Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Feb 01, 2021

Eco-trade wars: Will they save the rainforest?

France's President Emmanuel Macron stated on 13 January that the country should reduce its dependency on imports of Brazilian soy to avoid contributing to further deforestation of the Amazon. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro and Brazilian Vice-President Hamilton Mourão have responded, denying that soy production contributes to Amazon deforestation.

Macron's position, though unlikely to lead to a significant drop in Brazilian export of soybeans, are demonstrative of a larger trend towards French and European focus on environmental degradation.

Macron's remarks on deforestation risks in the Amazon align with his administration's focus on ecological transition, compounding existing pressure against the EU-Mercosur deal. The French government had already stated in September 2020 that it opposed the EU-Mercosur free-trade deal over concerns about deforestation risks affecting the bloc, particularly in Brazil. Concerns over the environment and focus by EU member governments on the interests of farmers in France and other EU countries such as Belgium and Ireland, along with the opposition in the European Parliament, are likely to continue hindering implementation of the EU-Mercosur agreement, delaying its ratification beyond 2021. In addition, increased attention on deforestation at the EU level would increase the likelihood of MEPs calling for the European Commission to start trade investigations into imports of soy from Brazil over environmental concerns.

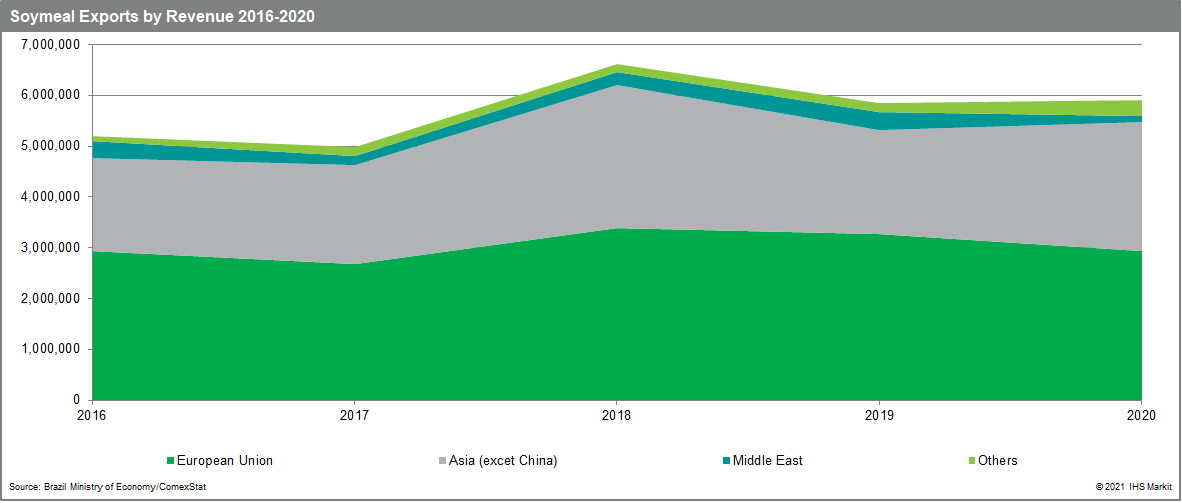

President Macron's comments or a decision by France to boycott Brazilian soy products are unlikely to cause a significant drop in Brazil's exports. The EU receives under 10% of Brazil total soy exports, with 73% going to China. The EU, including France, primarily imports soymeal for animal feed, with the EU accounting for 49.5% of Brazil's soymeal exports. France's share of Brazil's soy market, however, is minimal and Bolsonaro has claimed that Brazil's soy industry would continue to thrive even without France importing any soy products from Brazil.

Brazil claims that soybeans are a straw man, not contributing to the deforestation; regardless environmental controls are being eroded.

