Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Sep 14, 2021

How permanent will the post-covid decrease in births in Europe be?

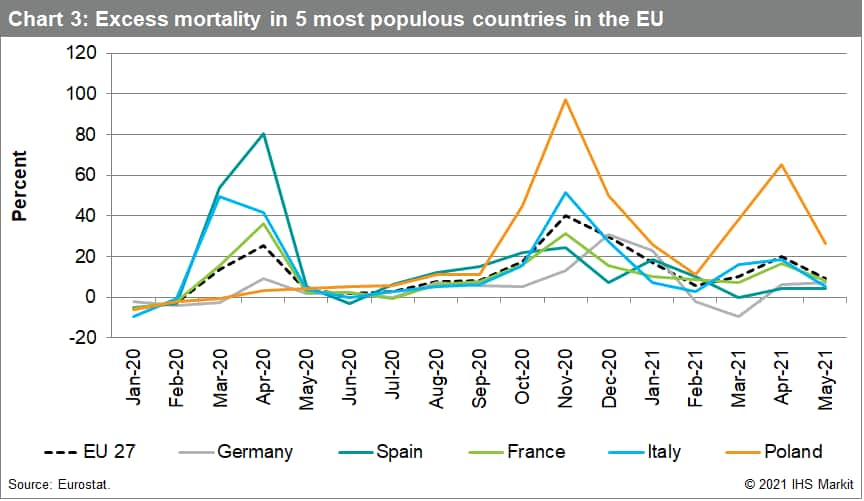

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) virus spread in Europe overwhelmed even the strongest health systems and resulted in peaking excess deaths (the percentage of additional deaths compared to the average number of deaths in the same month of the period 2016-2019) in April and again starting November last year. The COVID-19 outbreak increased economic uncertainty and health risks, but also disrupted marriage markets. Moreover, experience from the last pandemics and other high mortality events suggests that a peak in deaths is followed by a dip in births with approximately nine months lag.

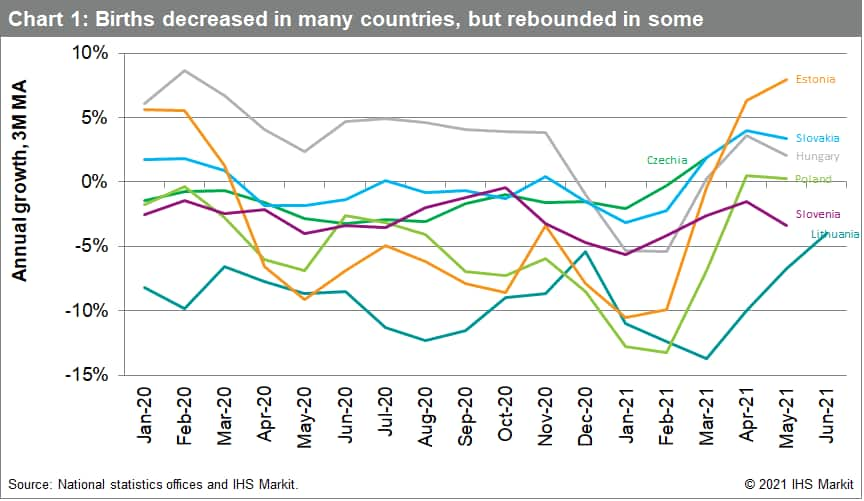

Indeed dynamics of births deteriorate in most European countries (for which data is available) at the beginning of 2021 in the aftermath of quarantine, which was introduced in March 2020 and first peak in excess death a month later. Later some rebound in births has been recorded as well, however, the situation differed among countries.

Italy and Spain recorded rather high excess mortality during the first wave of the virus, and both countries have witnessed an acceleration in the decline in births in the first quarter of 2021. The trough in births was reached about 8-11 months after the peak in excess deaths. In Poland, excess mortality in April 2020 was not peaking, but the number of births contracted strongly in January 2021. That suggests that the fear of virus and news from other countries could have played a role despite the fact that COVID-19 was still having less material impact at home at a time.

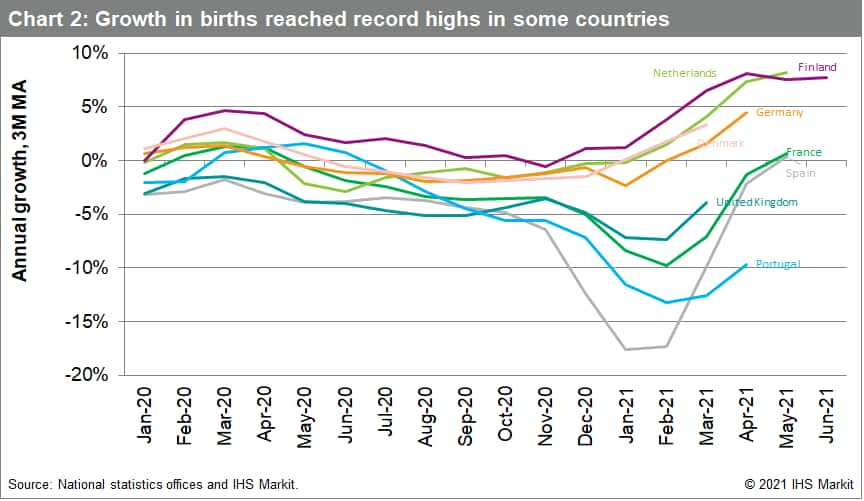

However, some countries have fared better than others. The annual growth in the number of births in the Netherlands during the last three months reached 8.2% in May and was the highest since 1998. In Finland growth reached close to 8% in June - a historical high. In Germany, Slovakia and Denmark growth was the highest since 2017.

