Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Oct 06, 2022

Brazil’s first-round election results increase risk of gridlock in Congress, posing hurdles to fiscal consolidation

In the most polarized election since the end of the military dictatorship in 1985, former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the leftist Workers' Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores: PT) and incumbent far-right President Jair Bolsonaro of the Liberal Party (Partido Liberal: PL) came first and second, respectively, in the first round of voting on Oct. 2.

The contest will move to a second round on Oct. 30 as neither candidate obtained the 50% required to win outright. The first-round outcome is likely to buoy Bolsonaro, whose showing was better than polling had indicated. Lula will seek to capture support from the parties that finished third and fourth, which are more likely to back him than Bolsonaro.

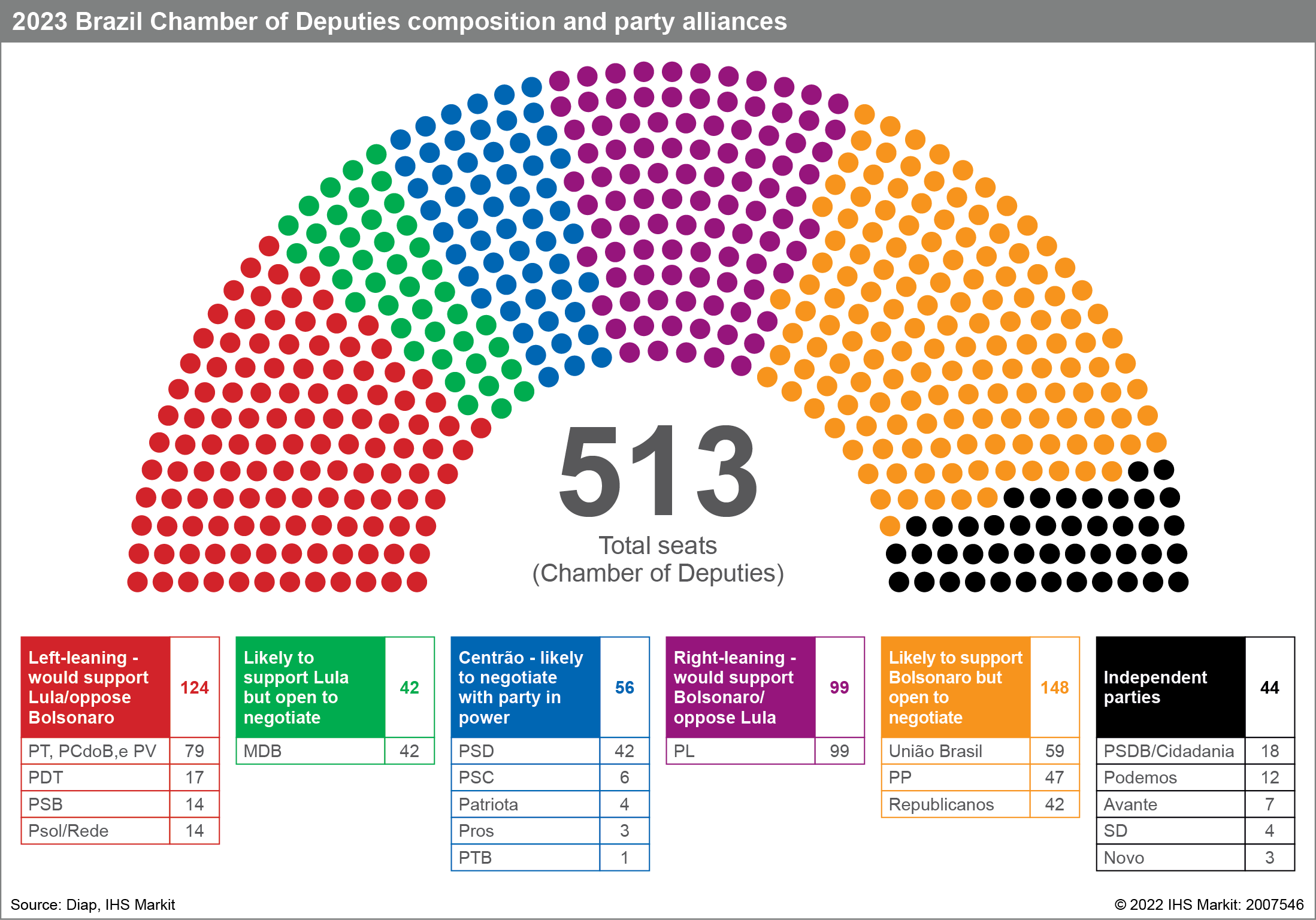

The likely need for a wide coalition, regardless of who wins the election, will prevent sharp changes in policy. No party will command a majority in either the senate or the chamber of deputies. The new government will need to negotiate alliances with multiple political parties to progress its agenda.

