Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Mar 09, 2021

Terrorism in the Philippines: Examining the data and what to expect in the coming years

The communist insurgency in the Philippines has been ongoing since 1969 and shows no sign of abating. On the contrary, recent statements by the exiled founder and chairman of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), Jose Maria Sison, suggests that the party's armed wing, the New People's Army (NPA), will seek to expand its attacks to major cities from rural areas where the rebels operate.

In the south of the country, the Moro-Islamist insurgency continues despite the establishment of an autonomous region in the Muslim-majority parts of Mindanao in 2019, and the heavy losses suffered by Islamist militant groups that had pledged loyalty to the Islamic State (IS) during and immediately after the five-month siege of Marawi City in 2017.

Analytics using metadata from a large set of security incidents help to shed light on the contrasting nature of these twin pillars of terrorism risk in the Philippines, and aid analysts to better forecast the future risk environment.

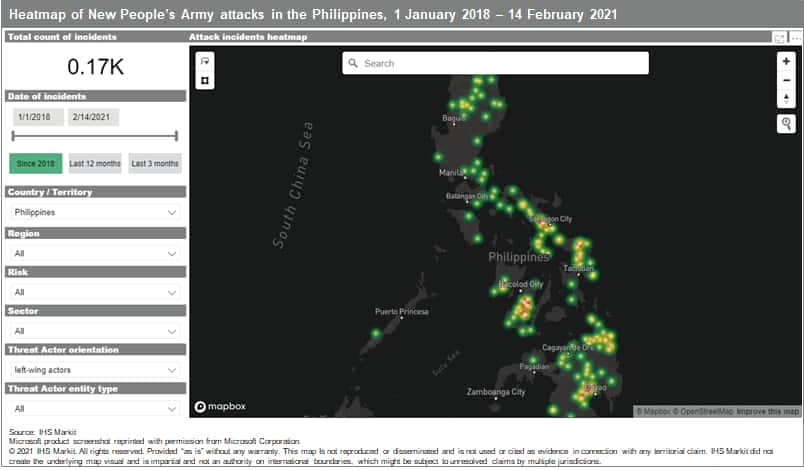

Attacks geospatial footprint: New People's Army

A quick glance at our heat map of attack incidents by non-state actors dating back to 2018 shows a broad operational footprint of NPA attacks across the three geographical areas of the Philippines: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao.

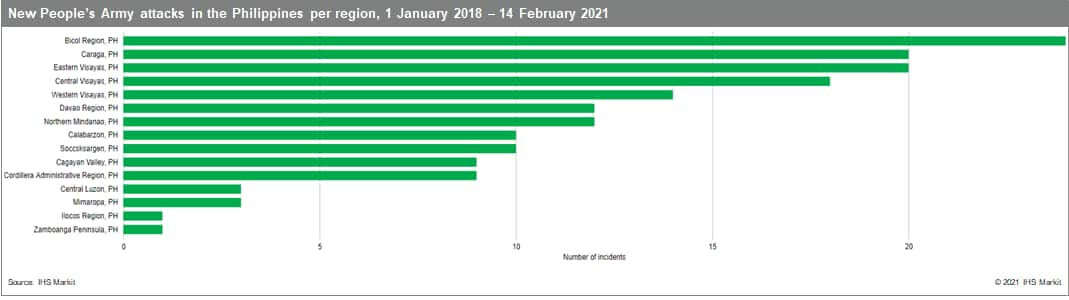

A region-by-region breakdown graph shows NPA attacks in 15 out of the Philippines' 17 administrative regions, with the exception of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) and Metro Manila. Bicol (southern Luzon) has seen the most NPA attacks since 2018, with comparatively large concentrations (>10) in various regions of the Visayas, as well as regions of the Mindanao area such as Caraga, Davao, and Northern Mindanao.

