Rio de Janeiro gang wars

The deployment of the army to combat criminality reflects the marked security deterioration in Rio de Janeiro, compounded by a severe fiscal crisis that has resulted in cuts to the police budget.

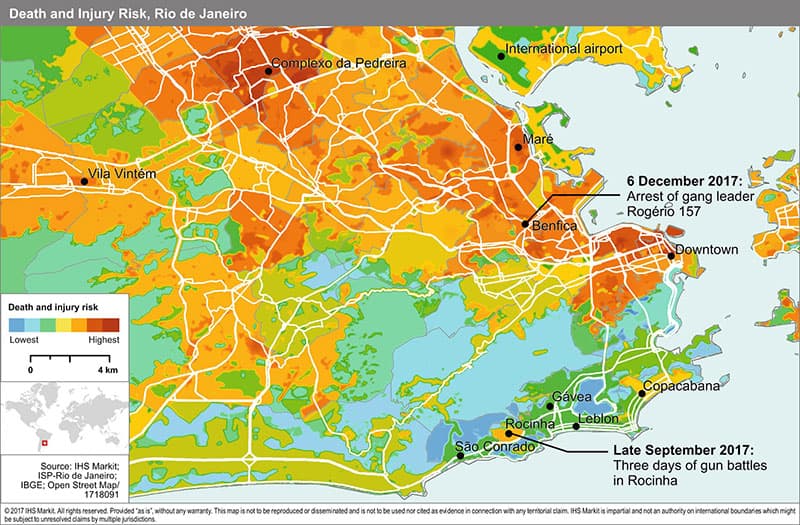

In recent months, Rio de Janeiro has seen a marked increase in intra-gang war and in armed confrontations between police and criminal gangs. Although the incidents have taken place in different slums across the city, of late the main focus of the confrontation has been the slum of Rocinha, in southern Rio. The escalation of violence in Rocinha started in mid-September when Rogério 157, the second in command of the Amigos dos Amigos (ADA) gang fell out with the head of the gang, Antônio Francisco Bonfim Lopes, known as Nem, who is in prison but still controls the ADA. The conflict is over drug distribution and arms trafficking networks, the two main source of income for criminals operating in Rocinha. On 17 September, Nem sent approximately 100 of his foot soldiers to eliminate Rogerio 157 and his followers. This resulted in a series of shooting incidents that lasted several days and caused dozens of deaths - most of them gang members, but two bystanders were also killed. It also disrupted commercial operations and public transportation inside Rocinha and in the neighbouring upmarket districts of São Conrado and Gavea. At the peak of the confrontation, shops in Rocinha closed for several days, while hundreds of schools, including those in São Conrado and Gavea suspended classes for three days. Similarly, the São Conrado metro station was closed for two of days.

In light of the level of violence, and the strategic location of Rocinha, close to the city's main hotel area, the authorities were forced to undertake special security operations, including the deployment on 22 September of a 980-strong battalion. The latter was ordered by the defence minister as Rio is facing a severe fiscal crisis that has seen major cuts in the public security budget and policing. Shortfalls in police strength and capabilities forced the governor of Rio to ask for further support from the federal government, which responded by deploying the National Force, a mobile national police force, in late September.

On 6 December 2017, Rio's police arrested Rogério 157 in the district of Benfica, in northern Rio, 30 kilometres from Rocinha, where he was in hiding following a series of police raids to restore control of the slum and secure his capture.

The Comando Vermelho gang steps in

The 'turf war' for the control of Rocinha has had a city-wide effect, as most of the gang members tasked with hunting down Rogerio 157 came from other Rio slums. According to the police, tapped phone conversations coming from Nem's foot soldiers indicated that many of them came from the slums of San Carlos (Central Rio), Complexo da Pedreira (North), and Vila Vintém (West). More widely, the dispute has expanded into a confrontation between the ADA and the Comando Vermelho (CV) after Rogerio 157 defected from ADA and sought the support of the CV, Rio's main criminal gang, which historically has controlled the upper part of Rocinha. According to the police, the delay in arresting Rogerio 157 was due to the fact that the CV gave him sanctuary in its strongholds elsewhere in Rio.

The defection of Rogerio 157 from the ADA has created a new situation on the ground, of which the main beneficiary has been the CV. According to the police, Rocinha is now under the control of the CV, with Nem's faction having fled or gone to ground while it regroups. Local media are speculating that the ADA is likely to seek an alliance with São Paulo-based Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), Brazil's largest criminal gang, to regain the Rocinha areas that they have lost. The PCC is already fighting a gang war with the CV for the control of drug trafficking across Brazil; it is likely to support the ADA with weapons and money, but not necessarily with manpower.

Outlook and implications

The arrest of Rogerio 157 and the deployment of federal security forces will bring some temporary respite to the security situation in Rocinha and its neighbouring districts, reducing collateral death and injury risk to visitors, as well as business disruption. Although the deployment of additional forces is likely to contain the risk, such deployments indicate a temporary and reactive approach, which is unlikely to lead to a sustained reduction in violent crime. The number of shootings has reduced substantially, but confrontations are likely to break out again, once the military and extra police units are withdrawn. Intervention operations are very expensive in manpower and other resources and the Rio authorities don't have a well-developed security strategy. The initial successes of the Police Pacification Units scheme, initiated in 2008, have been reversed, with police now perceived by the local population as part of the problem. Rocinha and other favela residents see the police as an occupying force, and whatever trust they may have had in them is now lost, mostly due to human right abuses, long documented by local media and non-government organisations. Locals are reluctant to co-operate with the police and justifiably fear that once they leave, the gangs will take back control over Rocinha. The future level of inter-gang violence will largely depend on the strategy the ADA adopts to regain lost ground. An incremental, low-profile strategy could lead to shooting incidents, but would not cause major disruption. Alternatively, the other option would be all-out war against the CV, resulting in severe escalation and repetition of the scale of violent incidents seen in September this year. The latter appears less likely in the next 12 months, as the defence minister has made clear that even if troops are withdrawn, they would be held ready to be return at short notice.

Carlos Caicedo is a Senior Principal Analyst in the IHS Markit Country Risk team

Posted 15 December 2017