Customer Logins

Obtain the data you need to make the most informed decisions by accessing our extensive portfolio of information, analytics, and expertise. Sign in to the product or service center of your choice.

Customer Logins

BLOG

Apr 20, 2021

USMCA - an enhanced framework for trade within North America

Main findings

- USMCA, which went into force in July 2020, replaced NAFTA and is its successor

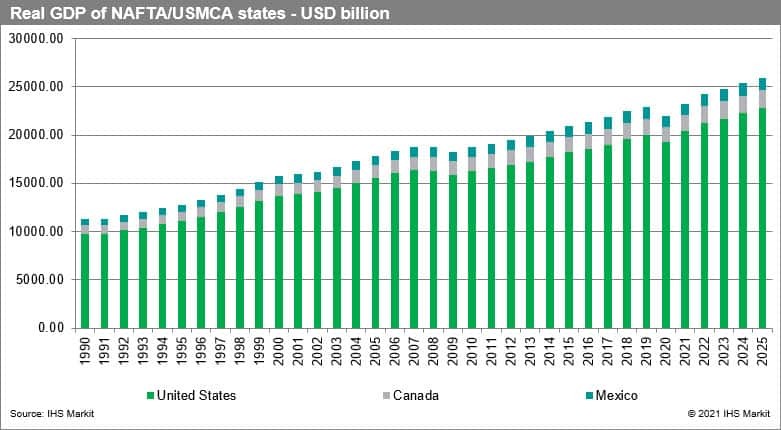

- Real GDP of USMCA countries in 2020 was equal to USD 24.2 trillion (30% of global GDP) - larger than the GDP of EU27 or China

- Since the ratification of NAFTA, merchandise trade between the three NAFTA/USMCA partners increased from around USD 290 billion in 1993 to over 1.27 trillion in 2019

- NAFTA brought about significant effects in terms of trade and establishment of North American production chains with interesting effects on the location of activities in particular on the U.S. Mexico border and within Mexico; welfare effects were surprisingly smaller than initially expected

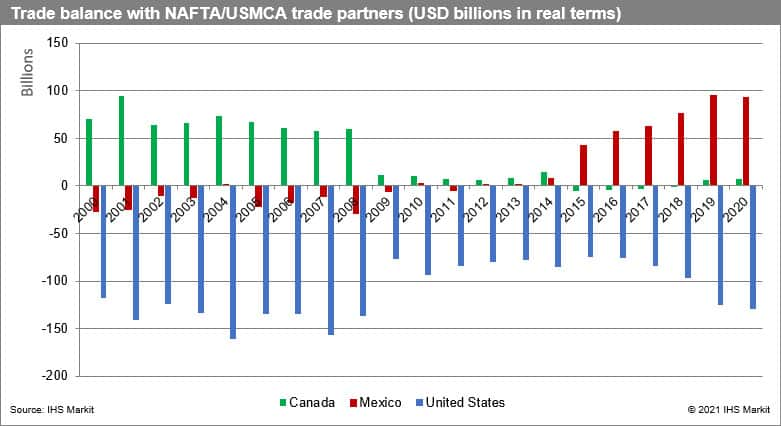

- U.S. has a permanent trade deficit with USMCA partners, while Mexico enjoys a growing surplus from 2012 onwards; Canada also enjoys a surplus

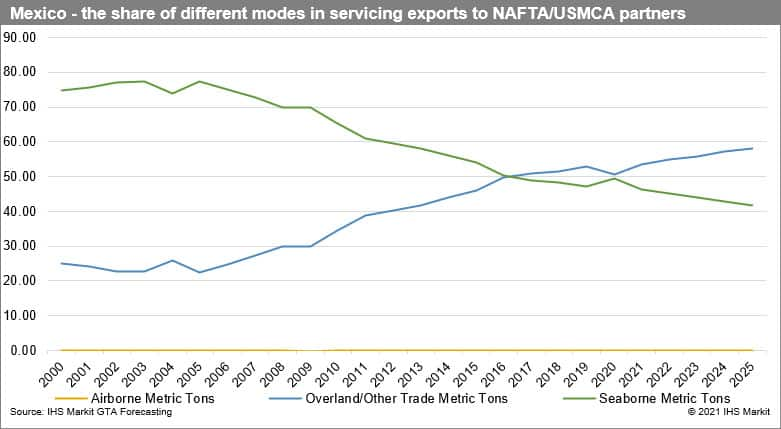

- Economic effects of USMCA are going to be limited, with major effects related to trade liberalization at the initial stages of NAFTA, however, certain sector could be more affected: dairy, steel and aluminum, textiles & apparel, automobiles; USMCA is likely to affect overland transport/logistic modes in particular road and rail

- USMCA is more important to Mexico and Canada than to the U.S.

