Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

May 03, 2021

Protests and terrorism in Chile: Examining the data and what to expect in the coming year

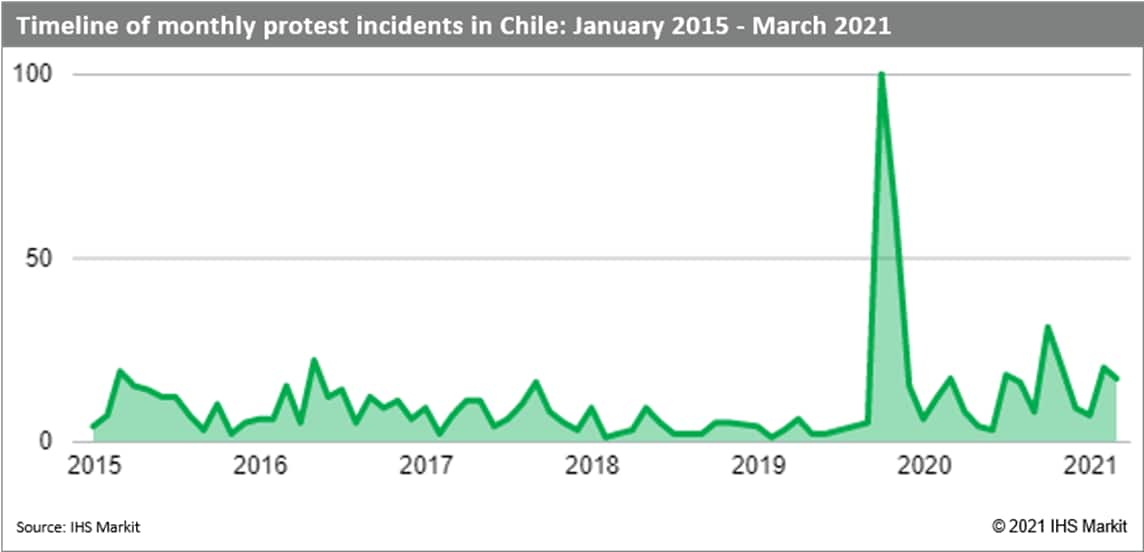

A major wave of civil unrest broke out in Chile in late 2019, leading to the most violent protests seen in the country since the end of the military dictatorship 30 years previously. The following months saw many billions of dollars of property damage and losses from business interruption. While protest levels receded in 2020, partly due to COVID-19 restrictions, elections and a re-write of the Constitution in 2021 will provide further drivers of unrest.

Meanwhile, the campaign of violence over land rights by elements of the Mapuche indigenous group in four southern provinces escalated in 2020. We noted more frequent and comparatively more sophisticated incidents of arson, crude Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs), and shootings. With no sign of a joined-up policy approach to this issue from the government, and with splinter groups emerging and seeking to make their mark, the upward trend in violence is likely to continue.

Analytics using metadata from a large set of security incidents helps to shed light on the contrasting nature of these twin pillars of political violence risk in Chile, and aids analysts to better forecast the future risk environment.

Unrest: Timeline

Protests were triggered in mid-October 2019 by a Metro fare increase in Santiago and quickly escalated to encompass widespread social grievances such as inequality and poor basic services, with demonstrators demanding a change to the country's neoliberal economic model and a new Constitution.

Following around six weeks of uninterrupted and widespread protests nationwide, a pattern emerged from early 2020 of more localized protests at specific hotspots, with short-lived spikes over specific issues such as demands to release arrested demonstrators, pension reform, or against excessive use of force by the police.

