Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Feb 24, 2021

Civil unrest correlations

A recent study by the University of Cambridge stated 2019 saw the "highest level of democratic discontent on record". Dissatisfaction with democracy in developed countries had increased from a third to half of all citizens over the last 25 years. The last two years have also seen several large-scale and disruptive protests - including in the special administrative region of Hong Kong; Santiago, Chile; political violence in the US, Thailand, Belarus, India, and now in Myanmar; anti-corruption protests in Lebanon; anti-racism protests around the world; anti-lockdown protests in several countries. Broad trends in political sentiment, it seems, are linked to concrete threats to personnel and assets.

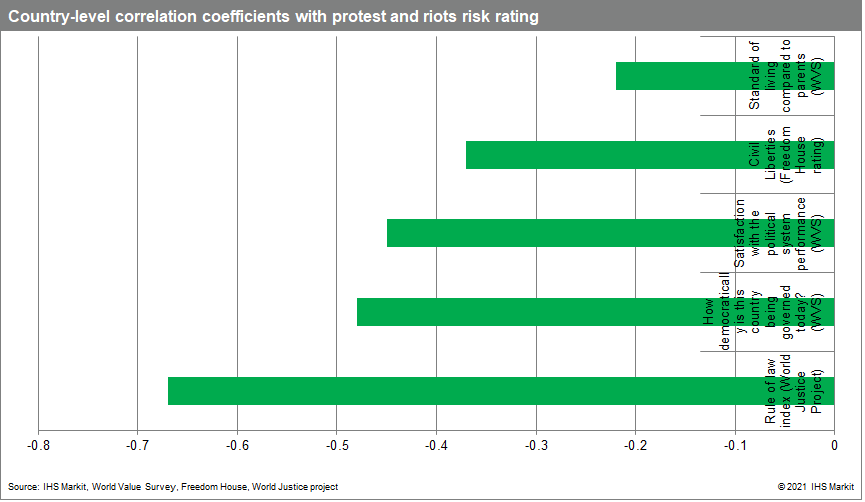

Here we look at correlations between measures of political dissatisfaction and our country-level protests & riots scores. Our protest & riots score is well-correlated with several widely respected survey measures on social themes that have a bearing on long-term, strategic security concerns. Frustrations with political institutions and dissatisfaction with the depth of democratic governance, for example, are correlated with high risks of civil unrest. Such high-level correlations are unsurprising and of course cannot capture the complexity of local dynamics that drive civil unrest. But five country-level examples below show how these correlations can indicate which assets and personnel are at risk during periods of unrest - extrapolating from strategic to tactical.

The data

Our Economics & Country Risk scores measure the risk of protests and riots over a 12-month time horizon. The scores are based on granular local dynamics assessed by our country risk experts. We combined these risk scores with survey data from the World Value Survey (WVS) about satisfaction with the political system and other indicators that measure civil liberties (Freedom House) and the rule of law (World Justice Project). The WVS is based on 72,879 representative respondents from 50 countries interviewed between 2017 and 2020. To evaluate respondents' assessment of democratic governance in their country we use the following WVS question: "How democratically is this country being governed today?" (answered on a scale from 1 to 10). Interestingly, this subjective assessment of respondents is not correlated with objective measures of democracy from the PolityProject or Freedom House. WVS respondents in Tajikistan, China and Vietnam, for example, provide high average ratings for democratic governance in their countries but the Polity V rating on institutionalized democracy for those countries is extremely low. There are several plausible reasons for this, including respondents interpretation of key terms like 'democratically', relative improvement in governance in the years preceding the survey, and in some cases tacit coercion when answering. Overall, we assume respondents' answers are an acceptable proxy for overall 'satisfaction' with the political system under which they live.

To measure dissatisfaction with the political system we analyse the following WVS question: "How satisfied are you with how the political system is functioning in your country these days?", (also answered on a scale from 1 to 10). This question is unrelated to the nature of the political system and addresses how respondents perceive the performance of the political system. The individuals' understanding of "the political system" and its performance might vary across countries.