- The most significant changes vis-à-vis NAFTA

are:

- Higher vehicle and auto parts regional value content requirement

- New labor value content requirement for vehicles

- Stricter rules of origin

- Increased access to the Canadian dairy market

- Trade facilitation measures

- Introduction of stricter IP regulations

- A new sunset clause

- Provision on agreements with non-democratic states and provisions on state-owned enterprises (SOEs)

Introduction

The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) after 26 years of functioning. The agreement took effect on July 1, 2020.

USMCA has global significance. It is larger than EU27 and still greater than the economy of China looking from a global perspective (for 2021-2025 we show the new estimated of IHS Markit) in terms of real GDP. The real GDP of USMCA in 2020 was equal to USD 24.2 trillion (30% of global GDP, it was equal to USD 12.5 trillion in 1994 when NAFTA was established and represented 30.5% of the global economy).

Trade between the U.S., Canada and Mexico

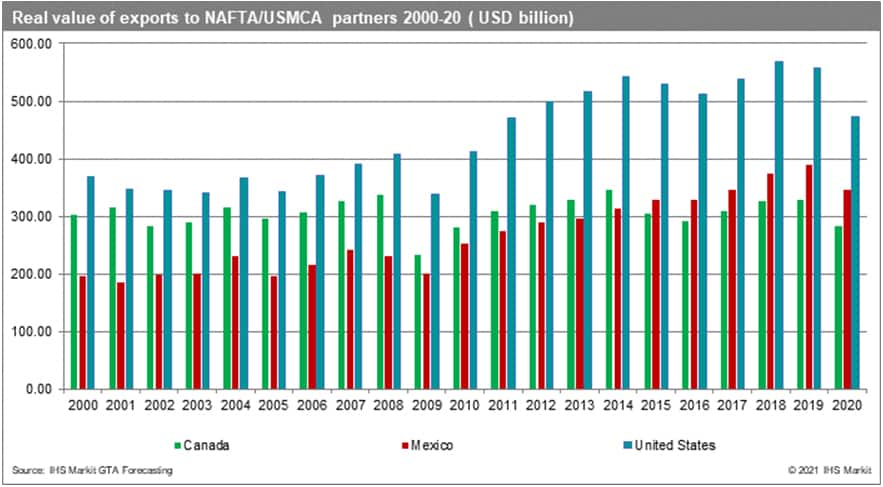

Since the ratification of NAFTA, merchandise trade between the three NAFTA partners increased from around USD 290 billion in 1993 to over USD 1.1 trillion in 2017 in nominal terms (1.2 trillion in real terms in the GTA Forecasting database). It reached 1.27 trillion in 2019 and has fallen to USD 1.1 trillion in 2020 in our estimates.

The exports to other NAFTA (USMCA) partners increased significantly in the case of the U.S. and Mexico throughout 2000-20 the data in GTA Forecasting show. The impact for Canada was limited, with merchandise exports in real terms lower in 2020 than in 2000 (effect of COVID).

If we look at the trade balance data, we see that the U.S. has a permanent trade deficit with NAFTA/USMCA partners, and it has not improved in 2020. Canada is more or less balanced with a small trade surplus, and Mexico enjoys a permanent trade surplus from 2012 onwards (with a slight decline in 2020). The incoming data for 2021 will bring more reliable information - less affected by the specific circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Economic effects of NAFTA

RTAs, such as NAFTA or currently USMCA, create both static effects on trade (classic trade creation, trade diversion, trade deflection, and trade expansion/contraction effects) but also lead to significant long-term dynamic effects. The classic economic literature on regional integration agreements (RIAs) distinguishes free types of allocation effects (impact the static allocation of resources), accumulation effects (impact of the accumulation of factors of production and efficiency and thus growth prospects), and location effects (impact on location decisions of firms). Taking into account the various asymmetries between the U.S., Canada and Mexico in regional and sectoral dimensions and overall level of development, it would be difficult to expect the effects to be symmetric.