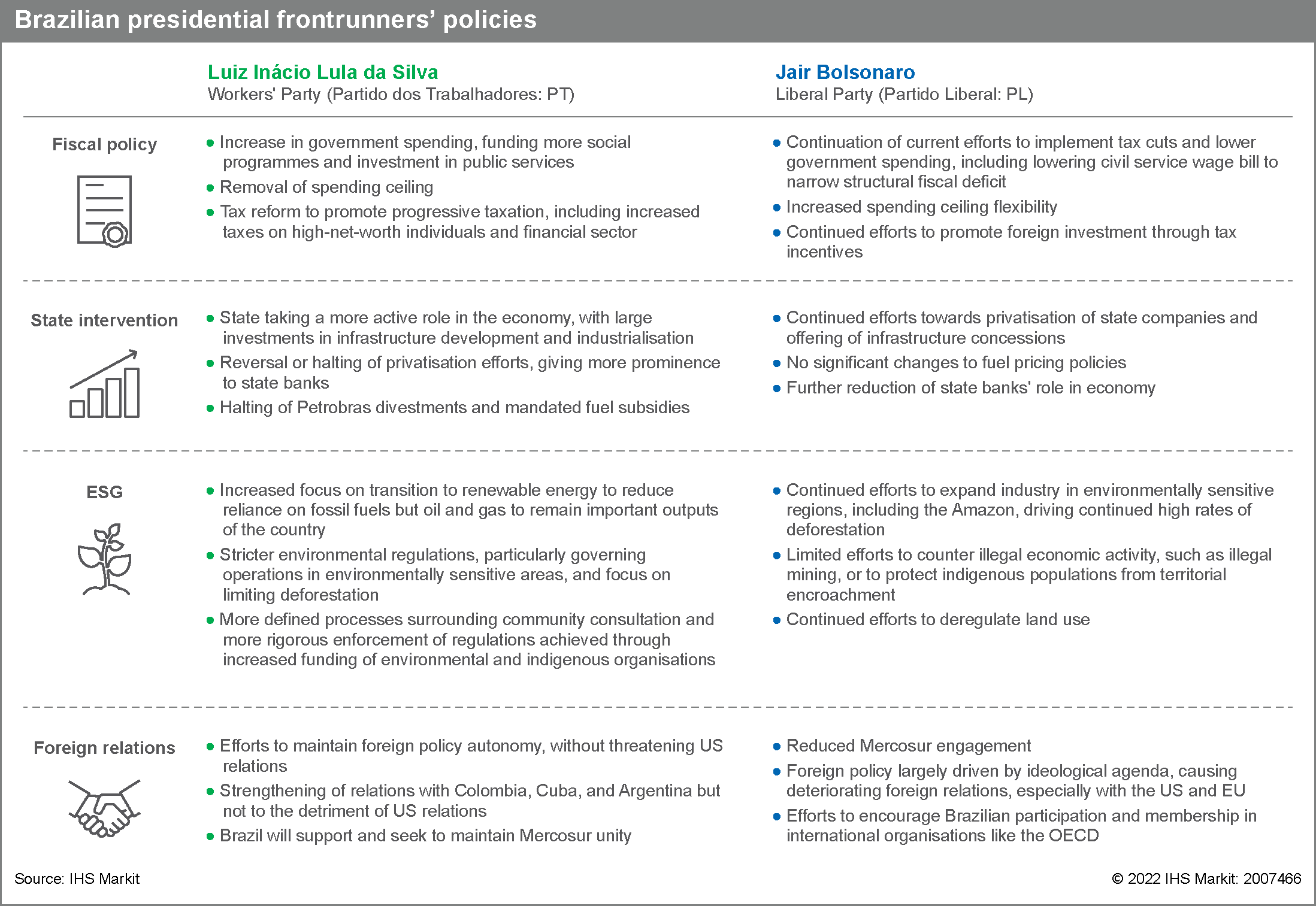

Lula has stressed that during his time in office (2003-10), Brazil enjoyed strong growth, poverty decreased, and the fiscal deficit and public debt declined markedly. Lula has not specified how he would reduce Brazil's large current structural fiscal deficit or contain the expansion in public debt (78% of GDP). Scope to support poverty-reduction schemes and increase public capital investment, as promised by Lula, is thus very limited.

Budget implications

Bolsonaro has embarked on electorally driven expenditure and implemented tax cuts that have worsened the country's fiscal deficit position.

Each candidate has pledged to either remove or amend the cap on the federal budget, in place since 2017. Unless policy direction changes within the coming year, Brazil's fiscal and public debt positions will worsen significantly under either candidate.

Bolsonaro's strengthened position limits the risk of unrest and protests surrounding the first round. This risk will revive if he is narrowly defeated in the second round.

The Brazilian economy has proven resilient. GDP figures for the second quarter were stronger than expected improving prospects for 2022. However, if the global economy entered a recession, the country would face an extremely challenging environment, which would be compounded by political polarization and hurdles posed by a highly fractured Congress.

Political gridlock would further delay the approval of much-needed reforms. This could lead to policy uncertainty detrimental to business sentiment and investment, exacerbating the economic downturn.

Threat of recession

A recession would represent a significant threat for the next government. Brazil's political history shows that governments that experienced a recession either were unable to finish their terms or failed to be re-elected.

Brazil is less well positioned than in the two prior recessions to resist the impact of the recessionary economic slowdown in the U.S. and China. Rising interest rates will discourage consumption and domestic corporate investment, exacerbating the impact of potentially lower export demand.

