Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Nov 05, 2020

As Illicit Shipping Becomes More Prevalent, How Banks Can Best Respond

This article originally appeared in Documentary Credit World, October 2020

The maritime sanction compliance advisories published by the United Nations Security Council Panel of Experts for North Korea, the US Department of Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) in May 2020 and the UKs Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI) in July 2020, have all added to the growing burden on vessel screening by financial institutions.

In light of these advisories, it would seem opportune to identify how big the actual burden is, where the pain-points exist, and how they could be managed.

Four advisories published by OFAC since February 2018 have all concentrated in detail on a few distinct areas as the basis for a sanctions screening program concerning vessels and their movements and owners. *These two elements are the IMO (International Maritime Organisation) number and AIS (Automatic Identification System) movement tracking devices. The reason for the emphasis on these two data elements is that they are the cornerstones of vessel identification and tracking; without them it is impossible to formulate sanctions policy from the regulators' perspective and to manage it day-to-day from a banking implementation point of view.

In this manner, the OFAC and OFSI Advisories recommend compliance mechanisms that go well beyond the standard screening of owners, operators and vessels against sanctions lists. The new compliance measures include historical and continued analysis of AIS transmission data, AIS-related contract clauses, careful scrutiny of shipping documents, and 'know your vessel' checks.

In regard to the IMO number, the OFAC advisory highlights the need for thorough research into a vessel's IMO so that a historical picture can be identified as to activity, route, flag, safety record, and age. Such information provides a behavioural picture of a vessel's propensity to evade sanctions despite not currently being designated.

The expected risk indicators and red flags now include the following:

- AIS transmission requirements and best practice to be shared with customers and partners

- AIS transmission gaps to be identified for risk in certain 'hotspots'

- AIS history and monitoring

- Vessel due diligence

- Ship-to-Ship checks for certain cargo types in high-risk geographies

- Shipping document review

- Clear communication of sanctions requirements to partners

- Know Your Customer due diligence

Significant emphasis is placed on AIS in the OFAC advisory as an antidote to the dark status of a ship. Dark status is the term used when the AIS device is switched off and the ship is no longer fully visible, it is very often an enabler preceding a vessel evading sanctions. OFAC clearly views the monitoring of AIS for dark activity as an indispensable part of a maritime sanctions screening program but, as compliance teams are fully aware, these new measures have cast a very wide net in terms of the number of vessels now covered as potentially sanctionable and high-risk.

Using maritime data to identify what is now captured in the OFAC net we can uncover the scope of potential sanctionable activity for banks and others to be aware of.

There are nearly 700 sanctioned vessels on various watchlists today and these lists are easily maintainable from a trade operations screening perspective. In addition, there are vessels that are known to have made sanctioned port calls or fly a flag from a designated country such as North Korea (DPRK) or Iran which places them in a sanctioned or higher-risk category. To provide an example of the numbers in this classification, in the last three months (July-October 2020), the number of tankers, bulkers, general cargo and container ships to have visited sanctioned ports are:

- 2,281 vessel arrivals at Iranian ports, of which 402 are unique vessels

- 60 vessels arrived at DPRK ports, of which only 20 are unique vessels

- 1,353 arrivals to Venezuela, of which 193 are unique vessels**

The figures here in regard to sanctioned vessels and sanctioned port calls comprise a very small percentage of the overall merchant shipping fleet. It also points to a shift in how sanctions are evaded by vessels and entities behind them; as the number of calls to sanctioned ports is low, how are cargoes being shipped and loaded? Today, they are mostly being transferred from vessel to vessel under the darkness of AIS disablement or through the spoofing of MMSI (Maritime Mobile Service Identify, a nine-digit code broadcast over radio channels) and satellite signals. In this context, the monitoring of designated and sanction watchlists is not enough to effectively detect illicit maritime behaviour anymore, hence the shift to suspicious activity based on AIS.

Conversely when we look at the number of vessels now captured through the OFAC advisory requirements which concentrate heavily on potential risk typologies attributed to ships, the numbers rise significantly.

In the same July-October 2020 period, instances of dark activity totaled 3,795 separate occasions where a sanctioned port call or suspicious ship-to-ship transfer (STS) could have occurred. Overall, the number of vessels that are not currently sanctioned by OFAC but have engaged in 'dark activity' in the last 12 months and may, potentially, have led to a sanctioned port call or STS in a high-risk location is 8,324 unique vessels. In this context, dark activity means a gap in AIS transmission within a known hotspot as defined by OFAC such as the South China Sea, Gulf of Tonkin, Yellow Sea, Persian Gulf, etc. Among these 8,324 unique vessels, only 339 actually made a visible, with AIS switched on, sanctioned port call in the last 12 months.

