Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Oct 12, 2021

Eurozone inflation: It’s not how high but how long

- This year's unprecedented pick-up in eurozone inflation has further to go given recent strong upward pressure on energy prices.

- Non-energy industrial goods inflation will also rise further as the perfect storm of cost pressures continues to filter through.

- The ECB will terminate its net asset purchases under the PEPP by March 2022, in line with its long-standing forward guidance.

- But the bar for policy rate hikes is set much higher and longer-term inflation prospects will be pivotal in this regard.

High energy

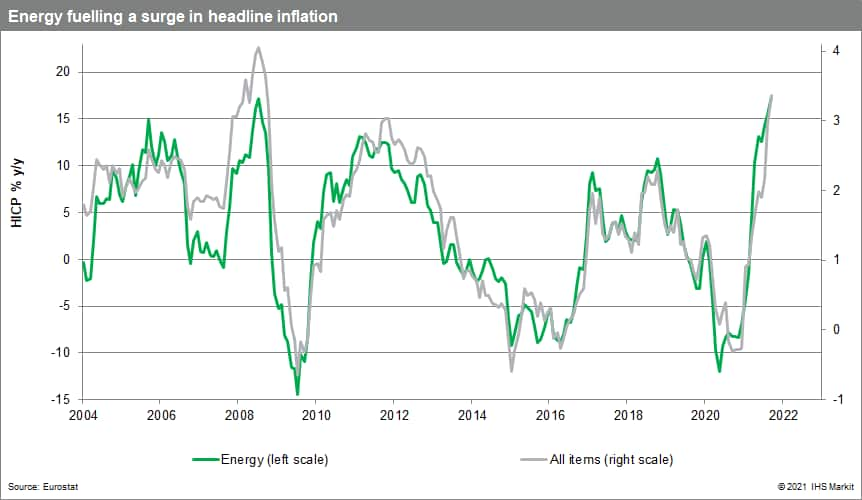

The speed of the acceleration in eurozone HICP inflation year to date is unprecedented. Having jumped from 2.2% to 3.0% in August, Eurostat's "flash" estimate for September showed HICP inflation rising again to 3.4%, the highest rate since September 2008. Inflation has now risen by 3.7 percentage points in the nine months since December 2020 and the upward pressures continue to build.

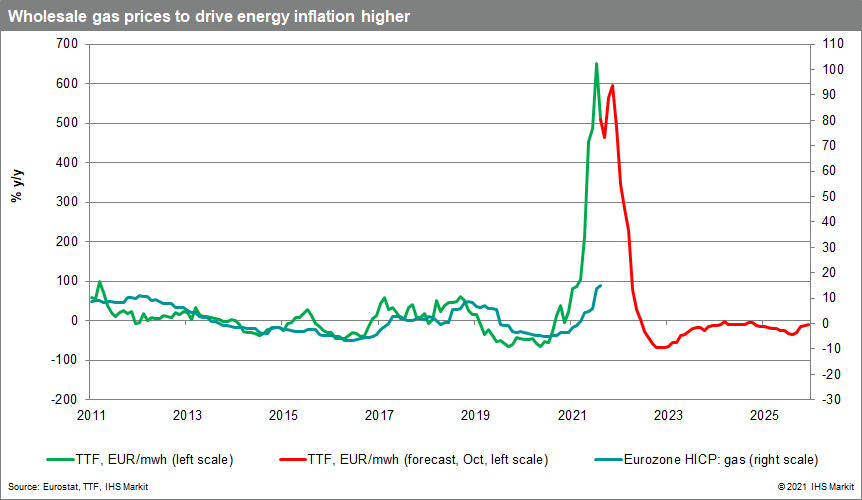

Energy was again a key driver of September's increase, with the inflation rate of 17.4% a record high for the series. Further increases in energy inflation are inevitable in the coming months given the recent surge in wholesale gas prices and the spurt in crude oil prices.

