Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Oct 18, 2021

Supply chain disruptions in Central Europe

- Even if the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) virus pandemic does not trigger further country-wide restrictions, optimism regarding the short-term outlook for the Central and Eastern European (CEE) region is diminishing, as countries face shortages and delays along the supply chain.

- The logistics crunch has contributed to a surge in producer prices, further affected by rising energy and transportation costs, as well as a shortage of skilled labour.

- The shortages are becoming more widespread across sectors with the most broad-based shortages felt in motor vehicle manufacturing, computer and electronics, as well as rubber and plastics.

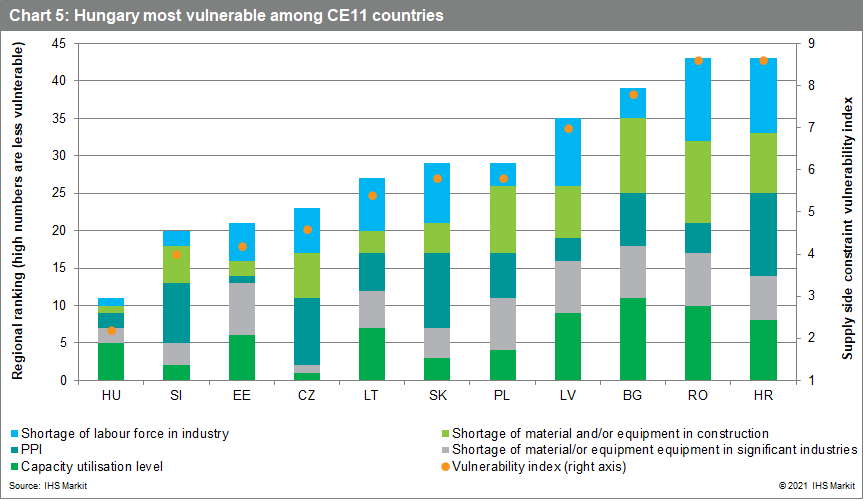

- IHS Markit's vulnerability index shows that Hungary, Slovenia, Estonia, and Czechia are facing higher supply-side constraints than other countries.

- Although supply-side constraints pose a negative risk for short-term manufacturing growth, automation and reshoring provide opportunities for CEE countries over the medium to long term as they find a new role amid pandemic-induced structural changes in supply chains.

Supply-side constraints and labour shortages are rising on many fronts

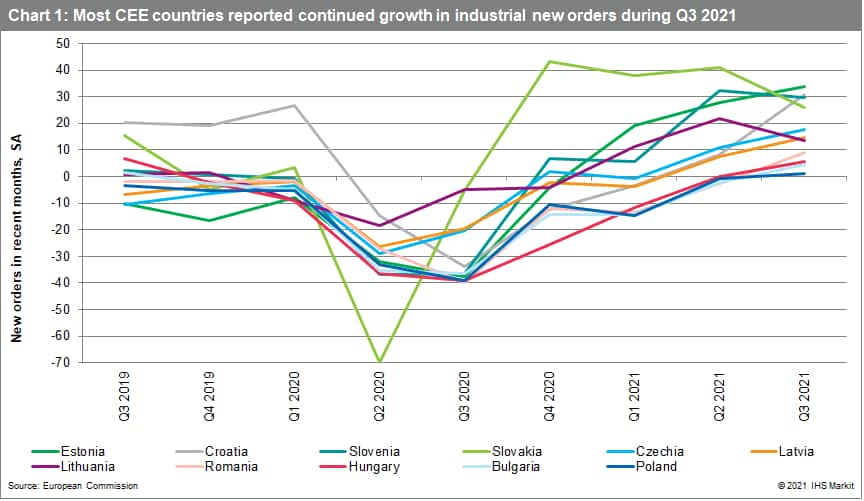

Amid strong foreign demand, European Commission surveys indicate that new industrial orders continued to rise in most Central European countries during the third quarter, remaining at historically high levels in much of the region (see Chart 1). Nevertheless, a recovery of new industrial orders does not automatically translate to a strong rebound in manufacturing production. Indeed, production is likely to be limited over the short term owing to rising supply-side constraints.

During the course of 2021, shortages and delays along the supply chain have already been notable in regard to microchips and semiconductors used in car manufacturing and electronics. Globally, the automotive sector has been hit the hardest, resulting in temporary shutdowns at car plants since April. Other goods that have been affected include metals, rubber, plastics, lumber, and paper.