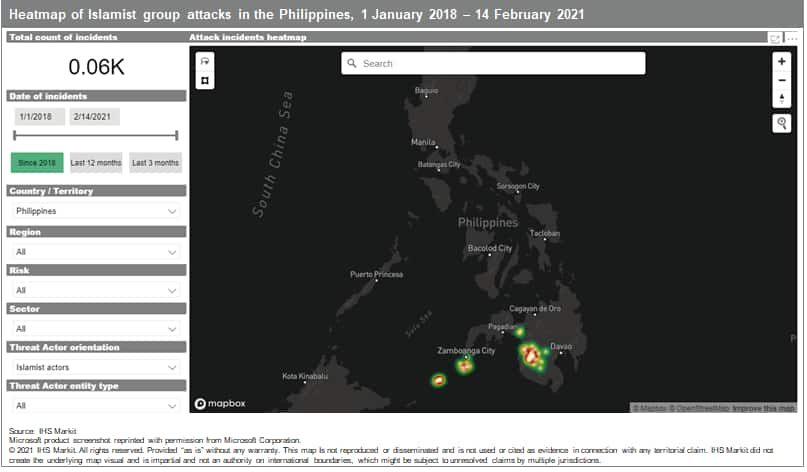

Attacks geospatial footprint: Moro-Islamist insurgency

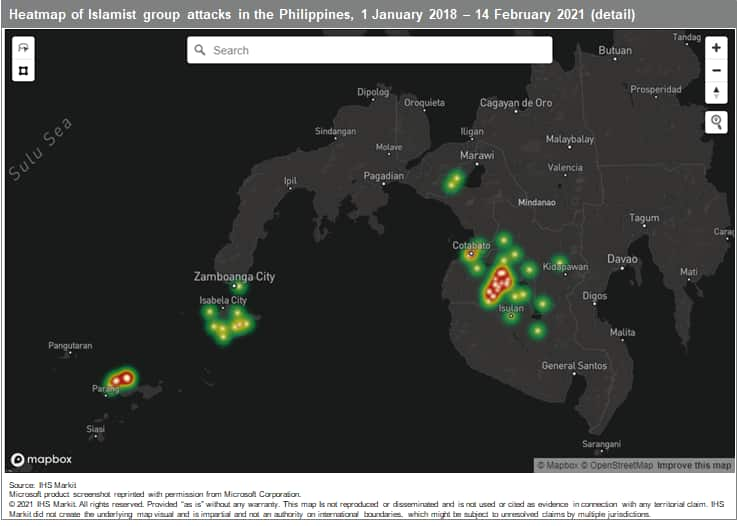

In contrast to the NPA's very broad spread of attacks across the Philippines, the Moro-Islamist insurgency is much more localised in the southern Mindanao area and involves numerous organisations, factions, and networks. Following the 2014 peace agreement between the government and the main Moro-Islamist organisation, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the two sides agreed on a devolved authority called the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, which was established in 2019 and covers the Muslim majority areas of western Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago. However, other Islamist groups continue to wage war against the Philippine state, most notably demonstrated in the five-month battle of Marawi City in 2017 which involved Filipino groups that had pledged loyalty to the IS, such as the Isnilon Hapilon faction of the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), and the Maute Group, aided by foreign IS fighters. Although Hapilon and the Maute brothers were killed in Marawi, the ASG and other Moro-Islamist groups continue to pose a security threat.

