Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Feb 21, 2022

The impact of civil unrest on Port Sudan

Trade and transport operations through and around ports in Sudan's Red Sea state, including Port Sudan, have been disrupted regularly by political violence and protests since 2019, driven primarily by inter-communal rivalries and evolving power dynamics across Eastern Sudan. In September-October 2021, Beja tribal leaders blocked access to key infrastructure serving Red Sea ports, including Port Sudan, with likely support from elements in the military leadership frustrated with their since-deposed civilian counterparts.

Separately, a military coup on 25 October 2021 has left Sudan at its highest level of political instability since the ousting of Omar al-Bashir as president in 2019. The coup has left the military in de facto control, supported by east Sudan's Beja tribal group, but without international endorsement, legitimacy, or consensus backing. The Beja tribes lifted the blockade on 1 November 2021 as a show of support for the October coup.

Importance of Port Sudan

Located in one of the world's most important maritime passages, connecting the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea, Port Sudan is Sudan's largest port and main commercial and trade hub housing critical oil export terminals. Sudan's foreign trade transiting its eastern states amounts to approximately USD11 billion yearly (30% of GDP), representing one of the state's main sources of revenue and employment.

Port Sudan is also a commercial sea gateway for neighboring landlocked countries, particularly South Sudan, as well as Chad and the Central African Republic, which means that any significant disruption at the port is likely to affect these countries' trade transiting Sudan. Any renewed blockades are likely to exacerbate already acute shortages of key goods and commodities, and disrupt exports, including for neighboring countries.

Impact of disruption

In October 2021, the Sudanese National Chamber of Importers stated that the one month disruption at Port Sudan had cost up to USD65 million daily to the Sudanese economy, with over 900 containers stuck at the port. Additionally, highway blockades resulted in the halting of around 3,000 trucks, causing losses of up to USD2 million daily.