Our analysis shows that further dips in birth in the near future are likely. The number of births in Poland is likely to be hit once more towards the second half of 2021 and the beginning of 2022. Repeated dips in births could be again expected in the five most populous countries in the EU as well. Excess mortality was higher in Germany during the second wave and just as high as during the first wave in Italy. Excess deaths remained considerably high in France as well.

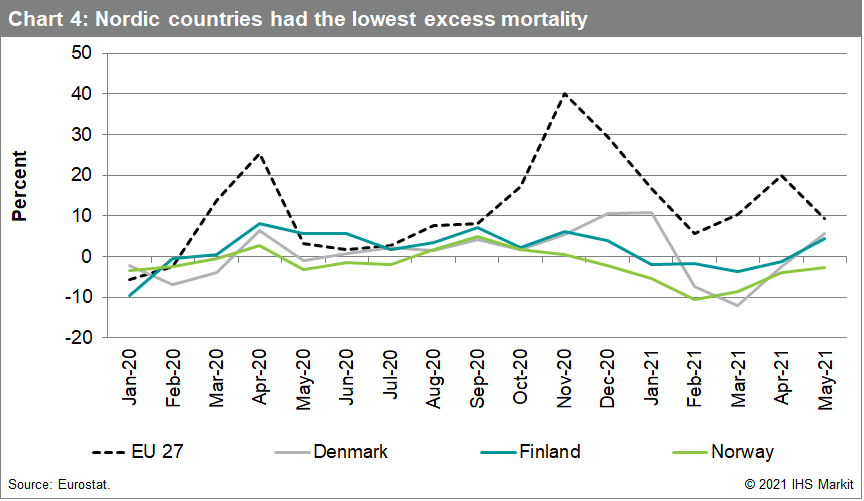

At the other end of the spectrum, Nordic countries (with the exception of Sweden which has resisted the strict lockdown) have experienced the lowest excess mortality which can shield fertility rates in those countries.

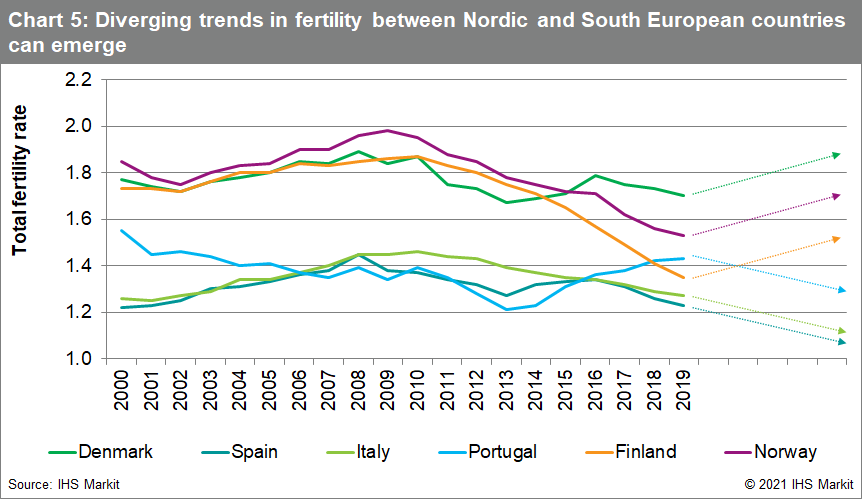

The strength of the recovery in labor markets and diverging pandemic experience can result in diverging trends in some country groups. Unemployment could remain higher in some countries as certain sectors do not regain their pre-crisis capacity or are unable to adapt. This does not bode well for tourism-dependent South European economies, which already have one of the lowest fertility rates in the EU. Spain, Italy, and Portugal have also experienced higher excess mortality and could see their fertility rates deteriorating faster. Highly indebted rapidly aging South European economies would see their pension systems squeezed even more and would become more dependent on labor immigration to sustain potential growth.

On the other hand, more resilient Nordic countries managed to limit damages to their health systems and therefore their economies. They could see more rebound in fertility rates amid strengthening labor markets and a boost to certainty regarding the future. That would be good news for Finland, which has seen the strongest decline in total fertility in recent years as the fertility rate reached all times lows in 2019. However, the risk remains that it could be a temporary spike as economic conditions and personal preferences, which had been driving fertility decline in the past, could prevail again.

Fertility rates fell below the replacement rate in most of the European countries since the nineties. Coupled with a rising life expectancy, we see an impact on population structure as more people are leaving the labor force and fewer are entering.

In addition to the squeeze on pension and health systems, a lower share of working-age people in the total population will have a negative impact on economic growth. Not just from lower numbers but also due to the changing structure of the labor force, which can influence productivity. Research shows, that labor force aging is having a sizable negative effect on European productivity and further deterioration in fertility rates can aggravate the negative impact further.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fhow-permanent-postcovid-decrease-births-europe.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fhow-permanent-postcovid-decrease-births-europe.html&text=How+permanent+will+the+post-covid+decrease+in+births+in+Europe+be%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fhow-permanent-postcovid-decrease-births-europe.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=How permanent will the post-covid decrease in births in Europe be? | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fhow-permanent-postcovid-decrease-births-europe.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=How+permanent+will+the+post-covid+decrease+in+births+in+Europe+be%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fhow-permanent-postcovid-decrease-births-europe.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}