Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Dec 22, 2020

Africa conflict series: Sahel

This is the second in a series of three reports examining key conflicts in Africa in 2021. The first, on Ethiopia, ran on 11 December.

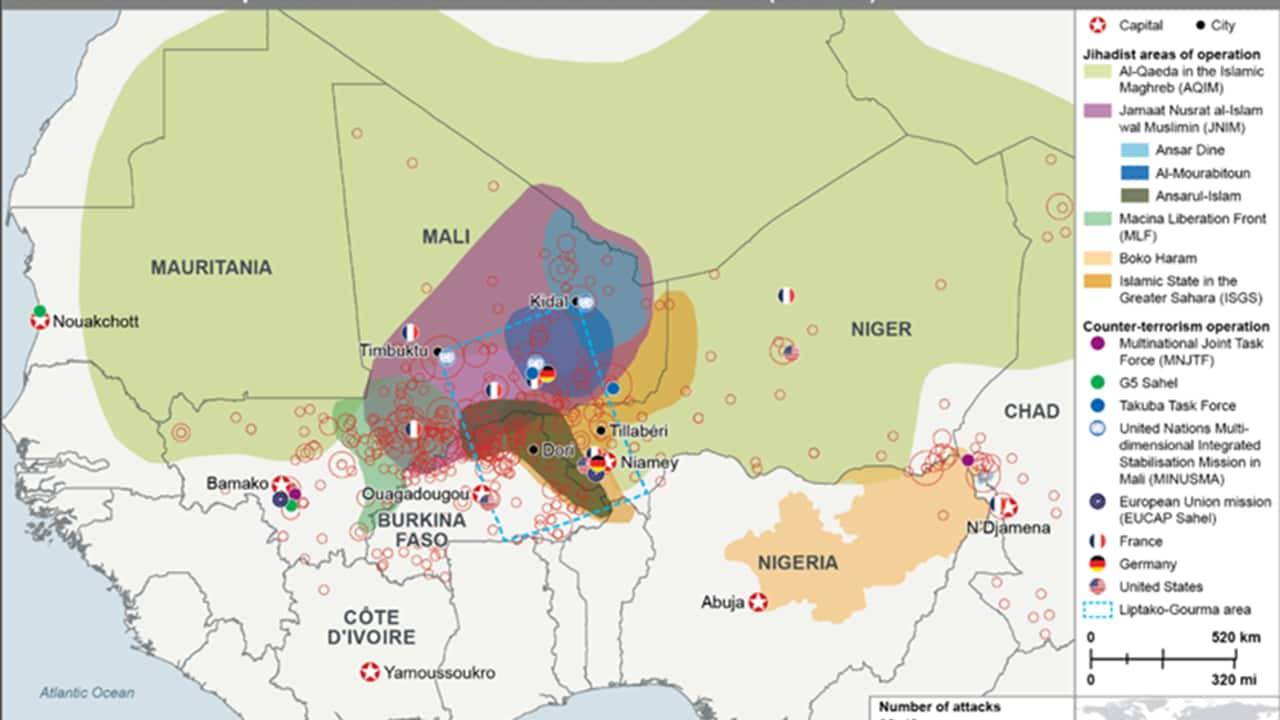

The Sahel region has witnessed an upward trend of jihadist attacks since 2017 with the merger of several jihadist groups under the umbrella of Jamaat Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), which has pledged allegiance to Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). This is despite counter-terrorism and peace building efforts engaged by Sahel countries and a number of international partners, most notably France since 2013.

JNIM attacks are very likely to expand deeper into Burkina Faso and Niger around the Liptako-Gourma tri-border area.

The most prominent hotspot for jihadist and militia activity is tri-border area between Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, known as the Liptako-Gourma tri-border area, which has become the epicenter of jihadist activity in the Sahel. However, through 2020, the insurgency has been spreading southwards towards Burkina Faso and to a lower extent Niger, where jihadists have exploited poor intelligence and weak security forces. Notable attacks have occurred in northern, eastern, and central Burkina Faso, mainly targeting military, police, mining, and humanitarian workers, usually involving improvised explosive device (IED) followed up by small-arms assaults by jihadists.

Deteriorating citizen safety, political instability and local grievances stemming from poor governance and low economic opportunity will likely support the jihadist expansion.

Local grievances over chronic and long-lasting issues such as poverty, political and security instability are likely to continue being key drivers of insecurity. There is a correlation between the areas with inter-communal rivalries and the number of jihadist attacks. Hotspots of both inter-communal violence and attacks in Mali include northern cities in and around Kidal, Gao, Timbuktu where the leader of the jihadist group Ansar Dine, Iyad ag Ghaly, has been advocating for the creation of an Azawad state. Ethnic conflicts between the Dogon (sedentary farmers) and nomadic Fulani are likely to continue in the centre of Mali, around Mopti. In Burkina Faso, land conflicts between the dominant Mossi and second largest group, the Fulani, is facilitating jihadist recruitment of Fulani. Niger has been more successful at managing its ethnic conflicts compared with Mali and Burkina Faso, probably because successive governments have been more inclusive. Current hotspots of violence in the Tillaberi, Tahoua regions in the west and Diffa in the southeast, largely due to Islamic State activity.

Low likelihood of dialogue between JNIM and governments resulting in a ceasefire in 2021.

The is growing interest in dialogue from the JNIM and the governments of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. Even if these are initiated in 2021, it very unlikely that insurgents will agree to a ceasefire. More likely is an intensification of attacks to improve their negotiating position. There is likely to be growing rivalry between the Islamic State in the Grand Sahara (ISGS) and AQIM-affiliated JNIM. This will likely result in attempts to assert their respective leaderships by mounting attacks on security forces and government targets, as well as kidnaping foreigners. France is likely to be faced with growing regional hostility given its opposition to dialogue and its military-centric counter-insurgency strategy.

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fafrica-conflict-series-sahel.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fafrica-conflict-series-sahel.html&text=Africa+conflict+series%3a+Sahel+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fafrica-conflict-series-sahel.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=Africa conflict series: Sahel | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fafrica-conflict-series-sahel.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=Africa+conflict+series%3a+Sahel+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fafrica-conflict-series-sahel.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}