The precise impact of the surge in gas prices on inflation is difficult to gauge due to various complications when trying to assess the pass-through from wholesale to retail. These include a potential squeeze on suppliers' margins, the duration of the wholesale price increases, delays to utility price adjustments and the dampening effects of government subsidies to try to limit the adverse impact on household finances.

Still, given the scale of the rise in wholesale gas prices to date, energy inflation is inevitably going to hit a new record high.

Core inflation less elevated but trending higher

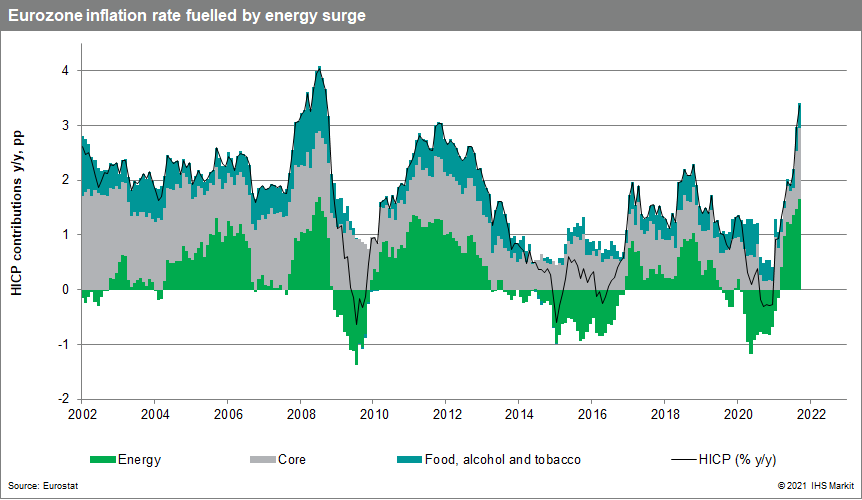

The pick-up in HICP inflation this year is not just about energy. The contribution from core prices has also increased markedly.

The HICP inflation rate excluding food, energy, alcohol and tobacco prices shot up from 0.7% to 1.6% in August, due to COVID-19-related base effects driving up clothing and footwear inflation. It rose less sharply in September, to 1.9%, though this was still the highest rate since November 2008 and again, further near-term increases are likely.

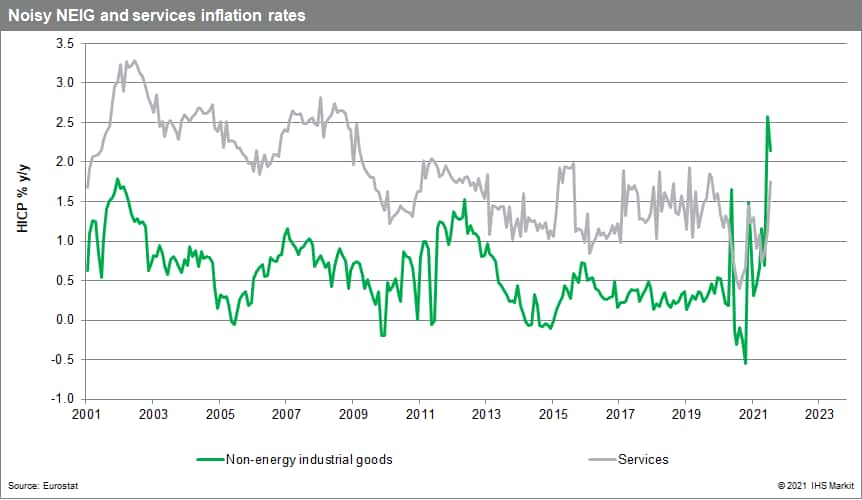

Looking at the core inflation rate's two key components, non-energy industrial goods (NEIG) inflation has been the main source of upward pressure this year.

