Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Oct 08, 2021

CRIM for sectoral differentiation: Onshore vs Offshore LNG projects in Mozambique

When investing overseas, it is key to consider the nuances in risk across different sectors. Sovereign indicators (such as government bond yields, CDS spreads, or government bond ratings) are poor proxies for the risks associated with a private company doing business in a country and cannot reflect the peculiarities of different sectors. As the following case study will show, we will see how two energy companies have taken opposite directions for their liquefied natural gas (LNG) operations in Mozambique.

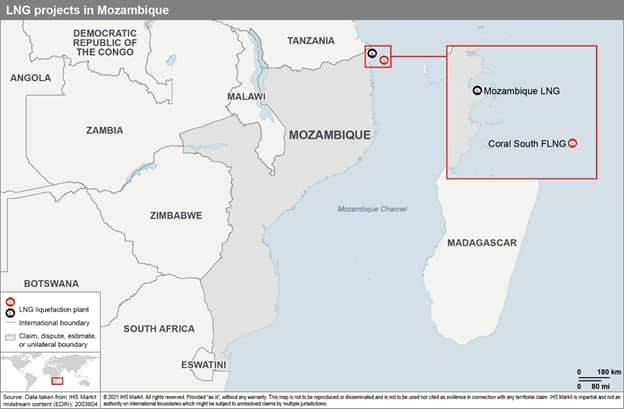

In April 2021, a European energy conglomerate declared force majeure on its USD20 billion onshore Mozambique LNG project (see map below) following attacks in the previous month by Islamic State-affiliated insurgents on the town of Palma. It had bought an operating stake in the project in 2019, which was supposed to start exporting 13 million tons of LNG per year starting from 2024.

At around the same time, another energy company confirmed that development work in the Coral South project, the first significant offshore LNG project launched in Mozambique, was 80% completed. In contrast to the onshore project, the company confirmed that first production was still expected in 2022, despite ongoing unrest in the Cabo Delgado province. The project extracts gas via six subsea wells located in the southern part of the Coral field that will be linked to floating facilities that will liquefy 3.4 million tons a year for export.

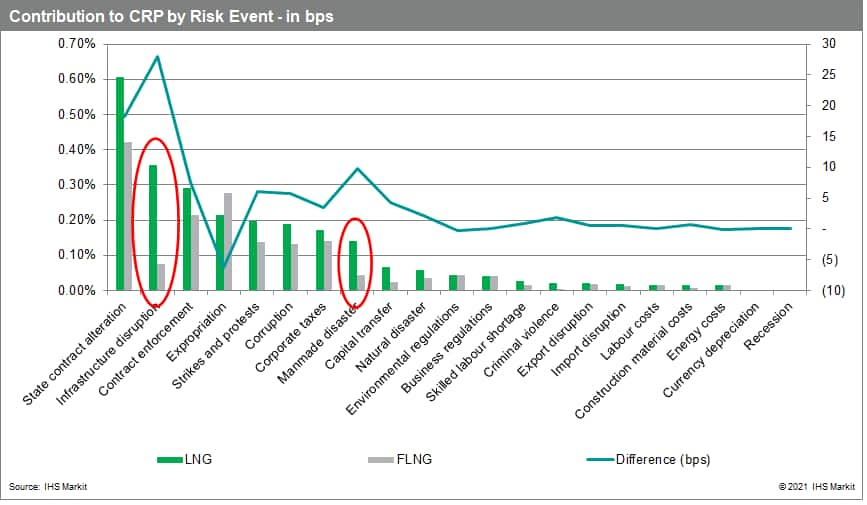

The contrasting developments of these two LNG initiatives highlight the weakness of assessing country risk using sovereign debt indicators that assign a single risk premium to all investments in a country. The Country Risk Investment Model (CRIM)-computed Country Risk Premiums for the Onshore LNG and Offshore LNG sectors (as of August 2021) are respectively 2.50% and 1.67%. Interestingly, 38 basis points out of the 83 bps total difference in CRPs (detailed in the chart below) is due specifically to the infrastructure disruption (risk of failure of transport, power, and other networks) and manmade disaster (risk of interstate war, insurgency and civil war, terrorism) risk factors. This is because offshore LNG developments are naturally much less exposed to the risks of insurgency, terrorism, and other disruptions that can hinder the movement of workers and equipment for long periods of time.

A thorough and quantitative understanding of country risk from the outset would have allowed the decision-makers to more fully evaluate the exposure to security and other operational risks while at the same time target specific mitigation strategies - for example budgeting for additional security provisions and risk transfer for political violence - which would have avoided, or at least reduced, the impact of the force majeure declaration.

The CRIM is a proprietary tool that quantifies country risk for investment projects. It measures expected financial losses from future developments in cash-flow terms, evaluating bottom-up the potential impact of 20 risk sources that include the threats of manmade disaster and infrastructure disruptions, amongst other political, economic, legal, fiscal, operational, and security events.

By analyzing the impact of specific risk sources using a bottom-up granular approach, we get a much more accurate and insightful picture of country risk that will also support bespoke mitigation planning. One-size-fits-all proxies of country risk do not capture the nuances related to different sources of country risk and can easily lead to companies either investing in projects that are too risky or missing out on profitable opportunities. A granular view of all sources of risk is paramount to making the best capital investment and allocation decisions.

For more on this story, listen to our podcast: How complete is your risk profile? Looking at LNG projects in Mozambique and Tanzania

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcrim-for-sectoral-differentiation-onshore-vs-offshore-lng-proj.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcrim-for-sectoral-differentiation-onshore-vs-offshore-lng-proj.html&text=CRIM+for+sectoral+differentiation%3a+Onshore+vs+Offshore+LNG+projects+in+Mozambique+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcrim-for-sectoral-differentiation-onshore-vs-offshore-lng-proj.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=CRIM for sectoral differentiation: Onshore vs Offshore LNG projects in Mozambique | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcrim-for-sectoral-differentiation-onshore-vs-offshore-lng-proj.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=CRIM+for+sectoral+differentiation%3a+Onshore+vs+Offshore+LNG+projects+in+Mozambique+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcrim-for-sectoral-differentiation-onshore-vs-offshore-lng-proj.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}