Correlates of civil unrest

We find that the protests and riots risk rating is highly correlated with the rule of law index (-0.7), the respondents' perception of democratic governance in their country (-0.5) and the respondents' satisfaction with the political system performance (-0.4).

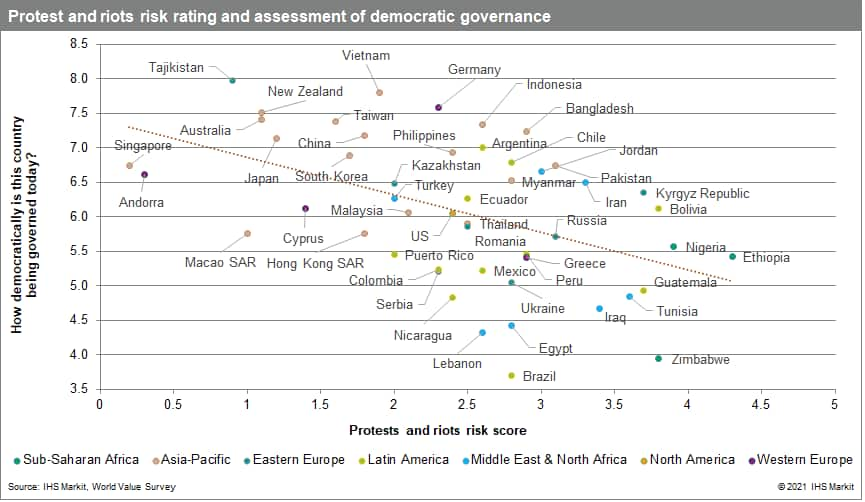

In countries where citizens perceive a lack of democratic participation and representation, there is a greater risk of protests and riots. Citizens in the Asia-Pacific region report that their countries are more democratically governed on average than those in other regions, yet within the region there is still a higher degree of variation in the risk of protests and riots. Of all countries in the WVS dataset, Singapore records the lowest protests and riots risk score (at 0.2), yet in Pakistan where citizens report roughly the same levels of democratic governance, the protests and riots risk score is far higher (at 3.1).

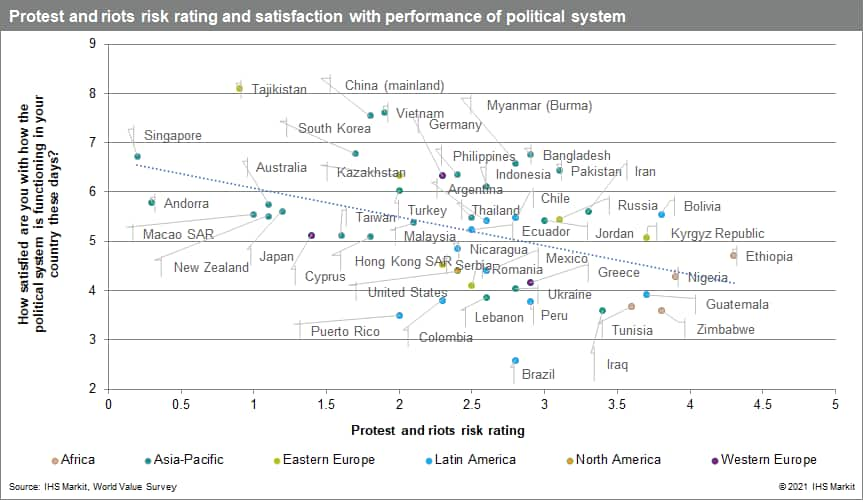

In countries where respondents are highly satisfied with the performance of their political system the protests and riots risk rating is lowest. High levels of dissatifcation as for example in Brazil, Iraq or Zimbabwe are correlated with a high risk or protests and riots over the next 12 months. Satisfaction with the political system is highest in Asia and Europe while respondens in Latin America, the Middle East and Africa are more critical.

