Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Feb 24, 2022

Argentina-IMF deal advances

- The agreement will not demand deep economic adjustment or structural reform, which suggests that some of the main hurdles for doing business in Argentina, such as strict labor laws and the high corporate tax burden, are unlikely to be improved before the 2023 presidential election.

- With the deal, Argentina would avoid defaulting on its IMF liabilities in 2022 but shifts the risk to beyond 2023.

- The more achievable set of policy targets, such as reducing the primary deficit by only 0.5% of GDP in 2022, while continuing to allow central bank funding of government spending (albeit capped at 1% of GDP) are indicators of improving debt and currency positions but are unlikely to prove sufficient to boost confidence in the peso during 2022.

- A final agreement must still be approved by Argentina's Congress, where it is likely to face opposition from the radical Kirchnerist faction of the ruling coalition. Although this is likely to delay the approval, it is unlikely to derail it altogether.

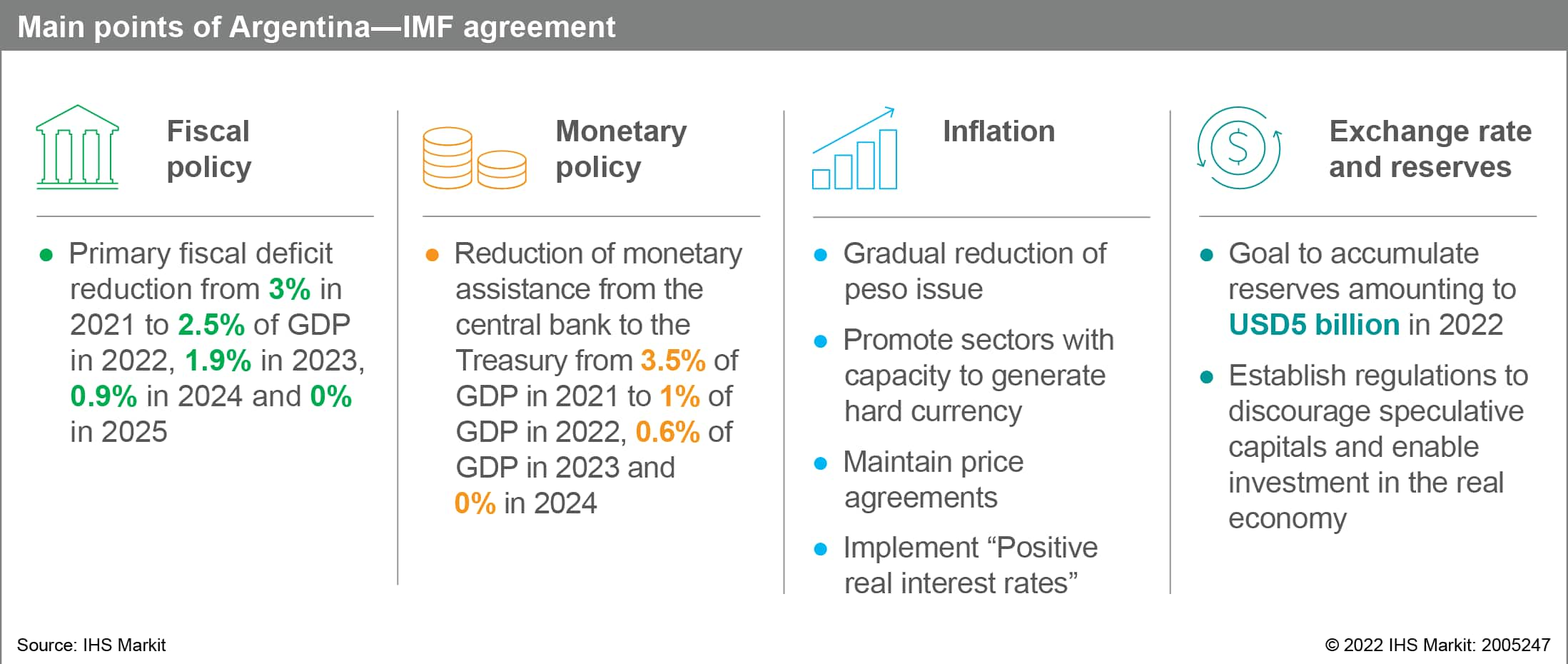

Unlike past IMF conditionality globally, the new 10-year Extended Fund Facility (EFF) worth USD44.5 billion would not demand deep economic adjustment, instead setting gradual primary fiscal-deficit reduction targets from 3% of GDP in 2021 to 2.5% in 2022 and a zero primary deficit in 2025. Neither does it demand structural reform in areas such as labor markets, pensions, or taxes. This suggests that some of the main hurdles for doing business in Argentina, such as strict labor laws and the high corporate tax burden, are unlikely to be improved before the 2023 presidential election, as these would be politically unpopular measures with the electorate.

