Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

May 18, 2021

Why the recent jump in eurozone inflation has not changed the monetary policy outlook

- From December 2020 to April 2021, HICP inflation in the eurozone jumped from -0.3% to 1.6%, the fastest acceleration in the history of the series.

- Energy inflation, partly due to COVID-19-related base effects, has accounted for the bulk of the pick-up, along with other special factors, including VAT changes in Germany and Eurostat's annual reweighting of HICP items.

- Upward pressure on core goods inflation is likely in the coming months but given the large output gap and labour market slack, the risk of significant "second round" effects on eurozone wage and unit labour cost growth will remain low.

- The ECB's near-term priority will continue to be the preservation of very accommodative financial conditions, therefore, evident in the recent faster pace of asset purchases.

The recent surge in US headline and core consumer price inflation rates has intensified the spotlight on reflationary risks and their potential monetary policy implications. For various reasons, the circumstances in the US and eurozone are different and we explain why below, starting with the four key factors which have led to a record pick-up in eurozone inflation over the first four months of this year.

A perfect storm

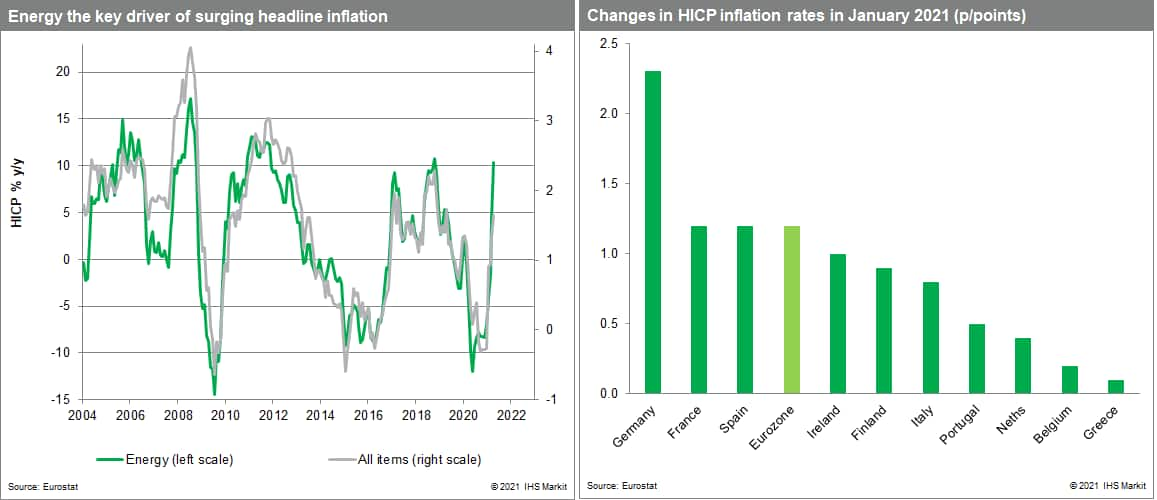

The first, energy inflation, is by far the most important, contributing just over 1.6 of the 1.9 percentage point pick-up in HICP inflation between December 2020 and April 2021 (Chart 1). The rebound in crude oil prices since mid-2020, coupled with recent exceptionally strong base effects stemming from early 2020's COVID-19-driven declines, have pushed up the energy inflation rate by over twenty-two percentage points versus its trough in May 2020.

Second, January 2021 saw a reversal of July 2020's temporary VAT reductions in Germany, coupled with increases in the minimum wage and carbon tax. Combined, these effects are estimated to have boosted German HICP inflation by around 1.3 percentage points and, therefore, eurozone HICP inflation by around 0.4 percentage points. German HICP inflation soared from -0.7% to 1.6% in January as a consequence, the biggest one-month acceleration on record by some distance, and well in excess of the increases in other eurozone member states (Chart 2).