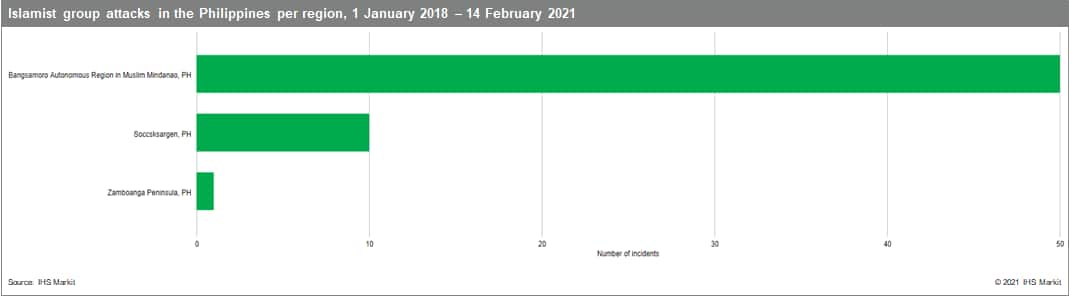

Our data since 2018 shows that attacks by groups such as the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), the ASG, the Moro National Liberation Front and Dawlah Islamiya (when used by the Philippine military and then quoted in the domestic media, this refers to BIFF faction allied to IS). These attacks are confined to the south and west of Mindanao as well as the Sulu archipelago, a chain of islands that leads to the Philippines' maritime border with Malaysia. Specifically, the Mindanao regions of Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao, Soccsksargen, and the Zamboanga Peninsula.

Modus operandi: New People's Army

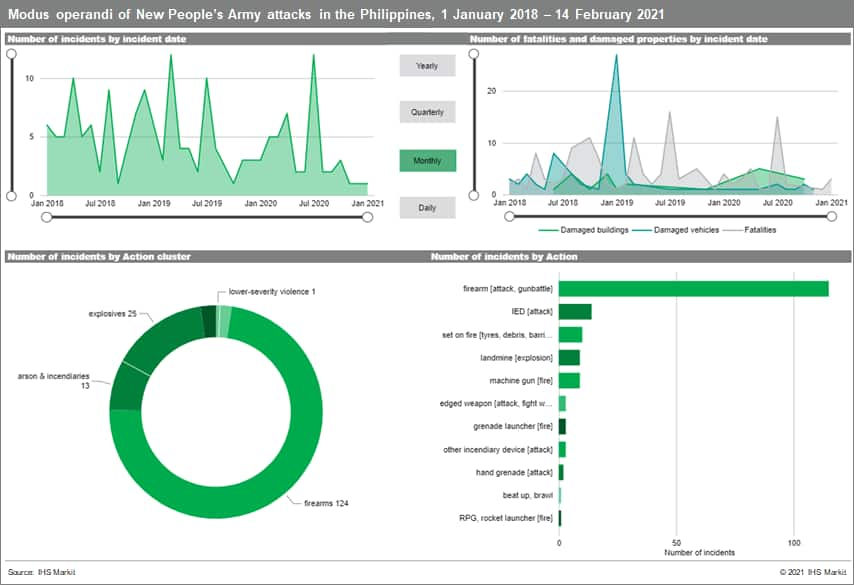

Our NPA incident data shows a propensity for small arms use in its operations (73%), with explosives (primarily Improvised Explosive Devices and landmines) used in a comparatively much smaller (15%) proportion of attacks.

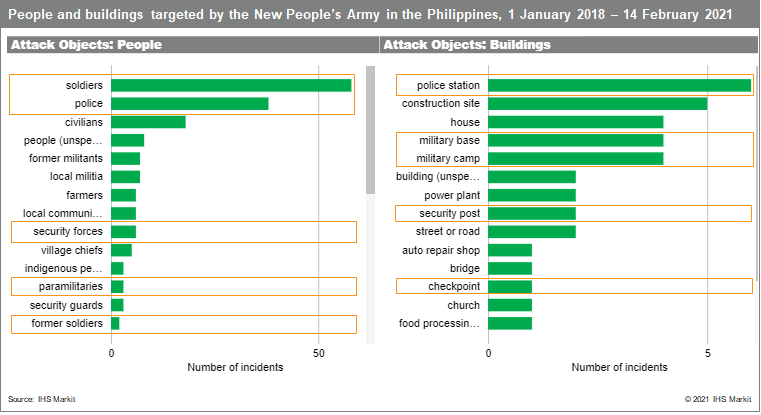

NPA units typically ambush Philippine security forces or attack small police and military posts. This reflects the ideological aim of the CPP-NPA to weaken the Philippine state, as a state towards installing a communist political system.