Whilst not all vessels in this 8,324 list of suspicious types are evading sanctions, it does highlight the number of vessels that OFAC has now effectively placed into a 'warning' zone, separate from its original blocked list.

To illustrate the point of how a vessel can be non-sanctioned but participating in dubious practices, we can take a working example from this pot of 'warning' vessels. A crude oil tanker, running a Panamanian flag, with a registered owner in the Middle East and a clean bill of health in regard to OFAC vessel and owner sanction status looks initially innocuous. But a closer inspection highlights why, with the new OFAC shipping advisory lens passed over the vessel, it becomes potentially suspicious:

- The ship has had only four known port calls in the last 12 months

- She has made only two ship-to-ship cargo transfers in the last 12 months

- The vessel's AIS was switched off for 192 days in the last 12 months

The port calls and STS activity for this vessel are below average for a similar oil tanker and would rank it as fairly inactive. This information is further compounded when analysing the vessel's entire movement history over the previous 12 months.

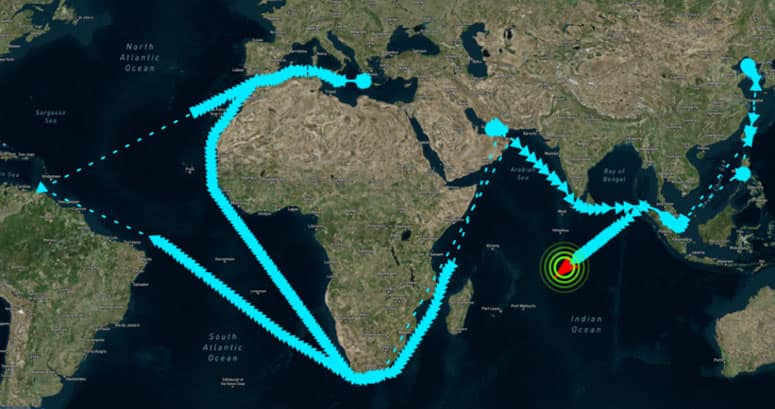

Figure 1: Potentially suspicious, oil tanker movement history

In the graphic, the dotted lines are AIS transmission outage periods. They all occur in three major hotspots recognised by OFAC in their advisory documents: anchorage areas of Venezuela; the South China Sea; and the Persian Gulf.

Furthermore, the vessel's draught, a measurement that can determine the mass of cargo onboard the ship, highlights a change when it moved across the Atlantic Ocean towards the Mediterranean Sea. The change to the draught suggests it was loaded with crude oil at Venezuela but the subsequent voyage after this probable port call led to a vessel with nowhere to off-load as the ship's destination noted 'For Orders'. ***In the oil industry, a vessel on the water with no current buyer is viewed as distressed and is not a healthy sign. The remainder of the voyage shows the ship heading towards Greece, making a full turn, sailing south along western Africa, around the Cape of Good Hope, and back north towards the Persian Gulf before heading to Asia and discharging its cargo in Dalian, China, in Oct 2020, nearly six months since loading the cargo in mid-April.

Obviously there are numerous risks here. Oil cargo from Venezuela to China, the proximity of Dalian to the North Korean border, significant gaps in the AIS signal, loitering in the Mediterranean Sea and Persian Gulf, a non-specific route, and a valuable cargo with no predefined customer. In conjunction with the evident risks, this example also illustrates the difficulties of managing ship movements for sanctions screening purposes.

The extraction of data to analyse this particular journey, the vessel particulars and other relevant details is a time-consuming process and requires objective analysis to determine whether the outcome of this vessel conforms to a bank's risk appetite or not. Whilst this example would highlight a vessel that might not pass a compliance check, there are others that will pass the check but still require the same level of research and investigation. However, OFAC's seemingly straightforward instruction in its shipping advisories that "[AIS] data should be incorporated into due diligence practices," will present significant practical challenges. The detection of genuinely suspicious AIS transmission outages poses considerable questions on data input, data quality, false positives and, most obviously, time and resources.

So how can operations teams be effective and avoid being swamped with multiple instances of false positives when managing maritime sanctions?