Country cases

The correlations above are often - but not always - reflected at a country-level and survey data can indicate in concrete terms the assets and personnel at risk during periods of civil unrest. Five examples from around the world show this:

- Pakistan (2018 data)

Respondents in Pakistan in 2018 showed more satisfaction in the country's political system (6.4 out of 10) than respondents in more established democracies in the region, like Japan (5.6), Australia (5.7), New Zealand (5.5) and India (6.1). But Pakistan had the highest protest and riot risk score in Asia-Pacific that year at 3.1, driven partly a contentious parliamentary election in August but mostly by conservative Islamist groups agitating over blasphemy issues. That Pakistani respondents were most likely in the region to consume social media news demonstrates the wide scope for misinformation triggering disruptive unrest over polarising issues, despite overall satisfaction in political institutions.

- Iraq (2018)

Iran's decision to cut off electricity supplies to Iraq led to protests across southern Iraq in July 2018, the most serious and long-lasting of which took place in Basra province. The perception that political elites, particularly Shia Islamist political parties and associated militias, had vastly enriched themselves at the expense of the local population increased local resentment towards Islamist parties (reflected in Iraq's corruption score of 6.5). Indeed, Iraqi respondents were largely unsatisfied with the performance of their political system, which is dominated by these parties (3.27 out of 10). This was evident on 6-7 September 2018 when political party offices were burned. Protestors also set alight the Iranian Consulate in Basra.

- Ethiopia (2020, 2018)

Living in a democratically governed country was extremely important to Ethiopians in 2020 - when a civil conflict with political and ethnic drivers broke out in Tigray (9.5 on a scale of 1 to 10). Ethiopia had scored only 3 (on a scale from 1 to 10) for institutionalized democracy in the Polity V rating. Ahead of the 5 June 2021 general elections, from which multiple major opposition parties have claimed they are being unfairly excluded by the government, protests will regularly include participants perpetrating politically- and ethnically-targeted violence against state and party offices, local individuals, and locally-owned homes and businesses.

- Chile (2019)

Chile leads Latin America in civil liberties and satisfaction with democracy, according to international ratings. Its main social challenge has been deep economic inequality - Chile's Gini coefficient of incomes is 44.4, higher than most 'high income' countries (2017 World Bank data). An increase in subway fares in Santiago triggered protests in October 2019 that quickly coalesced into demands to change the state's neoliberal economic model. Six weeks of nationwide protests, including arson on metro stations and public buses and looting of retail stores, caused more than USD4.5 billion in damage. The process to re-write the constitution - a key demand - will start with elections this April and is likely to significantly reduce civil unrest in 2021 - potentially helping to vindicate Chileans' confidence in their political institutions.

- Kyrgyzstan (2020)

Disputed general elections in October 2020 triggered widespread protests in Kyrgyzstan. But Kyrgyz survey responses indicate relatively strong confidence in government (2.5 on a scale from 4 to 1) democratic governance (6.4 out of 10), and households' satisfaction with their financial situation (7.5 out of 10). Indeed, the costliest commercial damage was perpetrated by organized criminal groups targeting mining companies across the country with break-in attempts, theft and arson. Early presidential elections on 10 January resulted in a landslide victory for Sadyr Zhaparov, whose populist policies are likely to polarize and test Kyrgyz satisfaction in national political institutions - likely increasing the frequency of civil unrest.

Civil unrest in the coming years will be driven by a range of issues, including livelihood grievances if governments struggle to steer their economies towards post-pandemic recovery. Understanding the nuances of those drivers will indicate which assets and personnel will be at risk.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcivil-unrest-correlations.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcivil-unrest-correlations.html&text=Civil+unrest+correlations+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcivil-unrest-correlations.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Civil unrest correlations | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcivil-unrest-correlations.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Civil+unrest+correlations+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fcivil-unrest-correlations.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}