In an interesting study published in Review of Economics Studies Caliendo & Parro (2015) estimated a computable general equilibrium model with intermediate goods or input-output linkages & sectoral heterogeneity, to show the welfare and trade effects of NAFTA's tariff reduction. They found that Mexico's welfare increased by 1.31%, U.S.'s welfare increased by 0.08%, and Canada's welfare declined by 0.06%. At the same time, the intra-bloc trade increased by 118% for Mexico, 11% for Canada, and 41% for the U.S. Caliendo & Parro (2015) assert that the inclusion of removal of non-tariff barriers could make the effects, surprisingly small in terms of welfare, larger. In addition, the overall TFP growth rates of the three participating states could have been affected by NAFTA.

As Hufbauer & Schott (2005) pointed in their broad analysis of the impact of NAFTA it was designed to promote economic growth by spurring competition in domestic markets and promoting investment from both domestic and foreign sources. It was successful in this respect, however, the benefits were smaller than expected and rather asymmetric. Thanks to free trade and investments North American firms are now more efficient and productive than priorly, they restructured to take advantage of economies of scale in production and intra-industry specialization. Trade within the block grew faster than with the rest of the world and foreign investments in particular in Mexico soared (in particular by American companies).

NAFTA had a powerful impact on various sectoral production systems in North America redefining how and where products are made, and services provided. Blanchard (2017) studying the impact of GVC calls NAFTA a game-changer. It affected the location of economic activity and sectoral labor concentrations and changed the within-country inter-state flows vis-à-vis cross-border flows. The location effects are larger on the U.S. Mexico border, U.S. trade liberalization happened faster than was the case with U.S. Canada trade relations which had closer ties proceeding NAFTA.

Economists in Canada expected the trade effects to be modest and the changes in trade patterns (inter-provincial trade vs. cross-border trade) to be more gradual. McCallum (1995) and Helliwell (1996) among others, estimated that interprovincial Canadian trade was 20 times as large as trade between provinces and states of equal size and distance, thus proving the significance of the so-called border effect.

Engel and Rogers (1996) found it to play a significant role in borders in determining the volatility of prices and estimated the size of the Canada-United States border to be equivalent to 1,780 miles of distance.

The presence of the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement and the subsequent extension to NAFTA caused a significant change in the pattern of international and regional trade in Canada. Helliwell et al. (1999) found that NAFTA led to a 13 percent reduction in the interprovincial trade in the case of Quebec. Brox (2001) estimated a 6.2 percent reduction in the interprovincial trade share, measured as a percentage of final domestic demand. It implied a decline of nearly one-third in the level of interprovincial trade within Canada in comparison to the pre-NAFTA period. This supports the notion of substantial reconfiguration of production and trade chains. (More detailed analysis of the effects could be found in the subscription version on IHS Markit Connect platform)

Selected provisions of USMCA

USMCA similarly to other FTAs covers a wide range of issues and contains a large set of specific regulations. The agreement copied most of the provisions from NAFTA adding some elements negotiated in the non-ratified TPP.

UMSCA, for many reasons it could be considered as an FTA not leading to further expansion of trade between parties, but as an agreement trying to regulate the trade between the existing partners and eliminate certain objections.

Certain provisions of UMSCA are likely to affect third parties such as China or trade negotiations of the partners of the agreement with third parties or blocks of countries.

Automobiles

Rules of origin (ROO) requirements for the automobile industry order that a certain portion of an automobile's value must come from within the region. In NAFTA, the required portion was 62.5 percent. The USMCA increased the requirement to 75 percent.

There is a concern that the increased domestic sourcing, aimed at promoting U.S. employment, will lead to higher costs of inputs and disruptions to existing North American automobile industry supply chains making it less competitive globally.

Higher costs associated with the introduction of stricter ROOs could raise the price of North American automobiles for U.S. consumers and this could trigger more imports from Asia and Europe.