Our data also shows that the targeting of civilians by the NPA is also common. Victims include local government officials or community leaders that the NPA accuses of collaborating with government forces, of committing alleged "crimes" against the people, or refusing to collaborate with the NPA.

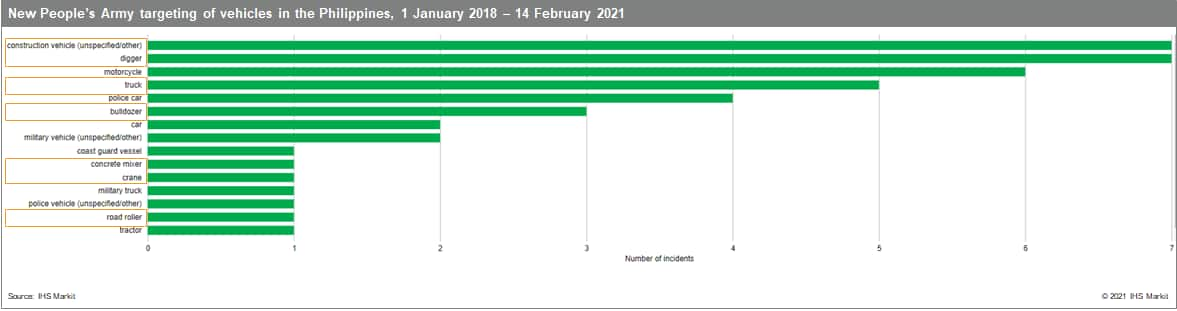

However, a revolution cannot live on ideology alone. The policy of weakening security forces in certain areas also serves the dual purpose of creating a space in which the NPA can extort what it deems 'revolutionary taxes' from civilians, politicians, and businesses. A breakdown of the vehicles damaged by the NPA shows a clear focus on those often used in commercial / construction projects, such as diggers, bulldozers, and trucks. Likewise, the graph above shows conduction sites as the second most targeted asset set after police stations - even more so than military bases and camps. The vast majority of these incidents are highly likely to be as a result of a refusal to pay extortion, with small arms and arson attacks a common form of reprisal or warning - yet falling short of seeking to cause such extensive damage as to make the project untenable (and thus unable to be targeted for further extortion revenue).

Sectors most impacted tend to include mining, agribusiness, forestry, construction, telecoms, and power.

There is no reliable, independent, estimate of the cost of NPA extortion on businesses. However, the Philippine Army's military command that covers eastern Mindanao, Eastmincom, estimated that in 2017 the NPA collected PHP2.48 billion (USD49.87mn) from mining and agribusiness companies that operate in the provinces under its command.