Unrest: Hotspots

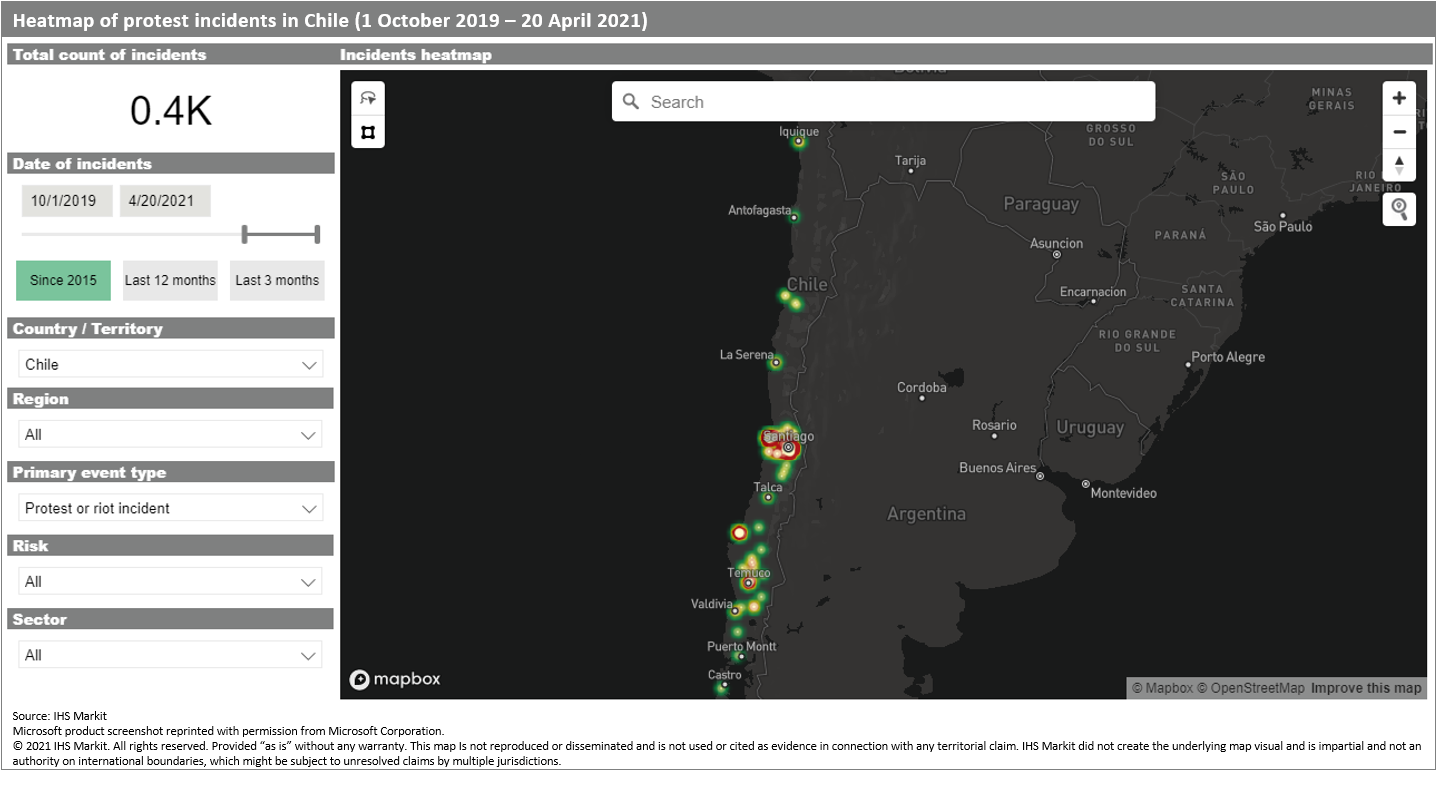

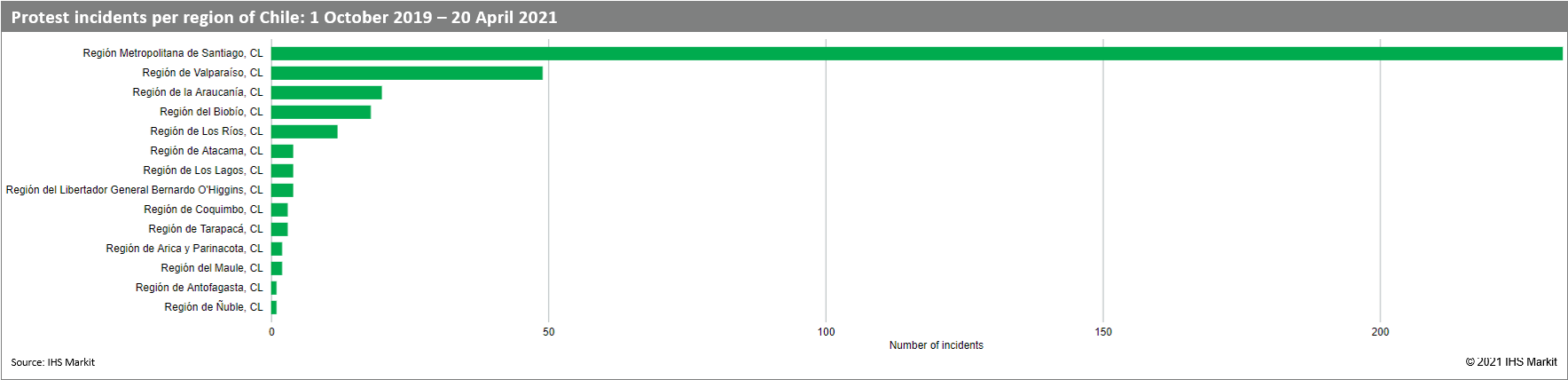

Approximately two-thirds of the protests since October 2019 have taken place in the Santiago Metropolitan Region, in and around the capital city.