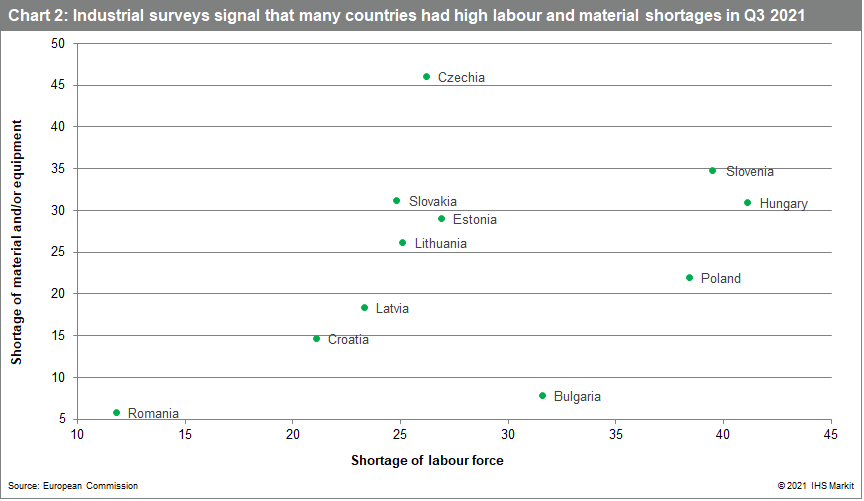

Third-quarter industrial surveys indicate that many countries in the region have been facing high shortages of materials and equipment as well as labour (see Chart 2), with Romania being the main exception. Skilled labour shortages are not a new phenomenon in Central Europe, and compared with historical levels, shortages of labour in the industrial sector have increased less than shortages of material and equipment, which have reached historical highs in a number of countries.

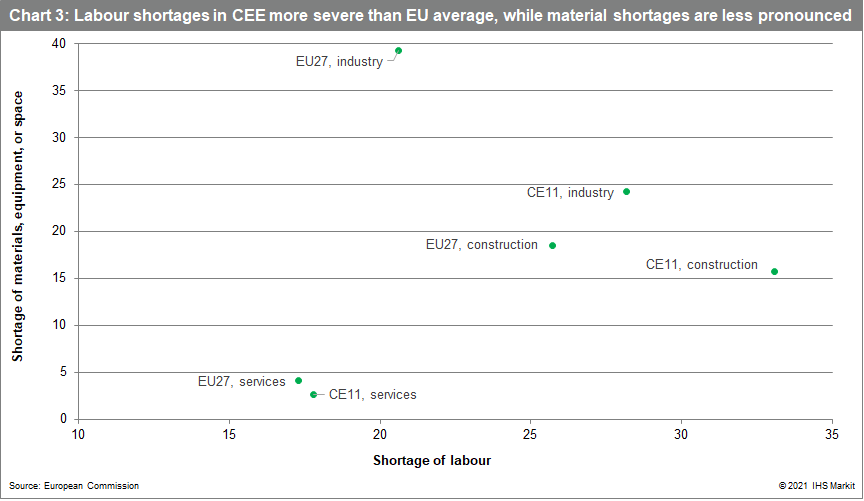

When comparing the average for the 11 EU member states from Central Europe (CE11) versus the European Union as a whole, there are some noticeable differences. Material and equipment shortages tend to be less pronounced in Central Europe, while labour shortages present a bigger problem than in the rest of the EU (see Chart 3). This pattern is similar in the services and construction sectors, and labour shortages are especially pronounced in the latter, putting at risk the planned investments associated with the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). In countries with staff shortages, companies can take steps to try to ease the problem by raising labour productivity through automation and digitalisation, attracting skilled workers from abroad, and/or investing in training and education for younger employees.