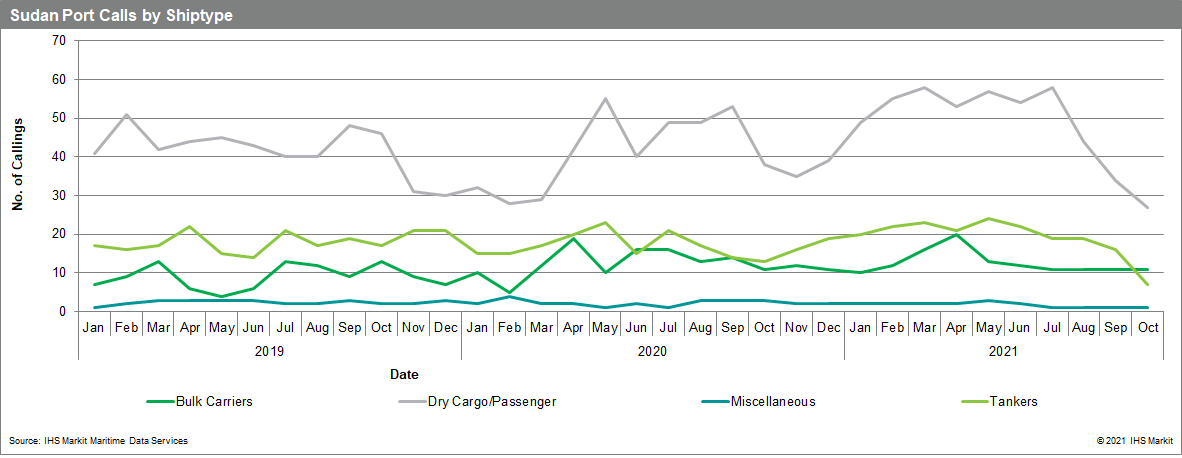

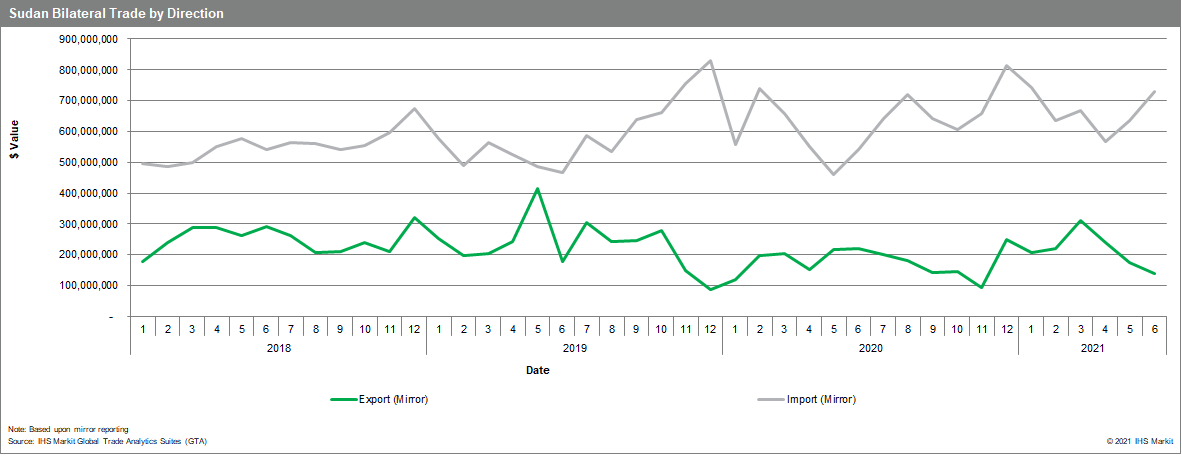

IHS Markit assesses that rapid declines in Sudan's exports and port calls in the second half of 2021 were caused by disruption resulting from the protest activity and blockades in Eastern Sudan, especially in and around Port Sudan. IHS Markit's maritime data shows a significant decrease in port calls in the second half of 2021, with a more pronounced decline since September, particularly affecting dry cargo, followed by oil tankers and bulk carriers.

Given Sudan's very high dependence on imports, any disruption to imports is likely to exacerbate already acute shortages of key goods and commodities, such as fuel, wheat, and medicines. This is also important in relation to Sudan, given that widespread shortages of bread and fuel in 2018 were primary drivers of the nationwide mass protests that ultimately led to President Bashir's ousting in 2019.

Vulnerability of Port Sudan

The increased levels of uncertainty due to the political changes following the October 2021 coup are likely to result in rival tribal groups seeking to assert their respective interests and secure vital resources, including land and port employment opportunities. The Beja tribes are likely to use Port Sudan as a vulnerable point, on which to apply pressure to gain concessions from the government and their rivals.

Additionally, Port Sudan has a long history of labor unrest, especially given that job security is precarious. The port is the largest employer in Red Sea state, drawing its labor force from a wide area. Port workers demand regularly higher salaries and the payment of arrears and strongly oppose any government attempts to privatize or modernize the port (through automation), fearing that this would result in lay-offs. The automation of port activities, using newly acquired machinery such as trailers, would be particularly problematic for the Beni Amer/Beja groups, who traditionally have handled these port activities.