Outside the capital, we have tracked around 50 protests in Valparaíso, the eponymously named capital of which is Chile's second-largest city and around 100 kilometres east of Santiago. Next comes a cluster of southern regions, where the abovementioned underlying grievances are also latent but also include demands for the rights of the Mapuche indigenous population.

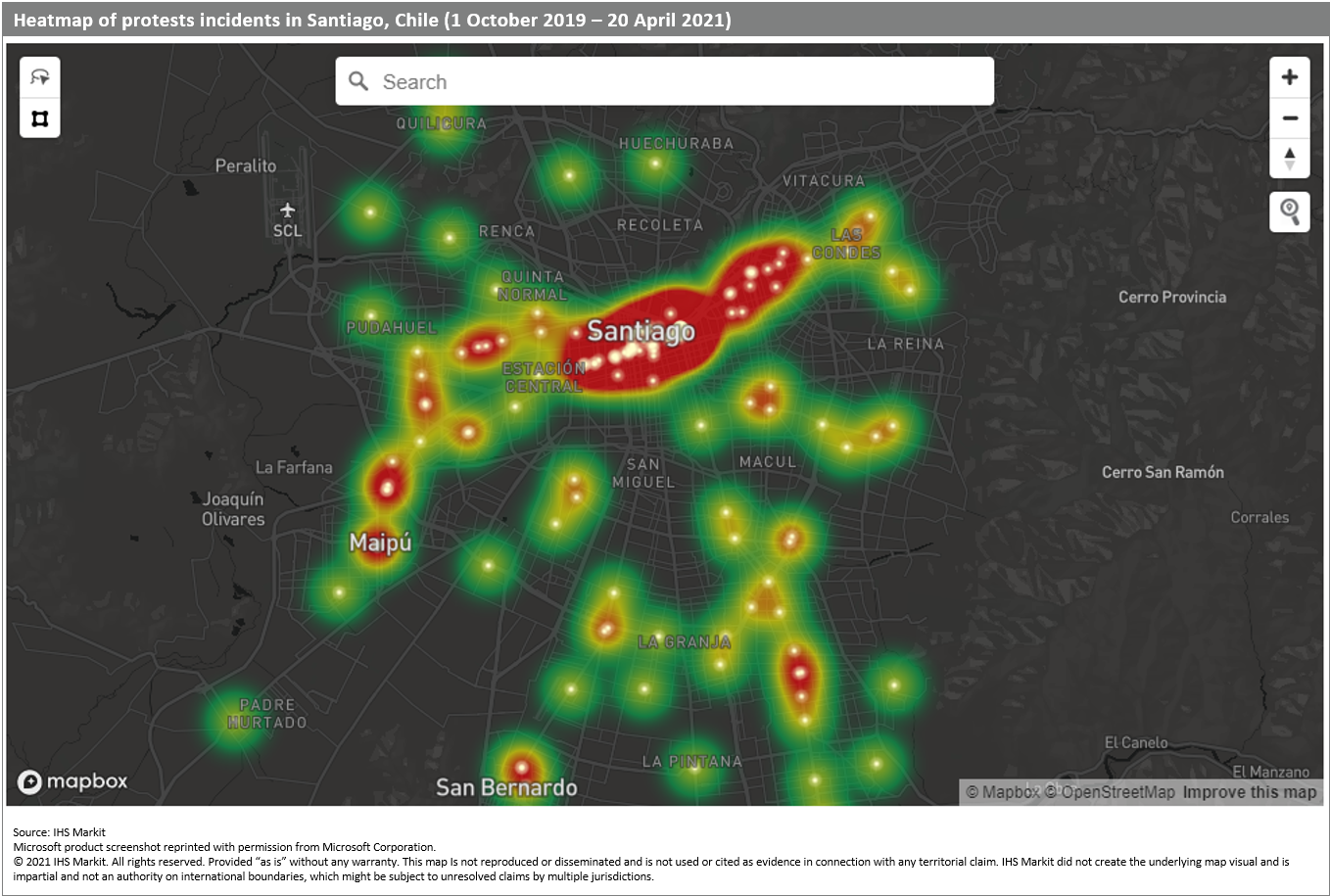

Particular hotspots in and around Santiago include low-income and / or peripheral areas like Maipú, La Granja, La Pintana, San Bernardo, Puente Alto, Pudahuel, Lo Prado, El Bosque, La Granja, and Quilicura.