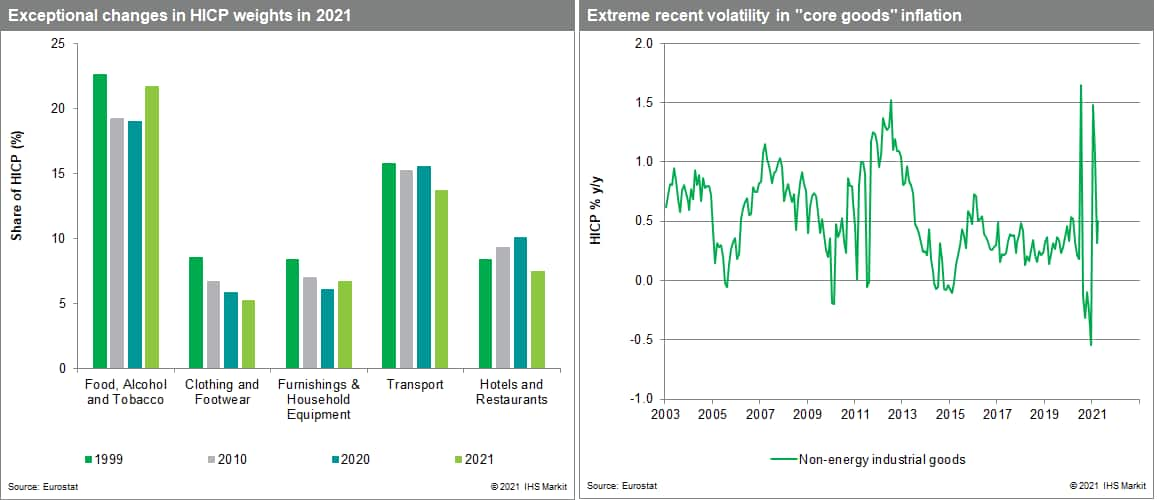

Third, in January each year, eurozone HICP weights are adjusted by Eurostat to reflect changes in consumption patterns. January 2021's adjustments were exceptional, both in scale and in some cases, direction (Chart 3), reflecting the huge impact of COVID-19 on certain types of expenditure. With the weights of some HICP items with relatively high inflation rates having been significantly increased (such as food prices), and vice versa (hotels and restaurants), 2021's weighting adjustments are estimated to have boosted eurozone inflation by 0.3 percentage points in January.

Fourth, January this year also saw an exceptional spike in non-energy industrial goods inflation, from -0.5% to 1.5%, the biggest in the series' history. January's jump echoed a similar surge in July 2020 (Chart 4). In both cases, the cause was COVID-19 disruptions to seasonal price discounting. Discounts (for clothing and footwear, for example) were either postponed or reduced, in anticipation of a future easing of COVID-19 restrictions. In both cases, non-energy industrial goods inflation moderated in subsequent months.

Goods versus services

We note, however, that the subsequent deceleration in non-energy industrial goods inflation this year did not fully reverse January's surge, indicative of goods prices also being pushed up by other factors, including higher commodity prices and supply bottlenecks. These effects will become more pronounced over the coming months.

Eurozone producer price inflation has already shot up since the second half of 2020. While this has been primarily due to energy effects, core PPI inflation (excluding energy prices) has also started to accelerate, with business surveys indicative of more to follow.

Still, the evolution of services prices should be more important in determining longer-run core inflation dynamics, given their higher weight in the core index (around 60%). In contrast to goods prices, prices of services tend to be more sensitive to domestic economic conditions, which have been much more challenging in the eurozone, particularly in the southern member states.

Services prices are also more wage- than commodity-driven and in light of labour market slack, low inflation expectations and the various labour reforms introduced across member states over the past couple of decades (including more localised wage bargaining), wage and unit labour growth rates are unlikely to be sustained at levels typically consistent with 2% HICP inflation.

What goes up…

Given the exceptional combination of factors boosting the eurozone HICP in early 2021, the inflation rate is likely to fall back markedly in early 2022. With oil prices expected to moderate from the second half of this year due to increased supply and less buoyant demand conditions, energy base effects will push sharply downwards on HICP inflation in late 2021 and early 2022.

Base effects related to the German-specific factors highlighted above will also lean down on eurozone inflation in January 2022, though in between times, there will be an estimated 0.8 percentage point boost to German HICP inflation in July 2021 (and a 0.25 percentage point boost to eurozone HICP inflation) from base effects related to the VAT reductions in July the previous year.

Core HICP inflation in the eurozone has picked up since December 2020 but much less than the headline rate. As of April, the rate excluding food, energy, alcohol and tobacco prices stood at just 0.8%, an acceleration of 0.6 percentage points versus December last year, a third of the rise in headline inflation over the same period.

Indeed, core inflation would have remained below 1% were it not for January's special factors (that is, the various changes in Germany and the reweighting of HICP items) and we see a low probability of core inflation rising fast enough over the next year to prevent a sharp fall in headline inflation early in 2022.

Avoiding premature tightening is the ECB's near-term priority

Following its policy meeting on 11 March, the ECB announced that it would step up the pace of its asset purchases under the PEPP, citing concerns over a premature tightening of financing conditions due to rising bond yields and transitory factors driving inflation upwards.

ECB monetary policy cannot directly influence extraneous influences on inflation such as crude oil price gains or VAT increases. As already explained, with the output gap in the eurozone exceptionally wide, slack in the labour market to persist and inflation expectations having been subdued for several years, sustained "second round" effects on wages look rather unlikely in our view.

The ECB will therefore look through higher inflation in the short-term, prioritising the maintenance of very accommodative financial conditions. The ECB's approach reflects an eagerness to avoid a repeat of its prior policy missteps, notably the premature unwinding of monetary accommodation back in 2011 which contributed to the subsequent escalation of the eurozone crisis.

Its ongoing monetary policy strategy review is also significant. We expect it to conclude with a shift to an explicitly symmetrical inflation aim (of 2%), coupled with tolerance of modest inflation overshoots following long periods of undershooting.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhy-eurozone-inflation-has-not-changed-policy.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhy-eurozone-inflation-has-not-changed-policy.html&text=Why+the+recent+jump+in+eurozone+inflation+has+not+changed+the+monetary+policy+outlook+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhy-eurozone-inflation-has-not-changed-policy.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Why the recent jump in eurozone inflation has not changed the monetary policy outlook | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhy-eurozone-inflation-has-not-changed-policy.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Why+the+recent+jump+in+eurozone+inflation+has+not+changed+the+monetary+policy+outlook+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fwhy-eurozone-inflation-has-not-changed-policy.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}