Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Dec 18, 2020

Terrorism in Egypt: Examining the data and what to expect in 2021

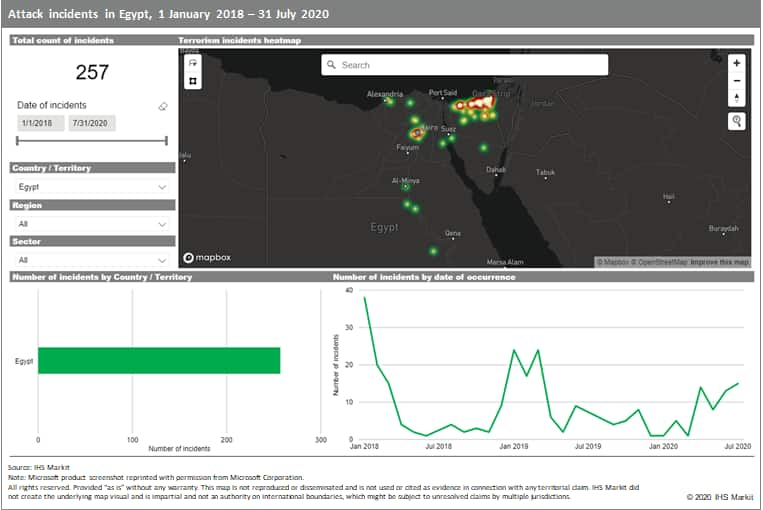

The pattern of terrorist activity in Egypt tells a consistent story of attacks concentrated in northern Sinai (Shamal Sina' governate) and prone to peaks and troughs closely aligned to security force deployments. Whilst this suggests security forces are effective in tackling the threat when deployed, the fact that they do not have the capacity to remain on permanent deployment in northern Sinai means the threat will re-emerge as deployments end. Looking out to 2021, the deployment of the 2nd and 3rd Field Armies is likely to continue without significant planned restructuring of the field command. As a result, we expect to see a continuation of regular attacks against the armed forces and its material assets in northern Sinai. The data shows that attacks primarily affect military convoys and as a result the risk of Improvised Explosive Device (IED) attacks along the coastal highway, particularly between Sheikh Zuweid and El Arish, is likely to remain high.

Why northern Sinai?

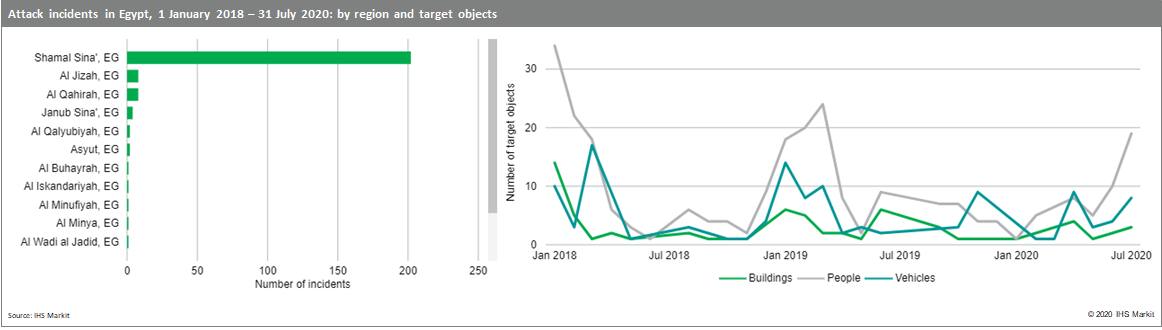

The main epicentre of terrorist incidents in Egypt (204, or 78% of those recorded between 2018 and mid-2020), continues to be northern Sinai (Shamal Sina' governate), where an Islamic State insurgency (calling itself 'Wilayat Sinai', or 'Sinai Province') has been ongoing since 2014. Notable though is the relative failure of the group to expand its area of operations into southern Sinai (Janub Sina' governorate; just 4 incidents recorded). Security along the border of these governates was improved after the bombing of a Russian passenger jet in Sharm El Sheikh in 2015 with more police checkpoints, and subsequent incidents have involved individuals crossing into southern Sinai before being intercepted by security forces, as occurred near Ras Sidr in April 2019. The tourist resort of Sharm El Sheikh itself has had a composite concrete and chain-link barrier built around it. Islamic State has been largely unsuccessful in building a foothold west of the Suez Canal. In particular, an attack on a North Sinai mosque in 2017 that killed over 300 civilians failed to have the likely intended effect of widening the insurgency and dividing the country's religious groups. That attack, largely perceived by mainstream Sunnis and militant Islamists alike as an immoral assault on Muslims, alienated potential tribal recruits in Sinai and feed recruitment to rival jihadist groups operating west of the Suez Canal.