The principal downtown Santiago protest hotspot is the Libertador Bernardo O'Higgins Avenue - most commonly known as Alameda. A popular gathering spot for demonstrators is the Plaza Italia/Plaza Baquedano at the eastern end of Alameda - seen on the right-hand side of the map below. This area often sees groups of hooded demonstrators confronting the police, erecting burning barricades and throwing sticks, stones and Molotov cocktails, while the police use tear gas and water cannon.

Unrest: Arson and looting

Demonstrators smashed, or set fire to, at least 118 Metro stations, burnt public buses and looted supermarkets, warehouses, pharmacies and shopping centers. Bank branches and cash machines, petrol stations, churches, government offices and police stations across most cities, but especially Santiago, Valparaíso, and Concepción were also targeted. In the six weeks to the end of November 2019, Chile's Construction Chamber of Commerce estimated that protesters caused damage of at least USD4.5 billion. This included USD2.3 billion to public infrastructure (including USD1.94 billion on streets and pavements: USD1.28 billion in Santiago, USD380 million in Valparaíso, USD282 million in Concepción) and USD380 million on the Santiago subway. Additionally, there was a reported USD2.25 billion in damage to non-residential property, such as shops, offices and churches. A separate estimate put losses to the retail sector at USD1.4 billion due to looting and business closures.

Unrest: What's next?

We reduced our protests & riots risk score for Chile several times from early 2020, from the severe band to very high. Initially due to the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on the ability to mount mass protests, then as the government initiated a process to re-draft the constitution - a key protester demand.

Following the "Yes" vote in the October 2020 constitutional referendum, elections are planned for 15-16 May 2021 to choose the 155 members of the constituent assembly charged with the redrafting, which is likely to take at least two years. Nevertheless, 2021 will be politically very hectic amid the COVID-19 vaccine rollout and a new peak of cases, combined with presidential and legislative elections in November. The process of rewriting the Constitution is likely to prompt pressure groups like students, trade unions, and civil society organisations to voice their demands and call for protests if these are not addressed.

In contrast to late 2019, when massive widespread and violent unrest went on almost uninterrupted for weeks at a time, protests through the end of 2021 are likely to be more localized and short-lived. Again, a prime hotspot will be Santiago city center, along the Alameda avenue from Plaza Italia/Plaza Baquedano towards the Central Station and near the La Moneda presidential palace. Outside Santiago, Concepción, Valparaíso, and Antofagasta are also likely to be impacted. Retail stores will remain the primary target of looting, while public transport infrastructure, police stations and vehicles, and government buildings are likely targets of arson.

While our baseline scenario is that a repeat of the levels of violence of late 2019 is unlikely, we are monitoring indicators of a potential escalation, including:

- COVID-19 cases continue to increase despite the vaccine rollout, forcing the government to extend strict lockdown measures and postpone the elections indefinitely. Despite a worsening public health situation, COVID-19 assistance programmes are removed.

- Security forces are seen as using excessive use of force, either when controlling protests or when enforcing lockdown measures.

- The ruling center-right coalition Chile Vamos (Chile Let's Go) and its allies obtain more than 30% of the seats on the Constituent Assembly, thus being able to block major policy changes.