Modus operandi: Moro-Islamist insurgency

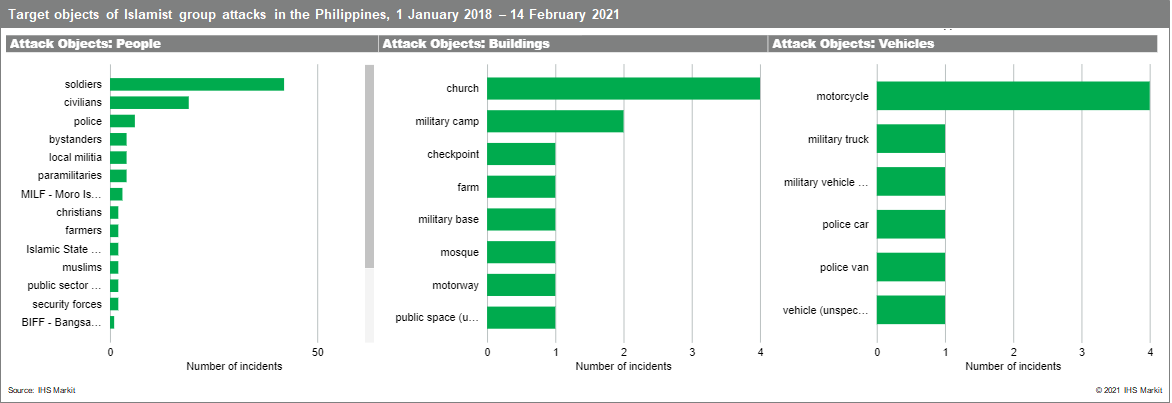

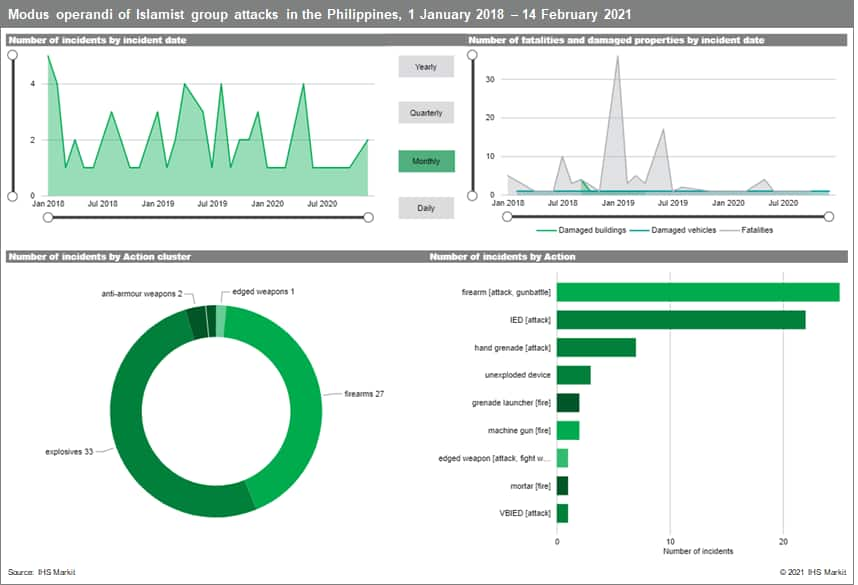

Our data on attacks perpetrated by Islamist groups reflects the fractured nature of the Moro-Islamist insurgency in the Philippines. As with the NPA, soldiers and police officers are frequently targeted by Islamist groups in their fight against the Philippine state. However, MILF (dissidents who refused to join the peace process), IS and BIFF are also themselves targeted by rival Islamist groups, often driven by differing stances on whether to engage in peace negotiations with the Philippine government.

MILF was founded by MNLF leaders who were opposed to a peace deal that led to the establishment of the now defunct Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao in 1990. BIFF was founded in 2008 by MILF members calling for independence instead of the devolved government as expressed in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao. BIFF itself subsequently split into three groups, including one that allies itself with IS.

All of the incidents in our data set of Islamist groups targeting vehicles were directed against security forces or pro-government paramilitary militia members (including ambushes against those traveling by motorcycle). This contrasts with the NPA's extortion-related attacks on commercial vehicles. This reflects the focus on kidnap-for-ransom, as opposed to extortion, for funding - mostly notably by the ASG in the southern Philippines, the Malaysian state of Sabah and of sailors in the waters in between. That said, no single data set alone will ever provide the complete security picture. Although such incidents may not get reported frequently in open source new and social media outlets, our human sources int e southern Philippines confirm that IS-affiliated groups in Mindanao are also known to carry out extortion, larceny, and trafficking of arms and drugs; the Mautes and their extended families ran a mix of black market and legitimate businesses, while the BIFF are known to rustle cattle and seize farmland.

The targeting of churches, most notably the suicide attack on Jolo cathedral in 2019 which killed 20 civilians, reflects the rising influence of IS in the tactics of Islamist insurgents, particularly the ASG, in the Philippines. Suicide attacks are relatively recent and rare in the ASG's three-decade insurgency; the first occurred in 2018 against a military checkpoint and there was another in August 2020. The arrests of nine women in February 2021, including three daughters of a deceased ASG leader, on charges of planning suicide bombing suggests this tactic will continue to be used.