The overall number of attack incidents dropped considerably in the months after January 2018, most likely as a result of Operation Comprehensive Sinai - when the army increased the size of its forces deployed in North Sinai. The trend for 2020 shows an increasing frequency of incidents from March onwards. Behind this is a shift in target areas for Islamic State in Sinai; the group moved further west within North Sinai than had previously been usual, as evidenced when militants on 21 July attacked an Egyptian army camp in the village of Rabaa, 23 km west of the town of Bir al-Abd and occupied at least four villages.

What types of attacks - who is targeted and how?

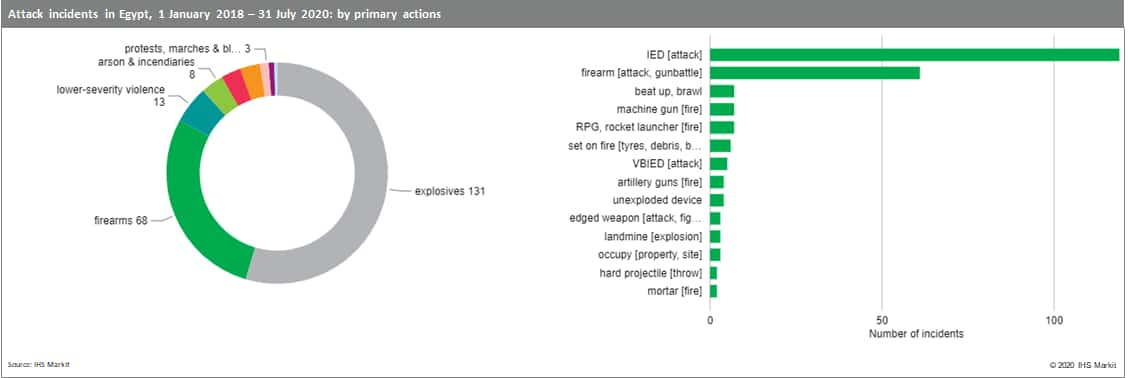

There were almost as many IED attacks as all other attack types combined. This reflects the capability of Wilayat Sinai militants to actively target security force convoys travelling along the North Sinai coastal highway, particularly between Sheikh Zuweid and El Arish, the two urban centres where they are most active. This also highlights the ongoing failure of the Egyptian military to incorporate effective electronic countermeasures into military convoys - probably as a result of the high cost and relatively poor training of most of the conscript soldiers deployed in Sinai.

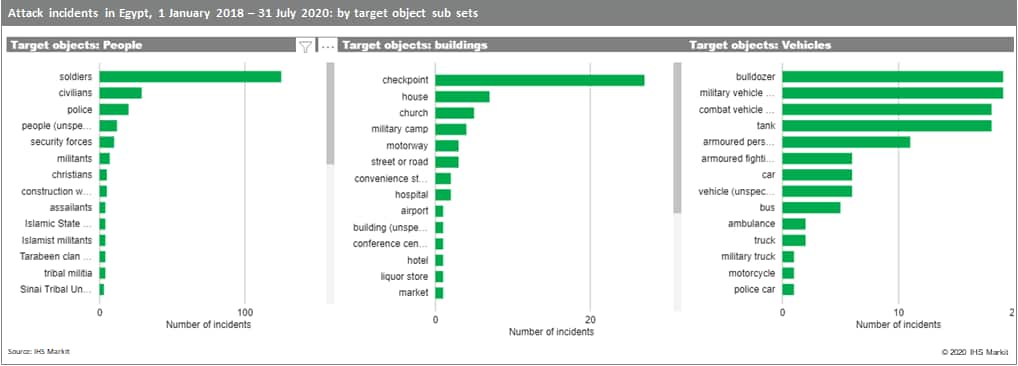

The data shows that security forces are the top target set in terms of people. This is also reflected in checkpoints and military camps being the most common and fourth most common type of building targeted, respectively. Notably, while civilians represent the second most frequent category of human target, they represent approximately one third of the number of soldiers targeted. This proportional difference probably illustrates both the failure of terror groups across Egypt to carry out consistent or mass casualty attacks in Egypt's cities since late 2017. Those civilians that are targeted are almost certainly disproportionately from North Sinai.