AIS outage gaps can have various legitimate explanations: poor line of sight in inland waterways can cause transmission issues; high traffic density areas; severe weather conditions; or even vessels discharging liquified natural gas which can cause sparking may have the broadcast signal switched off. Therefore, an AIS-related compliance monitoring programme that does justice to the complexity of the data requires an accredited content management system which allows for decision making in real-time. Without such a system, vessel due diligence checks, similar to that performed on the above-mentioned ship, can take up to an hour or more.

Applications that understand the anomalies within AIS data are commercially available and they include inputs based on the information already discussed but the key to managing the new OFAC advisory is understanding which vessels pose potential compliance issues. Quantifying this and thus providing a semblance of security similar to the black and white, yes or no, certainty of a watchlist is paramount. The quantification in the examples used here has been done and roughly equates to the 8,000+ vessels identified earlier as potentially falling within a 'warning' indicator range.

So, what is the overarching criteria and how can confidence levels be raised when handling these warning vessels? Factors to consider include:

- Ensure your maritime sanctions screening provider understands the concept of a 'warning' classification for vessels based on AIS activity, STS cargo transfers, and flag changes. This 'warning' classification, if managed and maintained by your solution provider, removes a considerable segment of heavy data analysis from the bank operations side and conforms to OFAC recommendations

- Only certain types of goods and vessels will engage in ship to ship transfer; most notably tankers and bulkers. This reduces the number of vessels that can come under investigation for this activity type

- AIS outages should be handled operationally on a time-length basis. Short transmission outages can be justified as being of lower risk due to the time it takes to make a port call or to transfer cargo between ships

- Vessels engaged in suspicious activity have a general pattern of doing so, often activating many different red flags in the process. Such vessels do not have a history of single instance red flag lapses

Taken together these steps, with the right application and use of technology, can make the overall process of screening for maritime sanctions easier and less burdensome.

To conclude, the extra workload on bank trade finance operations teams regarding maritime screening has come about due to expansion of international sanctions evasion tactics by shipping companies, corporates, and nation-states who are finding new ways of circumventing regulations. The old methods of discharging or loading cargo in sanctioned ports, continuing to use sanctioned vessels and flags of convenience are not as practicable today as they used to be for North Korea and others. Instead we see STS transfers, dark vessels, and signal spoofing as the new tools in the armour of those bypassing shipping sanctions. This has meant that new measures proposed by regulators have become increasingly complex to implement for banks on the receiving end. Even so, there are ways to solve them and in many cases as effectively as watchlist management processes, but it does require the right level of technology. Shipping algorithms with artificial intelligence and machine learning properties can be utilised in a manner similar to KYC screening applications that cover individuals, entities, and corporates. Artificial intelligence methodologies applied to a maritime sanctions workflow can at the very least understand who the high-risk and 'warning' vessels are and act on them appropriately. This provides operational compliance teams with the best opportunity for getting back to the certainty of a watchlist approach.

https://ihsmarkit.com/Info/0720/risk-and-compliance-newsletter.html

*The OFAC advisories include: "Sanctions Risks Related to North Korea's Shipping Practices" (23 Feb 2018); "Sanctions Risks Related to Petroleum Shipments involving Iran and Syria" (25 Mar 2019); "Publication of New and Amended Iran-Related Frequently Asked Questions" (5 Sept 2019); and "Guidance to Address Illicit Shipping and Sanctions Evasion Practices" (14 May 2020).

**Sourced from IHS Markit, Trade Compliance Secure. Data taken from the period of July 15th-October 15th, 2020

***'For Orders' is a term entered by the ship's captain to the vessel's 'Destination' field and implies that the ship has no current destination and is available for charter. For Order was the entry used in the destination field for the oil tanker, Grace 1 (also known as the Adrian Dariya), owned by Iran and seized by the UK Royal Navy in the Mediterranean Sea in July 2019.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fillicit-shipping-becomes-more-prevalent-how-banks-can-respond.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fillicit-shipping-becomes-more-prevalent-how-banks-can-respond.html&text=As+Illicit+Shipping+Becomes+More+Prevalent%2c+How+Banks+Can+Best+Respond+++%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fillicit-shipping-becomes-more-prevalent-how-banks-can-respond.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=As Illicit Shipping Becomes More Prevalent, How Banks Can Best Respond | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fillicit-shipping-becomes-more-prevalent-how-banks-can-respond.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=As+Illicit+Shipping+Becomes+More+Prevalent%2c+How+Banks+Can+Best+Respond+++%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fillicit-shipping-becomes-more-prevalent-how-banks-can-respond.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}