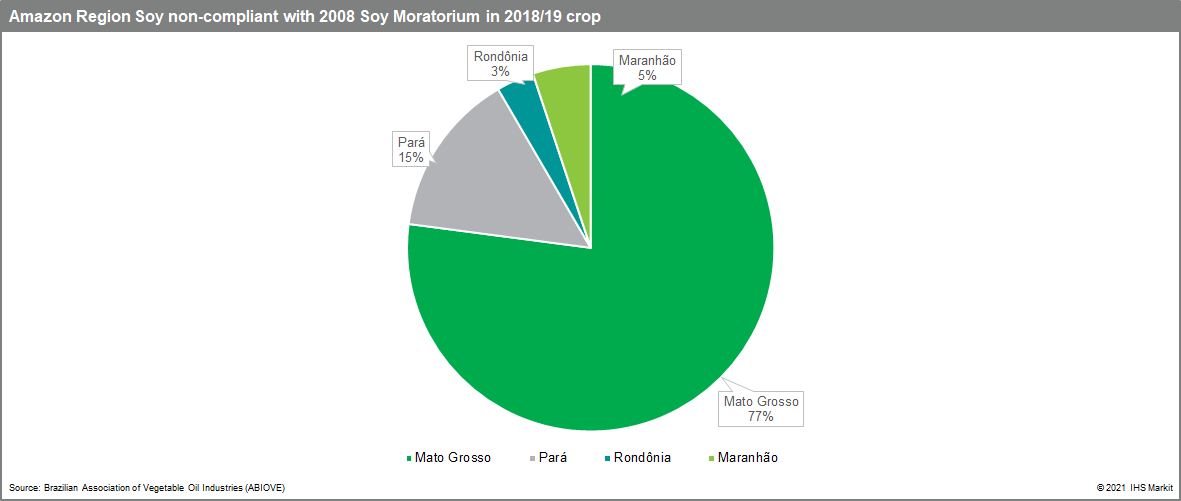

Soy is primarily produced in the Cerrado area rather than in the Amazon region. Data from ABIOVE, the Brazilian Association of Vegetable Oil Industries, show that roughly 50% of Brazil's 2018/19 soy crop was cultivated in the Cerrado region, the single largest soy producing area, and that in this region 93% of the growth in soy crops took place on land cleared before 2013. In 2008, Brazil introduced the Soy Moratorium, an initiative seeking to ensure that soy planted in the Amazon does not contribute to deforestation. A second ABIOVE study analysing the efficacy of this initiative reports that soy cultivation in the Amazon grew from 1.2 million hectares in 2009 to 4.8 million hectares in 2019. However, only 1.5% of this expansion took place on land that had been deforested since 2008, much of this in Mato Grasso states. Although these figures are from an industry trade body and therefore may not be entirely objective, they suggest that despite growing concerns from environmental organisations about Brazil's environmental policies, soy cultivation is not the major contributor to Amazon deforestation.

Despite Brazil's continued participation in the Paris Climate Agreement and formally rigorous environmental laws, President Bolsonaro's actions demonstrate ideological opposition to environmental controls. Brazilian law states that, in the Amazon region, agricultural producers must preserve 80% of all native forest on their land, using only 20% of land for cultivation. However, Bolsonaro pledged in 2019 to open the Amazon to agribusiness and mining, while Environment Minister Ricardo Salles has sought to deregulate environmental practices, claiming that this will reduce poverty in the region. As a result, enforcement of existing regulations had been weak, giving scope for soy grown by unregistered growers operating in the Amazon and contributing to deforestation to enter agribusiness supply chains. Bolsonaro is unlikely to seek to combat this, as he has also proposed defunding the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), the administrative branch of the Ministry of the Environment that implements environmental regulations.

Pressure to take environmental risks seriously are not solely coming from governments, but increasingly shareholder activists as well.

Even without a drive for official EU regulation, companies face growing pressure from NGOs, consumers and ESG-oriented shareholders to demonstrate deforestation-free supply chains for agricultural products, with increased focus on environmental sustainability threatening Brazilian exports. High-profile comments such as those by Macron are likely to encourage shareholder activism, particularly by French ESG funds (such as Amundi and AXA, already high-profile exponents of shareholder activism), increasing pressure on major food companies to prove that supply chains are ESG-compliant, even without regulatory changes. ESG compliance also threatens to generate increased operating costs, given the limited enforcement of regulations in Brazil. The association between soy and deforestation - even if possibly unjustified - increases reputational risk for Brazilian exports of soymeal to the EU, raising the likelihood that French and/or other European farmers, meat and dairy producers halt imports of soymeal from Brazil over concerns about their products causing deforestation or damage to their own market reputations. Macron's stance also increases the likelihood that environmental lobby groups will have improved access to government officials to discuss wider regulatory initiatives.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fecotrade-wars-will-they-save-the-rainforest.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fecotrade-wars-will-they-save-the-rainforest.html&text=Eco-trade+wars%3a+Will+they+save+the+rainforest%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fecotrade-wars-will-they-save-the-rainforest.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Eco-trade wars: Will they save the rainforest? | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fecotrade-wars-will-they-save-the-rainforest.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Eco-trade+wars%3a+Will+they+save+the+rainforest%3f+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fecotrade-wars-will-they-save-the-rainforest.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}