Default risks

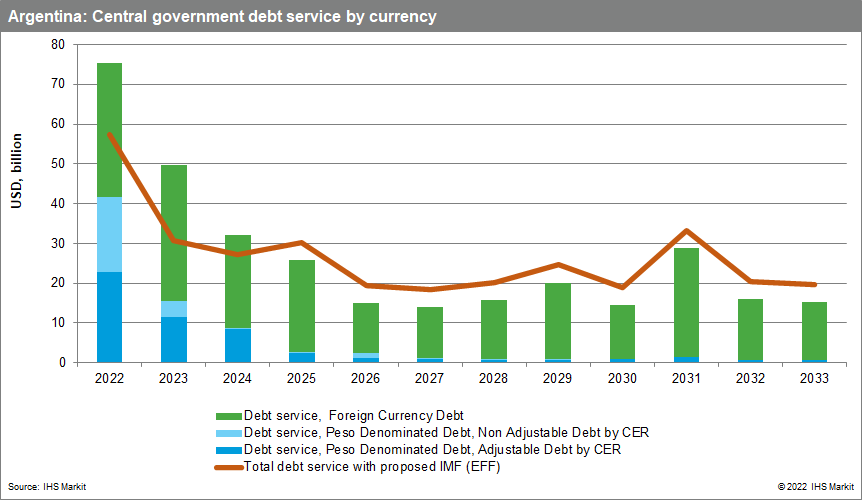

Argentina and the IMF will now work towards reaching a staff-level agreement, while the final deal must be approved by Argentina's Congress and the IMF's Executive Board. If all the stages are completed Argentina would avoid defaulting on its IMF liabilities in 2022, when it faces USD19 billion in repayments. The agreement would allow 4.5-year grace on the new EFF, but its repayment schedule would extend to 2032. During the early period of the facility, the IMF would conduct reviews every three months and could halt disbursements if Argentina fails to meet its commitments regarding fiscal targets, curtailing borrowings from its Central Bank of the Argentine Republic (Banco Central de la República Argentina: BCRA) (printing money to finance state spending) and increasing its foreign reserves. In the event of not meeting the targets set, the IMF would be allowed to introduce new requirements relating to macroeconomic policy, indicating that extended renegotiations remain possible. We assess that the agreement reduces the risk of default in 2022 but shifts it to beyond 2023.

The IMF has elected a cautious but more achievable set of policy targets. For 2022, reducing the primary deficit by only 0.5% of GDP while continuing to allow central bank funding of government spending (albeit capping this at 1% of GDP) are indicators of improving debt and currency positions but are unlikely to prove sufficient to boost confidence in the peso during 2022. Further uncertainty is whether Argentina's monetary policy approach will also change only gradually. One of the IMF's policies to reduce inflation is to set positive real interest rates. However, the real monetary policy rate is currently about -14%. IHS Markit projects high inflation (51.8% in 2022). However, if Argentina complies with the fiscal targets, inflation expectations should decline.

Domestic

challenges

Domestic

challenges

The absence of IMF-led deep economic adjustment includes permitting continued spending on public infrastructure and maintaining targeted social programs. Direct subsidies to the population amounted to nearly 3% of GDP in 2021, and they are likely to remain at approximately the same level in 2022. This will prevent the ruling Peronist coalition Front of All (Frente de Todos: FdT) from alienating its support base ahead of the 2023 election and align with its current policies that seek a gradual reduction in the fiscal deficit, including by reducing utilities' subsidies, which amounted to 3.2% of GDP in 2021. However, this is likely to become a point of contention, as the government estimates that tariffs should increase by 20-35%, while IMF demands are likely to push the increases to 180%, as estimated by sources close to the negotiation quoted in Argentine media. This would delay reaching a staff-level agreement.

Once the agreement is settled, it must be approved by Congress, where is likely to gather enough legislative support from the members of the ruling FdT, loyal to President Fernández, but will find reluctance from the more radical Kirchnerist faction, loyal to the vice-president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (CFK). It is also likely to be backed by the opposition coalition Together for Change (Juntos por el Cambio: JxC). Kirchnerist opposition is likely to delay the agreement but not to derail it altogether.

Labor unions have supported the agreement as it does not propose changes to labor laws. This mitigates the risk of industrial action, including strikes by the powerful truckers' unions, which have the potential to disrupt cargo and transport nationwide for 24-48 hours. However, radical left-wing social organizations will oppose the fiscal tightening trajectory proposed. Such groups are likely to stage localized protests consisting of roadblocks in Buenos Aires city center at 9 de Julio Avenue, the Obelisk, Plaza de Mayo, and near Congress building and entrances to the city, such as the Pueyrredón Bridge, General Paz, and 25 de Mayo.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentinaimf-deal-advances.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentinaimf-deal-advances.html&text=Argentina-IMF+deal+advances+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentinaimf-deal-advances.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Argentina-IMF deal advances | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentinaimf-deal-advances.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Argentina-IMF+deal+advances+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fargentinaimf-deal-advances.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}