Southern terrorism: Trends and hotspots

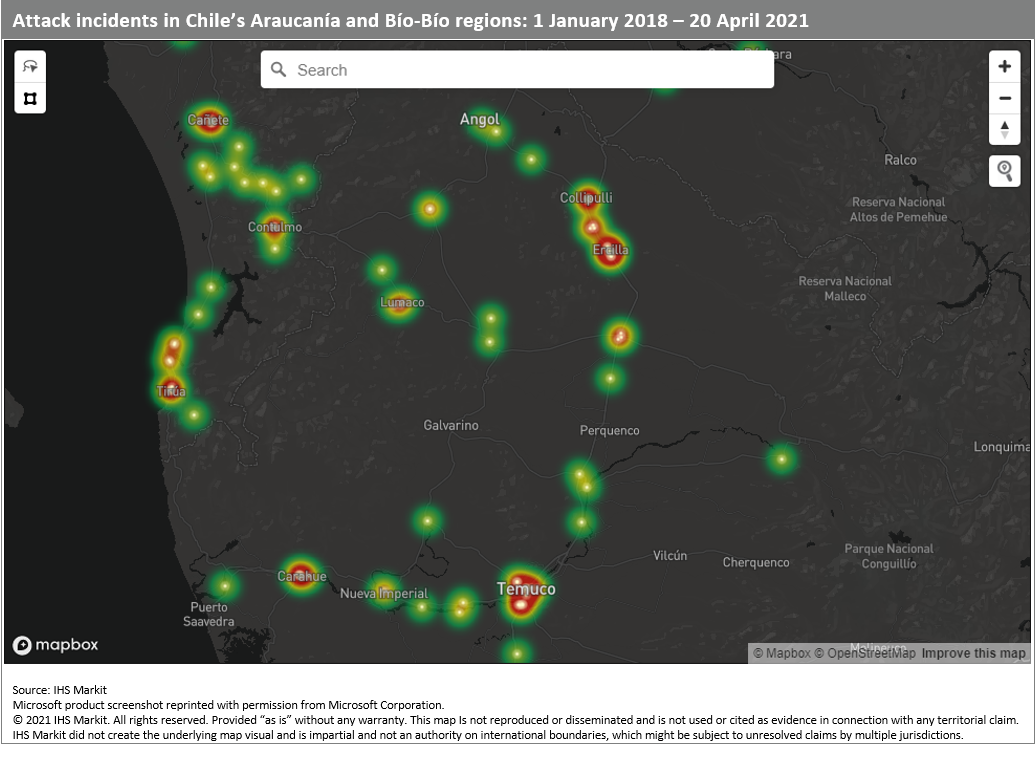

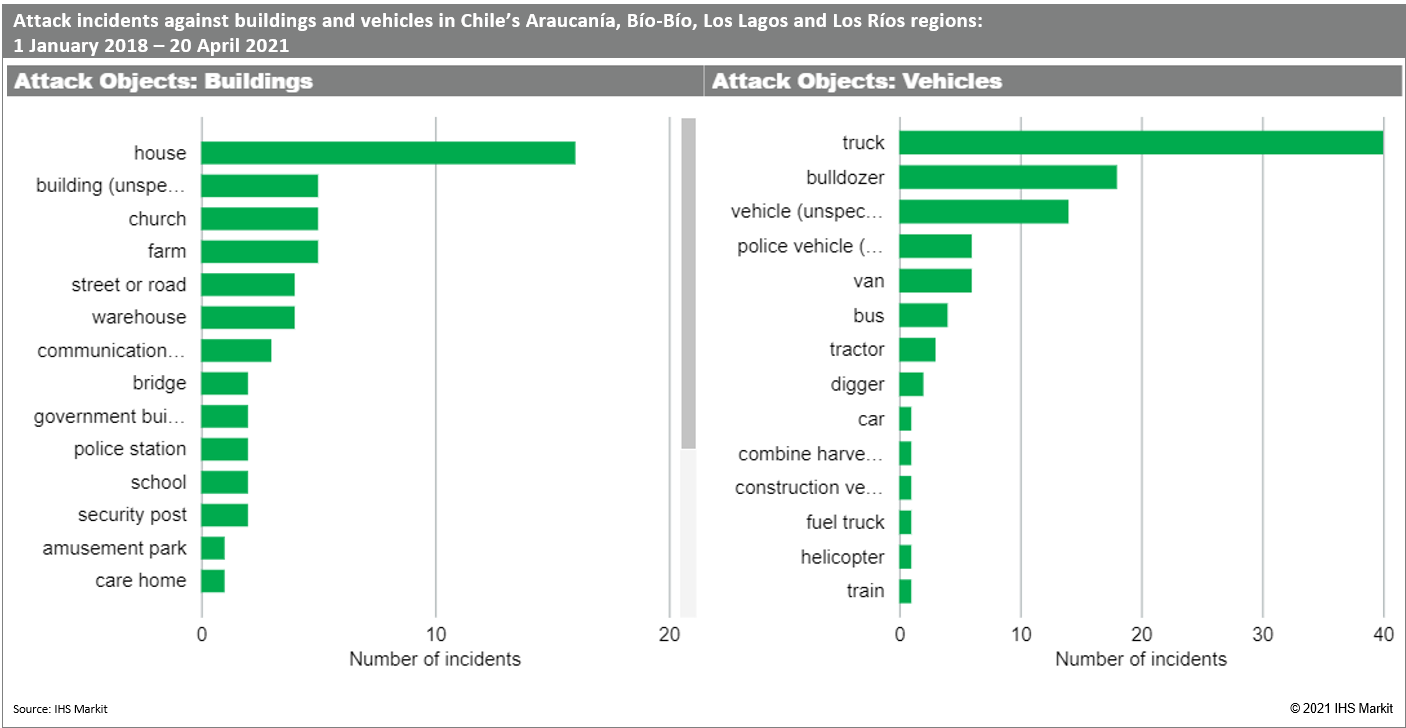

There is a high risk of arson attacks by Mapuche indigenous extremists against private assets in the Araucanía and Bío-Bío regions and, to a lesser extent, in Los Lagos and Los Ríos. This southern zone has a long-lasting conflict over land restitution, with extremist groups becoming more organised and sophisticated.

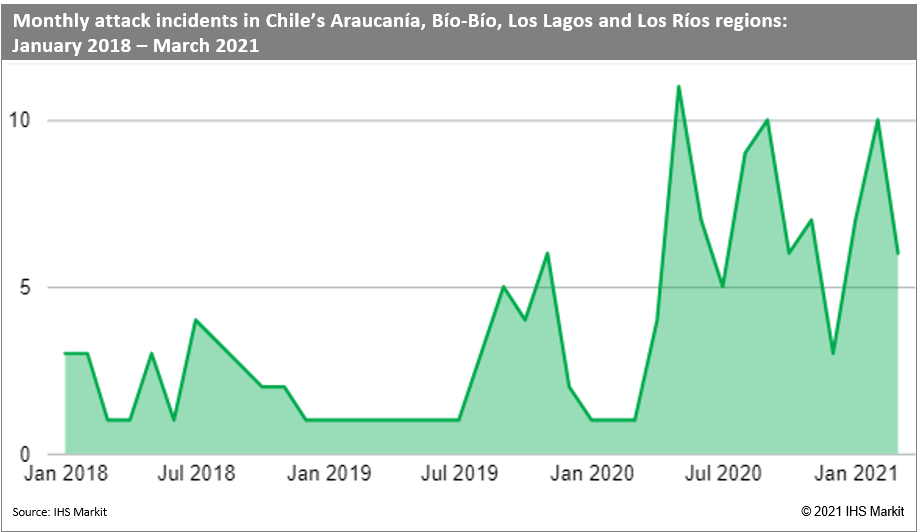

The number of attacks has increased since early 2020, despite lockdown restrictions implemented during the pandemic.

Southern terrorism: Hotspots

The Araucanía region has traditionally been the main hotspot for rural violence - particularly Collipulli, Ercilla, Freire and Victoria. In recent years, however, we have seen an increase in incidents in Bío-Bío (from 1-2 per month between January 2018 to April 2020 to often having between 4 and 7 since) and, to a lesser extent, the Los Lagos and Los Ríos regions. The province of Arauco within Bío-Bío, which borders Araucanía region, has become a key hotspot over the past year, particularly in Cañete, Contulmo and Tirúa.