De Minimis clause

To support greater cross-border trade, the parties agreed to raise de minimis shipment value levels from NAFTA's 7 to UMSCA's 10 percent.

De minimis provision allows a small percentage of outside-of-North America originating inputs that do not meet the applicable tariff shift, to be used in a qualifying USMCA good. A good shall be considered USMCA originating even when it fails to qualify as such under the relevant ROO, as long as the value of all non-originating (thus outside-of-North America) materials used in the production of the goodwill not exceed 10% of transaction value or the total cost of the end product. Therefore, producers may consider the replacement of certain USMCA-originating with non-originating inputs as an alternative to reduce costs and still qualify for preferential treatment. At the same time, they must satisfy all regional content requirements and other applicable regulations, to qualify as originating.

Partners also provided for specific levels of de minimis trade to simplify formal entry procedures making it easier in particular for SMEs to participate in cross-border trade. Canada for instance elongated the date for payment of taxes for importers to 90 days after entry.

Other elements we discuss in the full version of the article in the subscription version on IHS Markit Connect platform. These include:

- Labor market provisions and minimum wages - protection of U.S. jobs

- Larger access to dairy market

- Intellectual Property Rights

- Sunset clause on the elimination of foreign office and local presence requirements

- Dispute Settlement Mechanisms

- Sunset clause for USMCA & the Free Trade Commission

- Currency and macroeconomic stability

- Exchange rate manipulation & market interventions

- Clause 32.10 - negotiations with third countries

- State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs)

Conclusions

As we can see trade liberalization within NAFTA led already to the significant adjustments in trade and economic activity in general within the three states with limited impact on overall welfare. It seems that the overall impact of USMCA will be limited as it's a delicate modification of the original NAFTA agreement supposedly trying to equalize the benefits between parties involved.

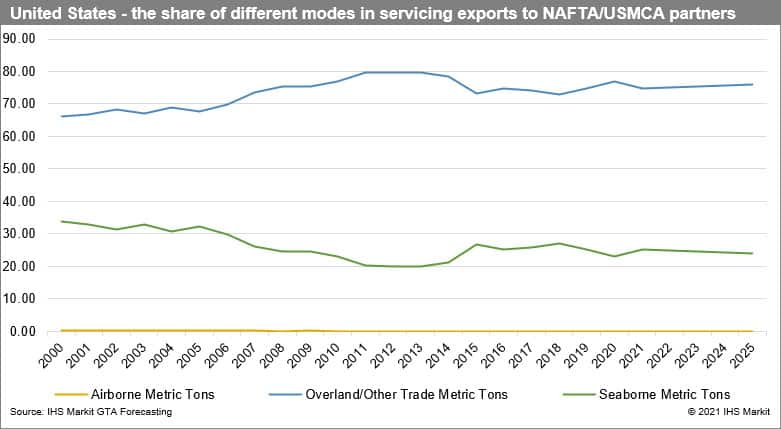

Nonetheless, the impact on particular industries could be significant. These include the dairy sector, steel and aluminum, textile and apparel, and in particular the car industry. In the automobile industry, USMCA could lead to adjustments in the North American production chains and limit its global competitiveness. Overall, more trade is beneficial to logistic & transport industry, in particular road and rail taking into account the tendencies in transport modes in servicing intra-USMCA trade as shown beneath (calculation using GTA forecasting estimates). Interestingly, overland transport took over the role of most significant in Mexican exports to USMCA partners even prior to USMCA taking effect which is mostly due to the shift in product structure of Mexican exports.

With the agreement ratified, uncertainty in trade between parties present in the negotiation phase after the establishment of the Trump administration in the Oval Office was reduced, which should be beneficial to mutual trade relations. Nonetheless, the sunset clause could potentially lead to renegotiation of the terms in the future.

Burfisher et al (2019) in their CGE model showed that the key provisions of USMCA would adversely affect trade in the automotive, textiles, and apparel sectors, while generating modest aggregate gains in terms of welfare, mostly driven by improved goods market access, however, with a negligible effect on real GDP. The welfare benefits from USMCA would be greatly enhanced with the elimination of U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from Canada and Mexico and the elimination of the Canadian and Mexican import surtaxes imposed after the U.S. tariffs were put in place.