It is noteworthy that Islamist groups in the Philippines already tend to use explosives in a comparatively higher proportion of attacks than the leftist NPA - 52% compared with 15%.

What next?

Moro-Islamist insurgency

The chief of the MILF-led Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) - the interim government of the BARMM - Ahod Ebrahim, claimed in January 2021 that 900 fighters of the two BIFF factions that are not aligned with IS were in talks with the transitional government to rejoin the MILF. A successful conclusion to the talks would mean a considerable weakening of the insurgency on mainland Mindanao where BIFF operates.

The BTA is asking the government to extend its interim authority, which is due to end 2022, by a further three years on the grounds that it has not yet been able to complete the legally-mandated milestones that established the BARMM, such as the decommissioning of fighters and the establishment of a police force. An extension would mean a postponement to the elections due in 2022. The plan enjoys popular support in mainland Mindanao but is opposed by political leaders in Sulu province. A key indicator of whether the extension will be granted - and thus whether the broader MILF peace process and the subsequent reduction in violence it heralded - will be President Rodrigo Duterte potential designation of the related bills (at the time of writing, four in the House of Representatives and two in the Senate) as priority legislation.

However, there is little indication that the ASG in the Sulu archipelago will be pacified in the remainder of Duterte's term, which runs to June 2022. Duterte has sought to defeat the ASG militarily by deploying more troops but the ASG appears to be able to continue to inflict casualties on the Philippine military in armed confrontations and suicide attacks.

New People's Army

Peace negotiations between the government and the CPP-NPA collapsed in February 2017 and, having initially vacillated whether to restart them, President Rodrigo Duterte has in the past year ruled out any prospect of negotiations for the remainder of his term.

In fact, the government's attitude towards the CPP-NPA is hardening: it designated the group as a terrorist organisation in December 2020; it is taking steps to ban civil society groups which Duterte alleges harbour covert communists from having representation in Congress; and it is imposing stricter surveillance of alleged communist students and staff at universities. In response, the NPA has threatened to expand its operations to the cities.

In a statement in December 2020, Jose Maria Sison warned that the NPA would revive its urban assassination teams known as Special Partisan Units (Sparus) or 'Sparrow units' that were last active in the early 1990s to attack groups and assassinate individuals accused of 'crimes against the people'. Sison justified the revival of the Sparrows on the increasing number of 'Oplan Tokhang' incidents and other extrajudicial killings of communists and left-wing activists, allegedly by security forces and paramilitary units. Any increase in urban assassinations of government officials and security personnel would be most likely in Manila, Cebu City, and Davao City, as happened in the 1980s and early 1990s. The NPA's doctrine and expertise indicate that the majority of such operations would probably be limited to their intended targets as opposed to posing significant collateral risks to bystanders, for example via the use of IEDs. However, there are evidently inherent risks of stray bullets as a result of the likely modus operandi of gunmen on motorbikes targeting vehicles in traffic, shootings in workplaces (for example political party offices) or at restaurants, or if bodyguards return fire.

Nevertheless, the CPP-NPA leadership's adherence to Maoist principles means that the reactivation of its urban assassination operations will likely be a limited tactical move rather than a strategic shift away from the primacy of rural insurgency. As such, it is highly unlikely in the foreseeable future to deploy a large number of guerrillas to attack and occupy a town or city in the manner of the occupation of Marawi by Islamist insurgents in 2017. In his post on the CPP-NPA website explaining his reasons to revive operations in the cities, Sison also reiterated his intention to continue to target major mining, agribusiness plantation and logging companies.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fterrorism-philippines-examining-data.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fterrorism-philippines-examining-data.html&text=Terrorism+in+the+Philippines%3a+Examining+the+data+and+what+to+expect+in+the+coming+years++%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fterrorism-philippines-examining-data.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Terrorism in the Philippines: Examining the data and what to expect in the coming years | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fterrorism-philippines-examining-data.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Terrorism+in+the+Philippines%3a+Examining+the+data+and+what+to+expect+in+the+coming+years++%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fterrorism-philippines-examining-data.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}