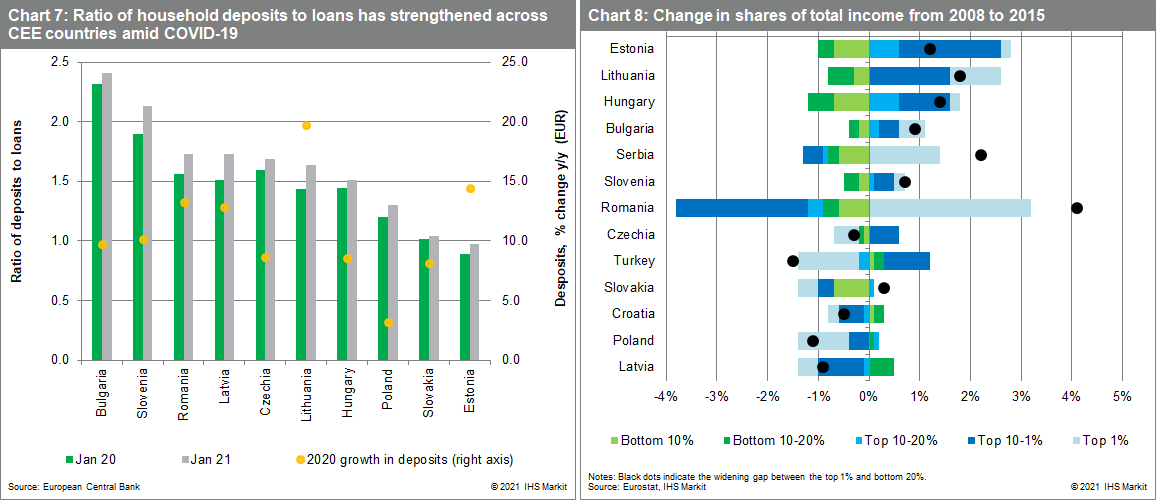

Savings to help fuel consumption during recovery period, but inequality is rising

While labor market pressures present downside risks, comparatively low household debt ratios and increased savings will support the region's consumer recovery in 2021. Social distancing restrictions and feelings of insecurity among the population contributed to a rise in household bank deposits during the course of 2020, further boosted by higher average wages. In most countries, household deposits significantly exceed the level of loans. Last year's rise in household savings is especially important when considering the outlook for investments in housing and renovations, as well as big-ticket consumer purchases such as automobiles, furniture, and household electronics and equipment. Higher bank balances could also help finance more extravagant vacations once COVID-19 restrictions are phased out.

Although savings data indicate considerable room for a rebound in spending as consumers release pent-up demand, there is likely a significant imbalance in deposits according to household income categories. Indeed, the population with lower incomes and education levels appears to have been hit harder by wage reductions and job losses, indicating that their savings were limited last year, a trend that will continue, or even heighten into 2021. Even as the economy reopens, lower income households are likely to save more as a precaution against the risk of additional shutdowns and possible unemployment.

While it is too early to tell precisely how much income inequality has increased amid the COVID-19 crisis, our research indicates a likely amplification of the phenomenon in the coming quarters, especially given governments' reduced ability to distribute social transfers once the consolidation of public finances begins. Individuals working in the most vulnerable segments share many of the same characteristics (an over-representation of certain age groups and gender), and inequality will be further affected in some countries by a marked drop in activity rates. Lower-paying jobs, more likely to be on temporary contracts (with skills that are arguably more easily substitutable than average), are in general more vulnerable to a deterioration of the economic environment. This is illustrated in Chart 8, taking the example of the GFC and subsequent sovereign debt meltdown in Europe, when high income individuals saw their share of total revenue increase in a good half of CEE countries (sometimes markedly). In the countries where the share dropped, the gains of the bottom 20% (displayed in shades of green) did not increase much. Instead, the middle and upper-middle classes gained what the richest lost.

The rise of inequality is likely to have meaningful implications in terms of spending patterns. Indeed, consumers with different levels of income consume different types of goods and services: while low-income individuals usually devote more of their budget to housing and food and utilities, high-income individuals spend more on items of personal care, food outside, and transportation. IHS Markit research suggests that the share of food in CEE consumer expenditures is likely to shrink in the coming years. On the other hand, consumers are expected to devote more of their budget to transportation (personal cars and transport services) as economic development in the region picks up, and as the rise of inequalities favors the individuals in the upper portion of the income distribution.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcentral-europes-consumer-recovery-from-covid19-pandemic.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcentral-europes-consumer-recovery-from-covid19-pandemic.html&text=Central+Europe%27s+consumer+recovery+from+COVID-19+pandemic+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcentral-europes-consumer-recovery-from-covid19-pandemic.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Central Europe's consumer recovery from COVID-19 pandemic | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcentral-europes-consumer-recovery-from-covid19-pandemic.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Central+Europe%27s+consumer+recovery+from+COVID-19+pandemic+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcentral-europes-consumer-recovery-from-covid19-pandemic.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}