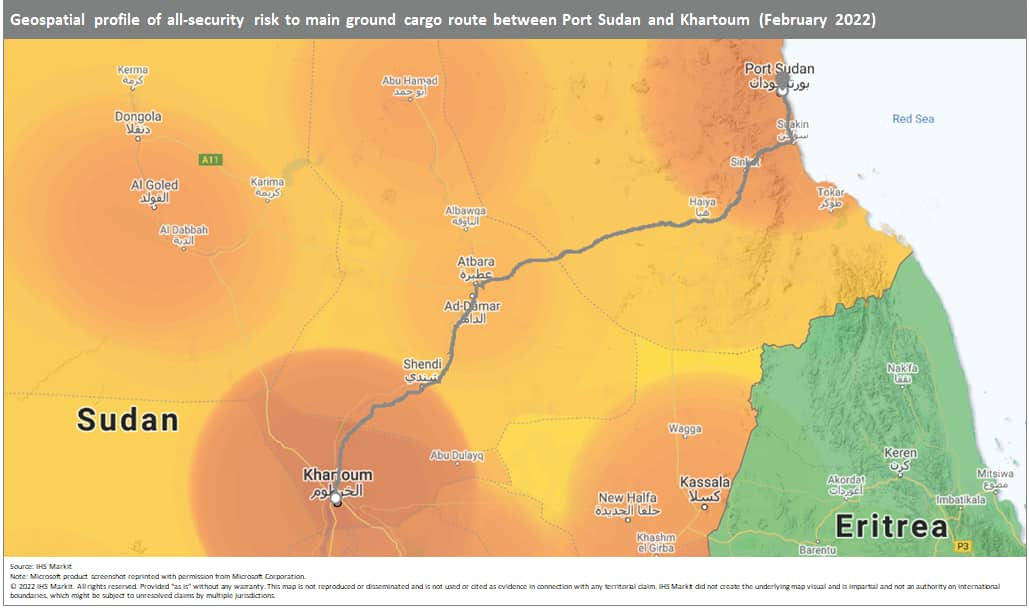

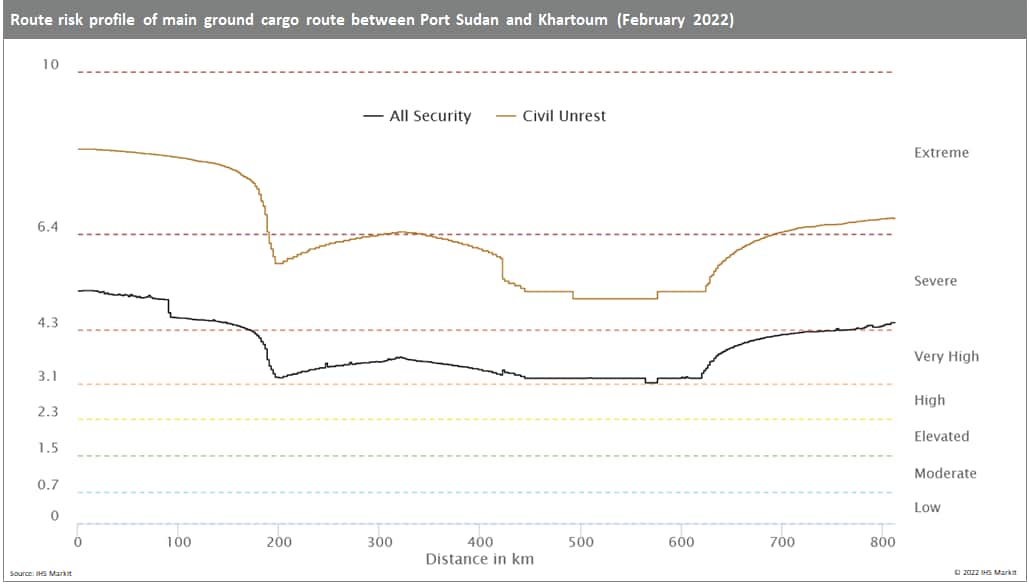

Pro-Beja supporters have also blocked the primary national road linking the Red Sea coast to Khartoum and the rest of the country at several points (see route risk profile below). This includes Sinkat, where protesters have previously blocked the road on both sides using hundreds of trucks and public transport vehicles. These protests usually last up to a few hours in each instance but can last up to a week. Civil unrest in other locations along this road, such as Atbara, Ad-Daman, and Shendi, is also likely to cause similar disruption to cargo, although looting or damage to cargo is unlikely.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fthe-impact-of-civil-unrest-on-port-sudan.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fthe-impact-of-civil-unrest-on-port-sudan.html&text=The+impact+of+civil+unrest+on+Port+Sudan+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fthe-impact-of-civil-unrest-on-port-sudan.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=The impact of civil unrest on Port Sudan | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fthe-impact-of-civil-unrest-on-port-sudan.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=The+impact+of+civil+unrest+on+Port+Sudan+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fthe-impact-of-civil-unrest-on-port-sudan.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}