Higher producer prices could limit production

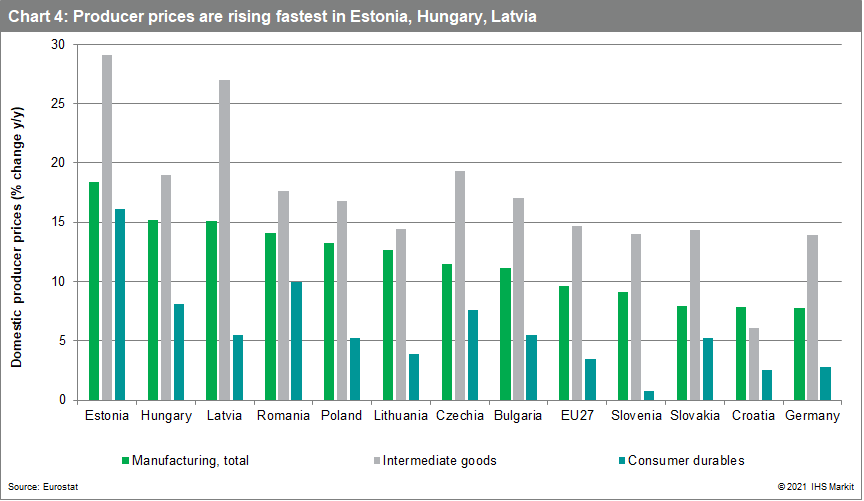

The logistics crunch has contributed to a surge in industrial producer prices across Central Europe, further affected by labour shortages (which are driving up salaries), rising energy costs (impacted by surging natural gas prices), high industrial capacity utilisation levels, and an overstressed transportation system. Manufacturing price pressures have been boosted mainly by intermediate goods, although the prices of consumer durables have also experienced rapid growth in some countries (see Chart 4). By sector, the rise in manufacturing prices has been driven mainly by high price increases for wood and wood products, petroleum, chemicals, rubber and plastics, basic metals, and electrical equipment.

Producer price pressures are expected to remain elevated at least until early 2022, and the decreasing supply and the rising price of natural gas is expected to have a particularly negative impact on energy-intensive manufacturing sectors such as chemicals and basic metals. In a worst-case scenario, the continent could face blackouts that force businesses and factories to shut down.

IHS Markit's supply-side constraint vulnerability index

Given the pressures that companies are facing, IHS Markit analysts have downgraded our short-term GDP growth outlook for Europe in the October forecast round. The third-quarter industrial surveys from Central Europe indicate that the shortages of material and equipment have been highly uneven across sector and country, signaling significant variations in vulnerability, even within a single industry. Nevertheless, a slowdown starting in the fourth quarter of 2021 is now expected across the continent.

In an effort to quantify the impact, IHS Markit has devised a supply-side constraint vulnerability index that ranks CE11 countries in terms of their shortage of material and equipment in significant industries, overall capacity utilisation levels, labour shortages, material shortages in construction sectors, and the strength of growth in producer prices. According to these metrics, Hungary, Slovenia, Estonia, and Czechia appear to be most vulnerable, while Croatia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Latvia are less vulnerable than others (see Chart 5).

When the disruptions will be resolved remains an open question, although variants by industry are likely. The optimistic view is that labour and input shortages will gradually ease as demand in western economies continues to rebound from the COVID-19 virus recession. However, uncertainty remains as to how the stability of global supply chains and the handling of the pandemic will develop, especially in China, Europe, and the United States. Even if the disruptions are resolved quickly, the surge in shipping costs could have a significantly negative effect for small businesses that rely on imported goods, as they tend to have less clout in negotiating fees and space with global shipping lines. Many will struggle to absorb the higher costs, triggering potential layoffs and bankruptcies.

Automation and reshoring provide opportunities

While supply chains have been vulnerable to factory closures and disruptions in transportation, the combination of high shipping costs, long lead times, and rising trade restrictions are triggering a new approach to sourcing decisions. In an effort to reduce reliance on imports from China, EU countries are striving to build a secure and independent supply chain for the key minerals used in electric vehicles (EVs), wind turbines, and aircraft engines.

The EU's 'Fit for 55' plan represents a source of optimism over the medium term, with the potential to encourage faster automation and reshoring of production. The plan aims to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared with 1990 levels, making Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. The programme's initiatives include decarbonising energy production, effectively banning sales of new internal combustion engine cars by 2035, renovating buildings to improve efficiency, and strengthening public transport. The plan is also expected to impose tough conditions on maritime shipping and aviation.

All of these changes will potentially escalate the need for production to be closer to the market, meaning that infrastructure needs to be integrated locally. Increased reshoring is expected over the medium to long term, with European businesses shifting supply chains closer to home, including CEE countries. Indeed, the CEE region's favourable geographical position and lower labour costs compared with Western Europe would play to its advantage, as countries adapt to the pandemic-induced structural changes in supply chains.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsupply-chain-disruptions-in-central-europe.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsupply-chain-disruptions-in-central-europe.html&text=Supply+chain+disruptions+in+Central+Europe+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsupply-chain-disruptions-in-central-europe.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Supply chain disruptions in Central Europe | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsupply-chain-disruptions-in-central-europe.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Supply+chain+disruptions+in+Central+Europe+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fsupply-chain-disruptions-in-central-europe.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}