Complicated and costly to implement USMCA ROOs may worsen conditions for Mexican producers willing to export duty-free to the U.S. and thus could dampen the Mexican exports. Exporters are, however, likely to adjust fast to the new setting.

The large changes due to trade liberalization have already taken place and only a significant deepening of the agreement could bring substantial adjustments such as the establishment of a common market similar to the EU27 (EEC) framework or Mercosur. This is however unlikely, for obvious reasons. Looking from another perspective, a dramatic change would be the elimination of free trade within North America, but this is even more unlikely even if Trump advocates return to power.

The deal is unlikely to harm EU exports to North America, as the USMCA primarily repeats the prior NAFTA rules. It is worth stressing that the European Union has FTAs with Mexico and Canada which guarantee it preferential access to their consumer markets. The deal could to some effect trade with China, but it is difficult to affect the impact of it. At the same time, the emergence of RCEP could speed up the trade and integration within the Americas - Clinton-era Free Trade Area of the Americas project potentially appearing on the political agenda.

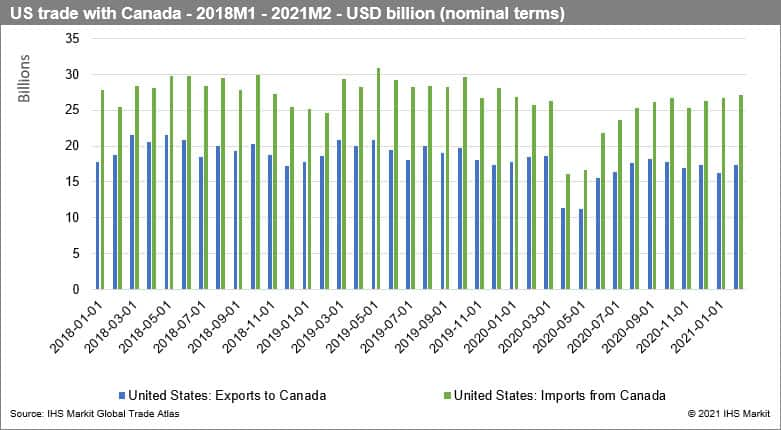

To fully assess the particular effects, we have to accumulate more data from the moment of establishment of USMCA for the effects at the sectoral level to appear. For the time being, the flows are blurred by the impact of COVID. As we can see from the following graphs based on the Global Trade Atlas of IHS Markit the trade between the USMCA parties to a large extent recovered from the pandemic shock reaching pre-pandemic levels.

(The dynamics of monthly trade flows available in the subscription version on IHS Markit Connect platform.)

This column is based on data from IHS Markit Maritime & Trade Global Trade Atlas and GTA Forecasting as well as other resources avialable to IHS Markit clients.

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter and stay up-to-date with our latest analytics

{"items" : [

{"name":"share","enabled":true,"desc":"<strong>Share</strong>","mobdesc":"Share","options":[ {"name":"facebook","url":"https://www.facebook.com/sharer.php?u=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fusmca-an-enhanced-framework-for-trade-within-north-america.html","enabled":true},{"name":"twitter","url":"https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fusmca-an-enhanced-framework-for-trade-within-north-america.html&text=USMCA+-+an+enhanced+framework+for+trade+within+North+America+%7c+S%26P+Global+","enabled":true},{"name":"linkedin","url":"https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fusmca-an-enhanced-framework-for-trade-within-north-america.html","enabled":true},{"name":"email","url":"?subject=USMCA - an enhanced framework for trade within North America | S&P Global &body=http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fusmca-an-enhanced-framework-for-trade-within-north-america.html","enabled":true},{"name":"whatsapp","url":"https://api.whatsapp.com/send?text=USMCA+-+an+enhanced+framework+for+trade+within+North+America+%7c+S%26P+Global+ http%3a%2f%2fssl.ihsmarkit.com%2fmarketintelligence%2fen%2fmi%2fresearch-analysis%2fusmca-an-enhanced-framework-for-trade-within-north-america.html","enabled":true}]}, {"name":"rtt","enabled":true,"mobdesc":"Top"}

]}