It surged to a record high of 2.6% in August but partly corrected in September, to 2.1%, as expected, due to the afore-mentioned base effects. Despite September's moderation, the NEIG inflation rate remained 1.6 percentage points above its pre-pandemic rate in February 2020.

Eurozone services inflation jumped from 1.1% in August to 1.7% in September partly due to base effects affecting some of the services prices hit hardest by the pandemic. The trend in services inflation has been rather flat, however, with September's rate only slightly above its pre-pandemic rate (1.6%).

The NEIG inflation rate will rise further due to the ongoing pass-through from firms' higher input costs. These cost increases reflect a perfect storm of upward pressures, including commodity price gains, supply shortages and rising transportation costs, which have all contributed to record high producer price inflation rates.

As services inflation is less sensitive to these externally-driven factors and influenced more by domestic trends in wages and unit labor costs, the more gradual acceleration evident to date is likely to continue. Labor shortages are a potential upside risk.

ECB divisions more prominent

Given the imminent boost from the energy and NEIG rates, HICP inflation is likely to reach a record high over the coming months, surpassing July 2008's 4.1% peak. The prospect of persistently higher inflation is understandably causing some jitters at the ECB.

The two key takeaways from the recent account of its September policy meeting were the increased discussion of upside risks to inflation and the push from some Governing Council members for a more substantial reduction in the pace of the ECB's asset purchases. September's meeting had concluded in favor of only a "moderately lower" pace of net purchases under the pandemic emergency purchase program (PEPP).

Some members highlighted that headline and core inflation had surprised to the upside for some time and questioned whether the ECB's models could be relied upon. They expressed concern about a possible "regime shift". While there was little evidence so far of second-round effects on wage negotiations, they argued that "this time might be different" due to the length and magnitude of the shock to inflation. The duration of the inflation pick-up will be pivotal.

Playing a waiting game

The overall conclusion of the ECB's analysis in September was still that unusually high rates of inflation were largely temporary and that underlying price pressures were building up only slowly. Headline inflation was projected to rise further until end-2021, then fall back in the first half of 2022. Temporary and special effects had continued to have a substantial impact. Measures of longer-term inflation expectations had risen but remained some distance from the 2% target, while inflation options markets signaled a low risk of recent high inflation rates extending into the medium term.

The evolution of this assessment will ultimately determine the future course of ECB policy rates. While internal pressures will continue to build in favor of a less accommodative stance near-term, we continue to expect the most influential members of the Governing Council to be patient for various reasons.

First, inflation and inflation expectations in the eurozone have been uncomfortably low for several years - the recent rise in the latter is actually welcome.

Second, errors with ECB policy tightening in the past (in 2008 and 2011) proved very costly to its credibility and contributed to two severe crises.

Third, its new forward guidance has deliberately set the bar high for the inflation conditions required to prompt policy rate increases. The ECB's guidance also lays out a sequencing for removal of policy stimulus focused initially on asset purchases.

The next two ECB policy meetings on 28 October and 16 December will cement market expectations that net asset purchases under the PEPP will cease by March 2022, in line with the ECB's current forward guidance (and our long-standing baseline forecast).

But the key longer-term signal for policy will be the staff HICP inflation projections for 2023 (just 1.5% in September) and 2024 (December will be the first estimate as the time horizon is extended by one year). We remain skeptical that these new HICP projections, and those for core inflation, will be high enough to trigger a clear shift towards policy rate hikes, though this will not stop financial markets from speculating to the contrary.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-inflation-its-not-how-high-but-how-long.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-inflation-its-not-how-high-but-how-long.html&text=Eurozone+inflation%3a+It%e2%80%99s+not+how+high+but+how+long+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-inflation-its-not-how-high-but-how-long.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Eurozone inflation: It’s not how high but how long | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-inflation-its-not-how-high-but-how-long.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Eurozone+inflation%3a+It%e2%80%99s+not+how+high+but+how+long+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2feurozone-inflation-its-not-how-high-but-how-long.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}