Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Apr 15, 2021

CEMAC after COVID-19

- The economic outlook for Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC) countries remains challenging, largely due to uncertainty over containment of the COVID-19 virus pandemic and weak, but recovering, global oil prices.

- Macroeconomic challenges will increase strain on banks' already weak asset quality, while elevated banking exposure to governments represents a key risk to financial stability.

- IHS Markit assesses that future protests in Cameroon and a civil conflict in the Central African Republic (CAR) and insurgents will hinder reform efforts and economic recovery beyond 2021.

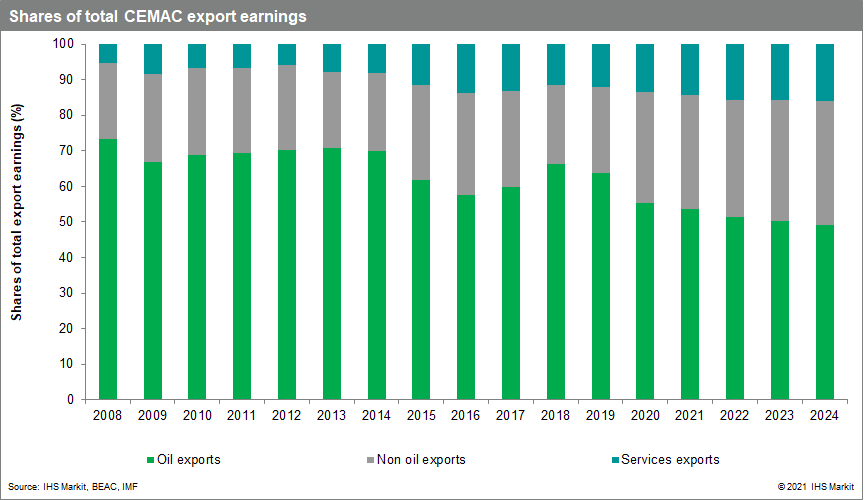

The economic outlook for CEMAC countries - Cameroon, CAR, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon - remains challenging, largely due to uncertainty over containment of the COVID-19 pandemic and weak but recovering global oil prices. IHS Markit expects the CEMAC economy to grow by 3.5% in 2021 and by over 4.0% in 2022. Recovery will be uneven across the region: IHS Markit's latest forecasts project Cameroon's real GDP growth to average 3.5% in 2021 and 2022, and Gabon's growth to average around 2.9%, while Equatorial Guinea is likely to remain in recession given its declining oil production, and CAR, a non-oil producer, is to grow by about 4.5%. We forecast external demand for the CEMAC region's goods and services to strengthen, supported by recovery in the global economy, which we project to expand by about 4.4% in 2021 and 4.2% in 2022. IHS Markit's Dated Brent crude oil price forecast recently improved to about USD67 per barrel in 2021 and we expect CEMAC's important hydrocarbons sector to benefit, providing additional stimulus to growth in the region and permitting upside adjustments to our growth forecasts in future reviews.

Macroeconomic challenges will increase strain on banks' already weak asset quality in CEMAC countries. The region's banking sector has been struggling with poor asset quality since the global decline of oil prices in 2014; non-performing loans rose from 9.1% at end-2014 to 21.3% in June 2020 (when last reported) and we expect impairments to continue rising given the economic challenges caused by the COVID-19 virus pandemic. Additionally, sizeable arrears with government payments are exacerbating the pressure on the sector's already weak asset quality.

The banking sector in the CEMAC bloc is exposed significantly to sovereign solvency, both directly through banks' exposure to sovereign debt, which as of September 2020 amounted to about 15% of total banking assets, and through government ownership of banks - state ownership of banks within the CEMAC region represented about 16% of total banking assets as of September 2020.

Banks are also exposed to sovereign risks indirectly through government arrears to suppliers and service providers who are bank borrowers and depend on government payments to service their bank loans, with delayed state payments thus increasing credit risks for the banking sector. Banks have further exposure through state safety-net arrangements for assets that are protected by explicit and implicit government guarantees.