Bulldozers represent the joint most common type of vehicle targeted in Egypt, along with general military vehicles. This illustrates the extensive military engineering presence in North Sinai, where military bulldozers are used both in an industrial capacity by military-owned businesses located in Sinai, in ongoing construction efforts, and in the mass demolition of civilian housing in areas suspected of being infiltrated by Wilayat Sinai. The bulldozers are frequently damaged by IED blasts as they travel in convoy between North Sinai's towns and military bases.

What next?

Despite the long-term deployment of the Egyptian military in Sinai, we assesses that there has been little indication of qualitative improvement in the Egyptian military's counter-insurgency strategy over the course of 2020 that would suggest a significant reduction in operations for the Islamic State in Sinai. Although militant capabilities have not returned to the levels of sophistication seen from 2014-16, the group has shown it still retains high level capabilities. At least three vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIEDs) were used in an attack on a military checkpoint in August 2020; IHS Markit data shows that this was the first time they had been used in northern Sinai since August 2018. Additionally, one of the militants detonated an explosive vest - the first recorded use of such equipment since October 2019.

The poor capability training and equipment of Egyptian conscript troops has likely contributed to the operational successes of Wilayat Sinai militants. Poor co-ordination between the Egyptian Second and Third Field Armies in Sinai is not expected to improve without significant reshuffling of senior military personnel and the introduction of new doctrine and tactics.

Islamic State cells will probably attempt to carry out low-capability attacks outside of the Sinai Peninsula, involving shootings, suicide bombings, or vehicle rammings. Targets in Cairo and Alexandria are likely to be a priority for this but will probably remain largely aspirational with security forces likely at highest risk. Such attacks, if they take place, are likely to be unsophisticated and targeting security forces, involving shooting attacks, primitive IEDs, and thrown incendiaries on isolated checkpoints and police convoys in the poorer parts of Egypt's urban areas, particularly in Cairo's Shubra El-Kheima, Helwan, and Imbaba districts. Coptic Christian targets are also likely to remain a priority, but are likely to benefit from greater surveillance and security protection.

A resurgence of militant activity to the west of the Sinai Peninsula would increase the risk of attacks against shipping in the Suez Canal, and the Egypt Gas Pipeline (operated by a consortium including Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company and Egyptian Natural Gas Company). The canal is policed by the military with checkpoints every 20 km monitored by helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft. Although Wilayat Sinai has demonstrated possession and the capability to use advanced weapons such as anti-tank guided missiles or man-portable air-defence systems - most recently in an anti-tank missile attack on a grounded helicopter at El Arish Airport in 2017 - the use of such systems in Sinai has dropped off in recent years. The main damage done by such attacks would probably be psychological, eroding commercial confidence in the adequacy of security measures and incurring additional security costs, even when attacks are unsuccessful, and they would be unlikely to significantly damage a major vessel. Such an attack would be unlikely to result in long-term re-routing of vessels around Africa but would almost certainly raise the cost of insuring Canal transit.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fterrorism-egypt-examining-data-what-to-expect-2021.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fterrorism-egypt-examining-data-what-to-expect-2021.html&text=Terrorism+in+Egypt%3a+Examining+the+data+and+what+to+expect+in+2021+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fterrorism-egypt-examining-data-what-to-expect-2021.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Terrorism in Egypt: Examining the data and what to expect in 2021 | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fterrorism-egypt-examining-data-what-to-expect-2021.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Terrorism+in+Egypt%3a+Examining+the+data+and+what+to+expect+in+2021+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fterrorism-egypt-examining-data-what-to-expect-2021.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}