The high projected inflation rate implies a deterioration in real wages, dampening the prospects for household consumption. Credit growth is already constrained as Brazilian consumers have borrowed by more than average during the past two years because of the COVID-19 pandemic and are now highly leveraged.

The political willingness to introduce investment incentives and improve the business environment is limited, as Brazil lacks fiscal flexibility and may need to fund additional social spending commitments after the 2022 presidential election.

The 'ceiling' and the 'golden rule'

The next government needs to show commitment to fiscal sustainability, suggesting that it must adhere to the spending "ceiling" and the "golden rule."

The "ceiling" limits the growth of federal expenditures to keep pace with inflation (of the previous year). This has been a major factor controlling the expansion of the fiscal deficit over the past five years.

The "golden rule" forbids the government from incurring debt to pay current expenses: Additional debt should only be allocated to capital outlays.

Failure to stick to these two policies, which is not unlikely, would be damaging for business confidence and investment and thus future growth.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbrazils-firstround-election-results-increase-risk-gridlock.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbrazils-firstround-election-results-increase-risk-gridlock.html&text=Brazil%e2%80%99s+first-round+election+results+increase+risk+of+gridlock+in+Congress%2c+posing+hurdles+to+fiscal+consolidation+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbrazils-firstround-election-results-increase-risk-gridlock.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Brazil’s first-round election results increase risk of gridlock in Congress, posing hurdles to fiscal consolidation | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbrazils-firstround-election-results-increase-risk-gridlock.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Brazil%e2%80%99s+first-round+election+results+increase+risk+of+gridlock+in+Congress%2c+posing+hurdles+to+fiscal+consolidation+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fbrazils-firstround-election-results-increase-risk-gridlock.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}