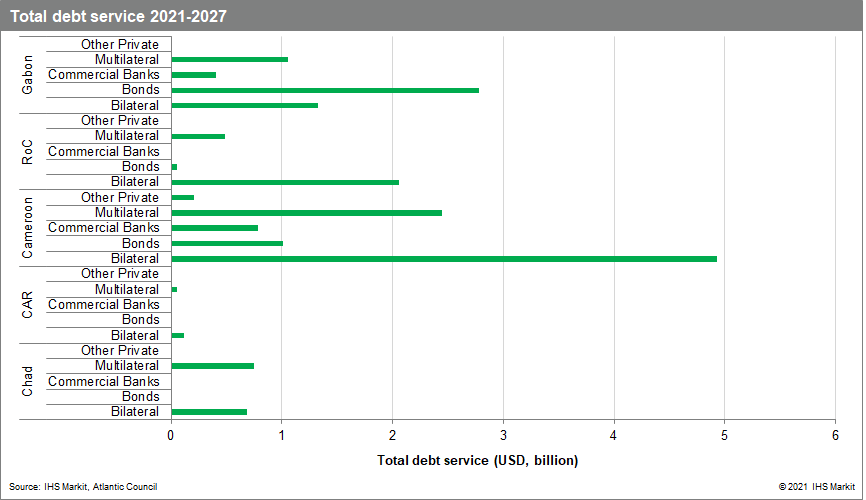

Medium-term debt sustainability requires strong commitment to fiscal consolidation, transparent debt management, effective resource mobilisation, and good governance. Public-sector and publicly guaranteed debt accounts for the largest share of external liabilities in the CEMAC region, with most of this denominated in US dollars. The bulk of the external debt is long-dated and mostly concessional in nature. However, in recent years, CEMAC member countries such as Cameroon, Congo, and Gabon have contracted commercial debt through Eurobonds, while Chad has arranged US dollar-denominated oil-backed loans. Debt vulnerabilities have increased given the weakening of the fiscal positions in the region. In 2020, the region's total public debt rose to an estimated 57% of GDP, from 52% in 2019, with external debt increasing to about 38% of GDP, from 32%. IHS Markit forecasts the CEMAC bloc's debt-to-GDP ratio will remain elevated at above 50% through 2024.

In Cameroon, the sudden death or incapacitation of 88-year-old President Paul Biya would threaten widespread protests and policy paralysis. Power is heavily concentrated in Cameroon's presidency and there is no clear succession plan in place to replace President Biya, who has served for almost 40 years. His official term is due to end in 2025. If he is suddenly unable to continue his duties, the lack of clear succession makes policy paralysis likely until a clear successor takes over, following a succession struggle within the ruling party and among higher military officers. In the country's Anglophone Northwest and Southwest regions, secessionists, largely repressed militarily by Biya's government, would view a power vacuum as an opportunity to obtain greater autonomy, encouraging them to organise large-scale protests. This would strain the capacity of the security forces, making them less able to contain likely medium-scale protests in the Francophone regions' cities of Yaoundé, the capital, and Douala. There, the political opposition would be emboldened by a power vacuum, increasing the probability that it would organise protests demanding fresh elections be held quickly. The protests would imply a high risk of disruption to cargo transportation and trade for weeks and some damage to assets of the ruling party and the security forces.

In CAR, IHS Markit assesses that future protests in the capital, Bangui, and the civil conflict will hinder reform efforts and economic recovery in 2021. Civil war risks have increased in CAR with the formation of the Coalition des patriotes pour le changement (CPC) militia alliance opposed to President Faustin-Archange Touadéra's re-election in December 2020. In January 2021, the CPC took control of several towns on routes leading to Bangui, but the militias would struggle to enter the capital due to the protection and superior weapons strength provided by United Nations and Russian troops, reducing the likelihood of Touadéra's overthrow. Increased commodity prices, which in some cases have tripled due to the impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak, increase the risk of protests in market areas.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcemac-after-covid19.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcemac-after-covid19.html&text=CEMAC+after+COVID-19+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcemac-after-covid19.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=CEMAC after COVID-19 | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcemac-after-covid19.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=CEMAC+after+COVID-19+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcemac-after-covid19.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}