Southern terrorism: Modus operandi and target sets

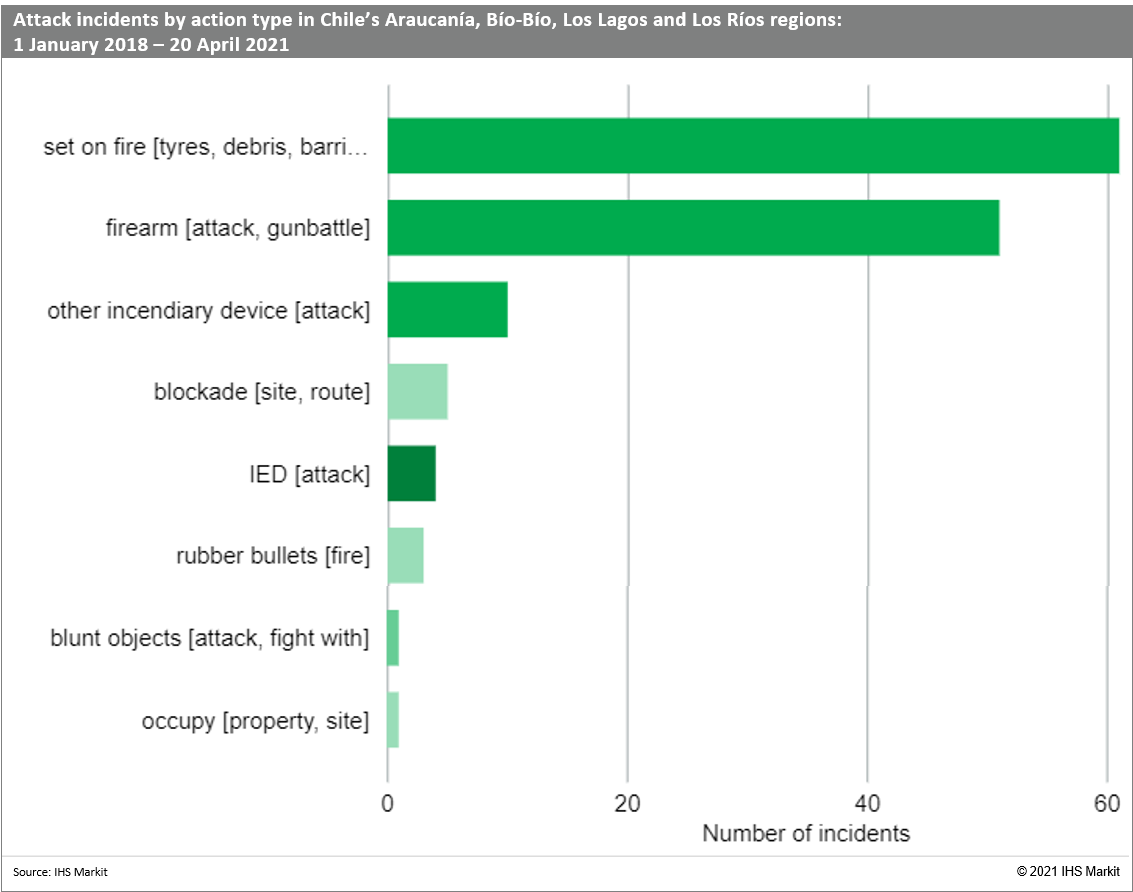

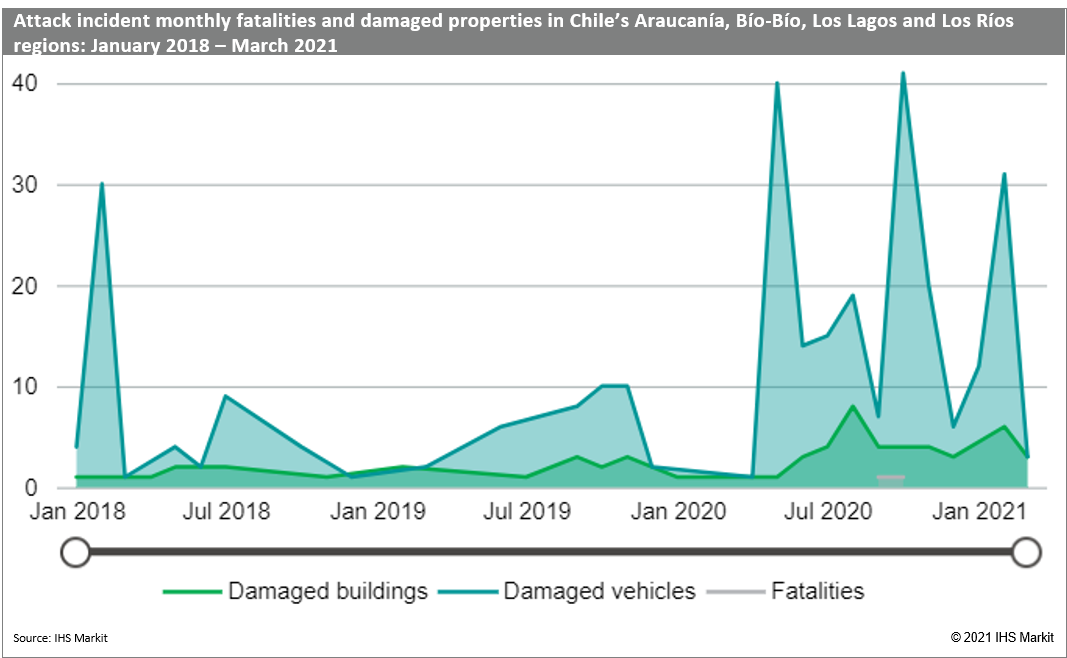

The main targets have historically been vehicles, machinery and warehouses from forestry and agribusiness - the sectors developing the most prominent resources in this area. These tend to be targeted using arson or crude IEDs.

