Demographics in Europe: Which countries are poised to succeed

- Life expectancy has risen, but that trend has been accompanied by declining fertility rates, triggering a rapid ageing of the population across much of Europe.

- Although Europe's demographic shift may be positive in terms of environmental sustainability, it has significant implications for the continent's economic health.

- Governments will need to take steps toward long-term sustainability, through investments in education and training, reforms of the pension and healthcare systems, and efforts to boost labour force participation.

The United Nations (UN) 2019 population forecast indicates that all but 14 European countries will experience declines through 2050. While Western Europe will experience most of that growth, many countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) are projected to undergo a significant drop, with especially dramatic population declines in Lithuania, Bulgaria, Latvia, and Ukraine.

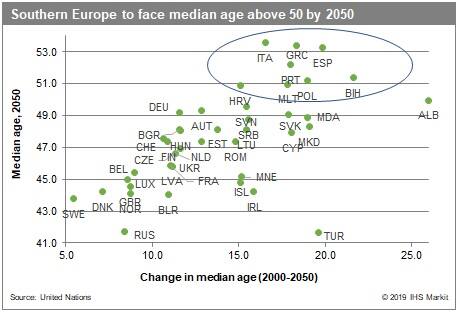

Even where populations continue to expand, shrinking birth rates and improved longevity are triggering a rise in the median age. The UN projects that eight southern European countries (Italy, Greece, Spain, Portugal, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Malta, Croatia, and Albania) as well as Poland will have a median age of 50 or more by 2050.

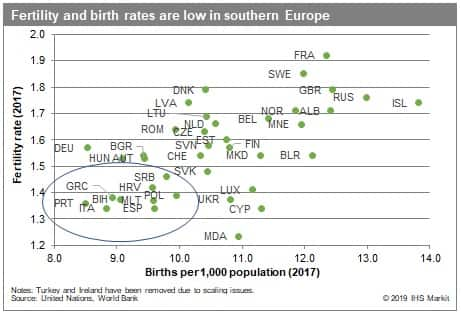

A high projected median age tends to correlate with low fertility rates, which have dropped in Western Europe since the 2008-09 financial crisis amid financial uncertainty and rising housing costs, forcing countries to rely on immigration to boost the population. Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Liechtenstein were the only West European countries to see a higher average fertility rate in 2015-17 than in 2007-09. In contrast, some CEE countries have seen a significant strengthening of fertility rates as living standards improve, with Russia, Lithuania, Latvia, Hungary, and Belarus reporting especially marked gains. Still, 2017 World Bank data indicate that fertility rates remain below the replacement level throughout Europe.

Economic implications of demographic change

Although positive for the environment, Europe's demographic shift has negative implications for economic growth, as the population decline is matched by steep reductions in the size of the labor force. The EU's population aged 15-64 is already declining, falling 1.6% from its 2010 peak by 2018. The bloc's working-age population is projected to drop another 15.7% between 2018 and 2050.

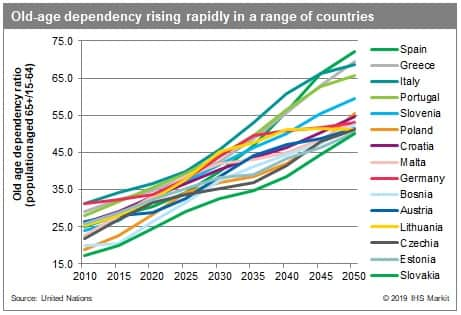

The combination of improved longevity and low fertility rates means that demographic pyramids are shifting, as the proportion of younger, resource-generating residents declines and the share of older, resource-consuming residents increases. Rising old-age dependency ratios mean that the working population is forced to support a growing number of retirees. The UN projects that several southern European countries (Spain, Greece, Italy, and Portugal) will face old-age dependency ratios above 65% by 2050, marking a steep increase over 2010 levels of approximately 30% or less.

The population's ageing is already putting pressure on public finances, straining the healthcare and pension systems and endangering Western Europe's welfare model. The situation is expected to worsen over the longer term. Increased fixed expenditures on social welfare will limit room for investment in innovation, thereby hindering growth in international competitiveness.

What can be done to relieve the demographic burden?

While there is no universal panacea for the continent's demographic problems, certain steps can be taken to ease the challenges and prevent the situation from worsening. Countries that are now behind in dealing with the ageing population can learn from those that are more advanced, helping to promote a sustainable future.

Pension systems represent one prominent area for reform. According to the 2018 Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index (MMGPI), which evaluates the pension systems in 34 countries worldwide, the Netherlands, Denmark, Finland, and Sweden rank among the five best countries globally in which to retire since pensioners continue to enjoy a high quality of life. Moreover, the four countries' pension systems are viewed as sustainable, in contrast to those of other West European countries such as Austria, Italy, Spain, France, Ireland, and Germany.

The only Emerging Europe country included in the MMGPI is Poland, whose pension system is viewed as neither adequate nor sustainable. Indeed, the social security systems in most of Emerging Europe have not evolved enough to provide sufficient resources to pensioners, many of whom are living in poverty or are forced to supplement their meagre retirement incomes by working in the shadow economy.

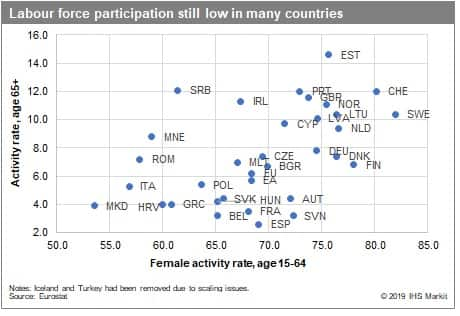

Aside from pension and healthcare reforms, demographic challenges may also be alleviated by increasing the size and effectiveness of the labor force. This can be accomplished by boosting activity rates among the female and elderly populations, improving education and training (including adult learning), raising investment in new technology, and encouraging immigration (and return migration) while ensuring rapid integration into productive society. Importantly, Sweden has shown that higher female labor force participation rates may go hand in hand with higher fertility rates if steps are taken to invest in affordable childcare and to encourage flexible work arrangements.

Europe is not alone

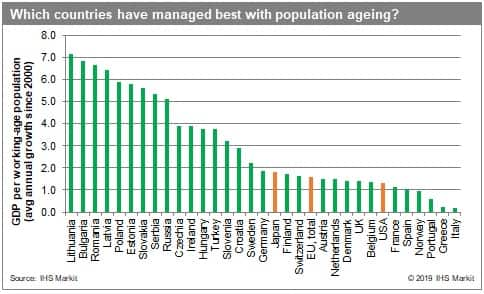

In measuring the success of demographic policies, it is important to keep in mind the distortions created by declining populations. For example, Japan's real GDP has risen only about 15% since 2000 (less than 1% per year), making it one of the world's least dynamic economies. However, growth looks considerably stronger given that Japan's working-age population has been shrinking steadily since 2000. The country's growth rate per working-age population has been close to 2%, above the figures for both the EU and the US.

Within the EU, the growth rate per working-age population has been much faster among Emerging European countries. Among advanced economies, Ireland, Sweden, and Germany have performed best, while Italy, Greece, and Portugal have shown very poor results, signaling urgent need for change.

Despite the grim outlook for many European countries, the extensive list of policy tools that governments have at their disposal underscores the uncertainty of long-term forecasting, as there are many moving parts. Indeed, the outlook could improve significantly with the right policy mix.