Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Dec 08, 2021

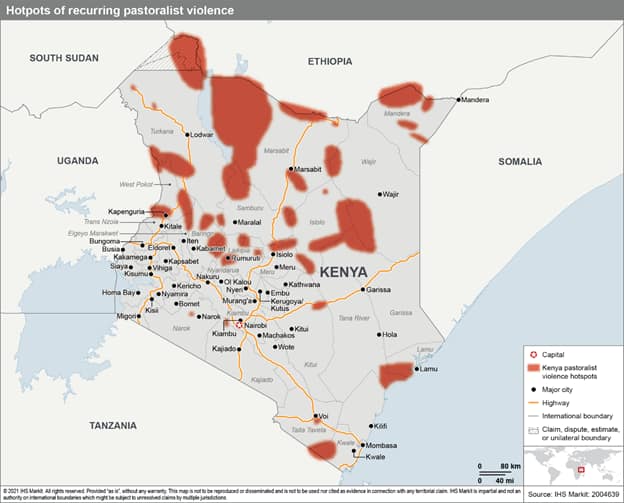

Pastoralist violence in Kenya

Violence involving Kenya's pastoralists over access to pasture has coincided with a drought that Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta deemed a "national emergency" in September. Over the course of 2020 and 2021, IHS Markit has recorded a rise in small arms attacks against security forces and smallholder farmers in Laikipia county, a hotspot for violence over land rights involving nomadic pastoralist groups. Earth scientists predict more frequent droughts in East Africa in the coming years, which would increase the likelihood of violent competition for pasture. Land claims by rival groups seeking to improve their access to government funds and development or improve their chances of election to public office are also drivers of violence, with the risk of land-based violence increasing in the lead-up to the August 2022 general election.

Resource scarcity caused by increasingly frequent drought is likely to drive violent competition for pasture and water.

Traditionally, during periods of low rainfall, affected herding communities flock to spillover pasture areas, which often are either oases in otherwise arid areas or privately owned land nearer to Kenya's densely populated and fertile high-rainfall areas. Arrivals from drought-affected areas often come into conflict with others to gain access to pasture, with a high tendency for violence involving the use of intimidation, cattle rustling, fighting with firearms, including assault rifles, and property destruction. According to a report by Chris Funk, director of the Climate Hazards Center at the University of California, Santa Barbara (United States), poor 'long rains' - the longer of East Africa's two rainy seasons - have been much more common (once every two or three years on average) since the year 2000, compared with prior data recording drought around every five years in the 20th century. If these conditions persist, food insecurity and violent competition for pasture are likely to rise consistently.

Rising human and livestock populations are likely to exacerbate land-based conflict.

Between 1989 and 2019, the human population of Kenya more than doubled, and between 1999 and 2009, the rate of population growth in Kenya's Arid and Semi-Arid Lands (ASAL) was almost double that in high-rainfall areas. Livestock numbers have also increased greatly. This trend is unlikely to stop; the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) forecasts that cattle production in Kenya is likely to increase by 95% between 2015 and 2050.

Yet pastoralist violence also occurs when resources are abundant, highlighting that poor access to pasture is a critical determinant of conflict.

Private land ownership, often on a very large scale, in certain areas of Kenya's ASAL reduces nomadic pastoralists' access to pasture; landowning communities perceived to be unfairly benefiting from land resources are often the targets of violence. For example, wildlife tourism lodges on privately owned land in Laikipia were shot at in 2017 by nomadic pastoralists who also carried out systematic illegal incursions with grazing animals, although no tourists were injured. Public institutions have also registered large tracts of land claimed by local communities for the development of transport and military infrastructure projects.

Rival claims over land earmarked for infrastructural development continue to motivate disputes and, at times, result in armed violence.

The ongoing development of the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor project - a transport network and 50-kilometer-wide special economic zone to envelop it - has brought about many such claims. Increasing infrastructure development across northern Kenya is likely to drive this risk in the coming years. Expecting a windfall for local government and communities, the Meru county government claimed jurisdiction of Isiolo county's Ngaremara ward, inter-communal fighting over which resulted in the deaths of 17 people between 2017 and 2018. Previously, in 2014, expecting a highway to be built between Marsabit town and Moyale town, new settlers occupied areas along the proposed route, including Funan Nyatta, Bori, and Bosnia Junction. These areas became conflict hotspots, with members of rival ethnic groups attacking settlers with small arms in attempts to drive them away and replace them.

The August 2022 election season risks serving as motivation for pastoralist conflict in Kenya's ASAL, especially if coinciding with further drought.

In past election years, land invasions have been encouraged by some candidates to force away a rival's voters. These have included the use of lethal violence and theft of livestock, replacing landowners with a candidate's supporters. In Laikipia North, for example, the number of registered voters grew from 27,903 in 2013 to 46,942 in 2017 following systematic incursions onto private land in the area by nomadic pastoralists who reportedly displaced thousands of people. The violence was allegedly encouraged by statements of political figures who claimed their voters deserved grazing rights on privately-owned land.

Indicators of changing risk environment

Increasing risk

- Below-average rainfall between March and May 2022 in Kenya's ASAL, prolonging drought conditions would increase the competition for pasture turning violent.

- Political candidates claiming pastoralist groups' rights over privately owned land (most likely in Laikipia county) to win voter support in the August 2022 election would increase the likelihood of violent incursions into contested areas.

Decreasing risk

- Security forces deploying pre-emptively to regions where political candidates are likely to foment attempts to violently disperse supporters of rival candidates from their constituencies ahead of the August 2022 general election would mitigate the risk of violent land incursions.

- Improved implementation of the Community Land Act 2016 would increase nomadic pastoralist communities' access to land registry services and decrease the likelihood of grievances over government appropriation.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpastoralist-violence-in-kenya.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpastoralist-violence-in-kenya.html&text=Pastoralist+violence+in+Kenya+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpastoralist-violence-in-kenya.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Pastoralist violence in Kenya | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpastoralist-violence-in-kenya.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Pastoralist+violence+in+Kenya+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fpastoralist-violence-in-kenya.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}