More recently, the target set has expanded to include a broader set of assets such as telecoms towers, schools, churches and tourism assets like holiday cabins. There have also been several attacks on helicopters and light aircraft servicing forestry or agribusiness companies, involved in extinguishing forest fires or belonging to the police. Most have been when they were parked on the ground but there have also been a small number of reports of shots being fired while airborne.

The targeting of vehicles (particularly cargo trucks) has increased notably since May 2020.

A common tactic is stopping cargo trucks at impromptu checkpoints, forcing the drivers at gunpoint to leave before setting fire to the vehicles. Firearms attacks on the roads are also increasingly common, targeting police vehicles or cargo trucks. Specific hotspots for attacks against trucks are Route 5 (a tranche of the Panamerican Highway), particularly between Collipulli and Victoria, and the P-60 and P-72, linking Cañete, Contulmo and Tirúa.

The graph above shows fatalities are relatively rare. For example, incidents in September and October 2020 of a police officer killed in an ambush on his part car on Route 5 in Araucanía, and a passenger in a car shot at after apparently happening to inadvertently surprise extremists fleeing from an arson attack in Bíobío. However, shooting attacks on roads do also pose collateral injury risks, with a small number of cases so far of passengers of nearby vehicles being hit by stray bullets.

Southern terrorism: What's next?

The abovementioned risks are likely to remain high in the coming year, as radical groups are becoming more organised (e.g. the carrying of firearms and use camouflage clothing and bulletproof vests are now much more common) and their attacks more aggressive, often burning several vehicles or machines, sometimes more than ten, at a time. For example, on 5 April 2021, eight masked individuals broke into an estate belonging to forestry firm Mininco in Toltén, Araucanía, and set fire to eight vehicles, including a cargo truck, a forestry crane and harvesting machinery.

Furthermore, the emergence of splinter groups is leading to turf disputes which can be a further driver of violent risks, with some groups likely to mount high-profile attacks in order make a name for themselves and assert their capabilities. Apart from the traditional Coordinadora Arauco Malleco (CAM) and its splinter group Weichán Auka Mapu (WAM), other groups have also become more prominent over the past years. For example, Resistencia Mapuche Lafkenche claimed a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) detonation near the Lleu Lleu bridge, Arauco province in April 2020, which caused no casualties or damage. Chilean intelligence services believe some of these groups are involved in criminal activity, such as drug trafficking and the illegal timber trade, in collaboration with organised crime groups operating out of Temucuicui.

President Sebastián Piñera lacks a comprehensive security strategy in the area after withdrawing a specialised task force following the killing by the police of a Mapuche community member in November 2018, amid accusations of excessive use of force. The government's strategy for the rest of 2021 will probably center around an increased deployment of security forces, but this is likely to simply displace hotspots temporarily rather than address the underlying drivers of violence. The government's security agenda, which includes changes to the anti-terrorism law such as toughening penalties and allowing undercover agents in counter-terrorism operations, has been delayed in Congress due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Even if some of the bills are approved, it would take time for them to yield results. Furthermore, any significant progress with these legal amendments would probably be marked by immediate retaliatory attacks. The lack of consensus among the political parties on the most effective approach to deal with the issue, with some parties arguing it is a political issue and others that it is purely a security matter, will continue to hinder any progress towards reducing violence. The new Constitution is likely to include the official recognition of indigenous peoples. While this would be well received by many mainstream Mapuche communities, it is possible that certain extremist groups would see this as vindication of their armed struggle and thus intensify their demands and associated armed campaigns for land restitution.

This is the fourth in a series of blog posts leveraging insights gleaned from security incident metadata in dashboards from our Foresight platform, following those on Egypt, the Philippines and Mozambique

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fprotests-and-terrorism-in-chile-examining-data-forecast.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fprotests-and-terrorism-in-chile-examining-data-forecast.html&text=Protests+and+terrorism+in+Chile%3a+Examining+the+data+and+what+to+expect+in+the+coming+year+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fprotests-and-terrorism-in-chile-examining-data-forecast.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Protests and terrorism in Chile: Examining the data and what to expect in the coming year | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fprotests-and-terrorism-in-chile-examining-data-forecast.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Protests+and+terrorism+in+Chile%3a+Examining+the+data+and+what+to+expect+in+the+coming+year+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fprotests-and-terrorism-in-chile-examining-data-forecast.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}